Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

I wrapped up the last issue on the note that female fans can act as gender equality trailblazers and embody Zhao Lijian at the same time.

Past incidents that gave rise to the notoriety of female fans being “pinkie” construe them as the Little Red Guards in the digital age. They are spontaneous, hotheaded fanatics (pun intended) robotically upholding party ideology.

But I’m not feeding into the conventional understanding of fanquan’s relationship with nationalism today, because that is no longer the whole picture. The era of bombarding foreign websites to crush (cyberbully) antis against China has ended. This paper on such “fangirl expeditions” during the Hong Kong protests in 2019 is an expansive look over the events, and perceptively notes a change in the fan-state relationship since then.

It is that fangirls cannot be easily instrumentalised by the state to spread its agendas anymore. After the expedition, many fans were astounded by the quick turnaround in official rhetorics that went from celebrating their heroic defence of the CCP, to condemnation and regulation of their “toxic” behaviour. That widespread disillusionment has led to a much more awkward mating dance.

Today, both the celebrity and their fans tiptoe around nationalism with tremendous unease, driven by survival instincts to occasionally flaunt its feathers.

Calculated Alignment

Don’t get me wrong. Fanquan does conform to state discourses.

But the twist is this: nationalism is sought as a means to eliminate opponents more than anything else. As I demonstrated in the last issue, in a competitive context like Produce Camp or just the entertainment industry as a whole, nationalism is a tool wielded out of convenience. Out of necessity.

The same goes for a series like Word of Honour. Fans of the show’s two male leads, Gong Jun and Zhang Zhehan pitted themselves against each other after the show experienced explosive success in 2021, with both sides wanting more exposure and recognition for their celebrities. Their routine fan wars rapidly escalated when old photos of Zhang at a controversial Japanese shrine started to spread.

Gong’s fans sprung to condemn and boycott their competitor’s unacceptable behaviour that, as termed by People’s Daily, “challenges national dignity”. They tailgated, if not propagated waves of public reproach that eventually banished Zhang from the entertainment scene. He’s now forced to use Instagram to communicate with his fans because all of his social media accounts on this side of the wall got banned. The fervour behind the banishment is likely not because Gong’s fans are genuine believers in the party (some of them could be), but because it is a handy little trick, nationalism. Opposition can be speedily removed if you stand on the right side of history.

In other contexts, fans build a nationalist image for their idol (and their fan communities) out of practicality (Wang and Luo, 2022). Welcomed by their fans, the likes of Jackson Yee drift towards the main-melody by reposting the appropriate state-approved content, starring in state-funded blockbusters and securing bianzhi to pander for career longevity in return. Another classic move is performing at CCTV’s annual Spring Festival Gala (春晚), which equates to a stamp of approval from Up There.

It used to be the unequivocal endgame that every celebrity and their fans aspire towards, the most-watched entertainment program in the country. Fans of 春晚 (and AF) regulars like TF Boys and Wang Yibo boast of their attendance, again out of functional reasons. They want the Gala aura as a sign of success, rather than genuinely aligning with the ideology.

This is especially clear after 春晚 became, for the lack of a better word, total shitshows that the nation loathes. It’s tacky visuals, appallingly cringy content and a didactical tone duct-taped into a 4-hour drag of propaganda.

Its declining reputation resulted in fanquan’s cautious steer away from the program that’s almost imperceptible to the eye. Very infrequently, you’d see the fans of a celebrity who’s not on the Gala’s cast list quietly celebrate their absence. No good in being too nationalist, they rightly argue, because at one point the nationalist image can become a pedantic overkill. Idols like Zhang Yixing and Luo Yizhou have indeed been ridiculed because of their too-obvious attempts at pandering. Zhang’s profile picture on Weibo used to be a map of China inclusive of the disputed Senkaku Islands/Diaoyudao Islands, and Luo’s is a headshot of him in military uniform. It will drive fans away because celebrities are ultimately there to be sources of beauty and entertainment, not regurgitators of People’s Daily.

Politically Correct Silence

To strike a balance between conformity and popularity, fans would often urge celebrities (and remind themselves) to tread carefully instead. The result is promoting a general avoidance of political issues as a rule of thumb (Issue 01 covers this in detail). “Political correctness” (政治正确) for Chinese celebrities is pronounced as silence at most times.

The A4 Revolution went by almost undiscussed in fanquan. Few braver celebrities who did express support got their Weibo account temporarily suspended and in more serious cases, their works removed from streaming platforms. Most fans claimed that they deserved it because celebrities “should stay out of politics”. Only a handful of fans stood in solidarity with them and commended their bravery, but even then their respect was only inferred for fear of being attacked by other fans.

