Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

We saw how a celebrity can bleed intimately into the fans’ personal lives in the last issue. Offline fan events and practices like concerts and birthday cafes ground the fan identity in their everyday experiences. Today, let’s talk about fan service and “reverse support” (逆应援): what are the various acts committed by the celebrity to specifically cater to their fanbase, and why is that significant? In other words, how are they actively encroaching on the fan’s everyday experience and why?

Supply and Demand

This is a clip taken from ‘CARATLAND’, a stadium-wide fan meeting of the K-Pop group SEVENTEEN. The members are in the middle of a legendary segment called ‘unfit songs’, where they perform stages chosen by fans that supposedly don’t suit their usual image. Here, the tallest, most “macho” gym rat and rapper of the group MINGYU is dancing to a particularly cutesy girl-group bop adhering to fan requests. The same segment featured usually “feminine” presenting members like JEONGHAN rocking to Hip-Hop tracks and rapping.

That’s probably why ‘CARATLAND’ is in ridiculously high demand every year, because it is essentially a ‘fan service’ show. It places fan requests at the very heart of its pageantry.

One of the newer additions to fandom vernacular, ‘fan service’ describes anything the celebrity does to meet a fan’s need. It could be doing dance or song covers that fans want to see, wearing a certain outfit, changing a part of their appearance like getting a haircut or doing certain poses for the camera. Ironically, fans get the most say on the peripheral fixtures of an idol’s persona. The crux of their job - performances, discography, and career trajectories are mostly out of reach. Everything else can be interactive nowadays: fans throw a penny to make a wish in the fountain that is their fan club forums or livestream comments, and idols react to grant it. I cannot stress this enough - the modern-day idol presence is co-authored by the fans.