Some noted that those accounts were suspended by Weibo due to “violations of laws and regulations” and not the usual “violations of community guidelines”, meaning the suspension could have been a direct order from a law-enforcement entity other than the platform. This is a telling distinction that explains why Chinese celebrities and fans are constantly avoiding politics.

Celebrities and entertainment are seen as parts of the sociocultural sphere that is separate from the political sphere. They should conform to the latter in order to stay strictly in the former. Likewise, fans are happy to defend social issues like gender equality and unreasonable COVID-19 restrictions that led to the revolution (not realizing that they are politicized) but are quick to detach themselves once it nears the mine zones of political rights. That’s not for the masses to talk about. One should stay quiet and obey.

By far the most mind-boggling comment I’ve seen in fanquan debates surrounding A4 is this. A fan wrote on Weibo that A4 makes sense and is what the state deserves to bear after outlawing female fan favourites like xuanxiu and male homoerotic fiction-turned TV shows (dan-gai). You’ve taken away all the “soma”, the drug that lulls people into feigned contentment. And where do we go now? Of course, we turn to politics and be angry at the government. They phrased the post as a petition for authorities to release all the dan-gai that’s been abruptly banned from airing in 2021, and everybody would instantly be happier. 1

This captures the convolution of fandom and politics perfectly. There’s the acknowledgement that entertainment is a pacifier, an anaesthetic and a distraction tactic away from what we really should pay attention to. There’s also self-mockery at how well we can be pacified and suck it all up. There’s a faint recognition that dissatisfaction is legitimate and rebellion is necessary, but there’s also a doubt of its futility.

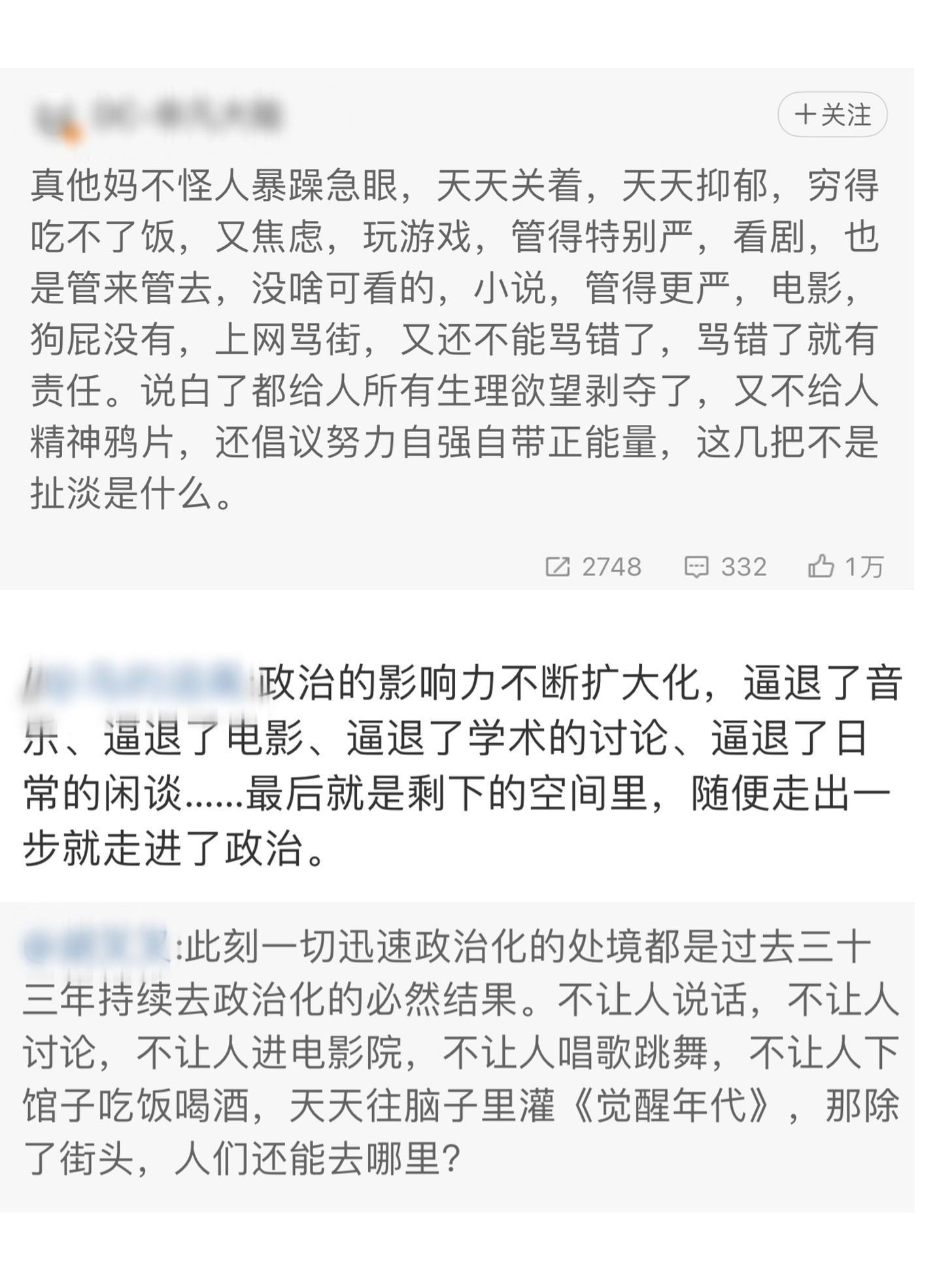

Similar arguments were made in a non-fanquan context. The top post in the image below wrote on the 27th Nov 2022, amidst the A4 revolution:

no f*cking wonder people are angry. [we are] Locked up everyday, depressed and poor to the point of starvation and anxious. Games, TV series, fictions, movies are all tightly controlled, can’t swear and vent on the internet fearing repercussions at the wrong kind of venting…Physical needs are stripped and psychological opium is denied too, and they [dare] talk of ‘positive energy and hard-work’, this is all bullshit.

The bottom post wrote:

The increased politicization nowadays is the inevitable consequence of the depoliticization in the past 33 years [written in 2022, therefore referring to 1989]. Not allowing speech, discussions, movie-going, dancing and singing, eating and drinking in restaurants while piling Awakening Age [editor’s note: propaganda drama] into our heads, where are people supposed to go if not to the streets?

Retweet wrote:

The influence of politics is expanding, forcing music, films, academic discussions and daily conversations to stand down…At last in the remaining spaces we have, any step outward is a step into politics. 2

Who’s The Real Anti?

Besides these intricacies, portions of fanquan simply refuse to be nationalistic. They outright reject mindfulness of their national identity or their “obligation” to protect the country as a fan. This stems from the disillusionment not just from the expeditions I mentioned earlier but more recent events like the Dior skirt controversy.

Despite people’s widespread anger at the brand’s cultural appropriation, state media responded belatedly and perfunctorily to the incident which led to confusion as to why China is underreacting.

This was cited again in the lunar new year controversy two months ago. Usually quick to condemn, boycott and cancel the China antis, fans are defying that habit altogether. Why bother, they argue, when the government seems to take no heed of it? Feeling used, exhausted and betrayed, they don’t want to dirty their hands with nationalistic advocacy on CCP’s behalf anymore.

Mixed in with this bunch are genuine political dissenters and fans of artists who want to defend the celebrities’ supposedly anti-China (辱华, pronounced ruhua and shortened as rh) behaviours. Fans of Zhang Zhehan actually “martyrised” him as a victim of pinkie (and by association, state power)’s assault, which in effect resembles a sort of resistance to the party. Subtleties in positions might vary, but on the surface, these people are standing behind one banner: why should “rh” get in my way of being a fan?

I started to notice the prevalence of this attitude when I returned to K-Pop after experiencing emotional trauma from Produce Camp and mainland entertainment. Most K-Pop fans are much more desensitised to ruhua. Ever since THAAD and the Korea-Ban (禁韩令), Chinese K-Pop fans have felt like they are cornered by a political exigency to un-fan. They are sick of being policed by nationalists who intervene in their leisure activities, constantly wanting the liberty of self-indulgence and to regain agency in fanning foreign artists. They are drained from pressures to take the moral high ground and compensate for the fact that their idols are non-conforming.

They are turned into oblivious radicals.

As countered by a K-Pop fan when they are accused of liking ruhua artists, the government itself is the “biggest anti” of China. 3

The Economist’s commentary on China’s post-Two Sessions political strategy mentioned the state’s increasing concern over “external threat”. Vocabularies like “security” and “self-reliance” pervade the official documents.

In the two succeeding issues, let’s talk about that external-internal tension in the fandom context. How is K-Pop playing out in China? How are Western celebrities received online? What are the ongoing cultural clashes in the entertainment world and how are fans dealing with them?

See you then! 4

Original post untraceable. Again I’m sorry, you’ll have to take my word for it.

Translation by me.

Original post untraceable. See similar posts below. Translation by me.

"They phrased the post as a petition for authorities to release all the dan-gai that’s been abruptly banned from airing in 2021"

The funny thing about this is, from the danmei I've read (in translation; a decent number but not everything that's there, admittedly) law enforcement, however that looks in the world of the novel, is often central to the narrative. Surveillance is panopticon level; the copaganda sounds sincere and not even a little satirical - if the NRTA or whoever had any sense, they'd release all the dangai, because the authors are often fully and perhaps strategically on the side of the state.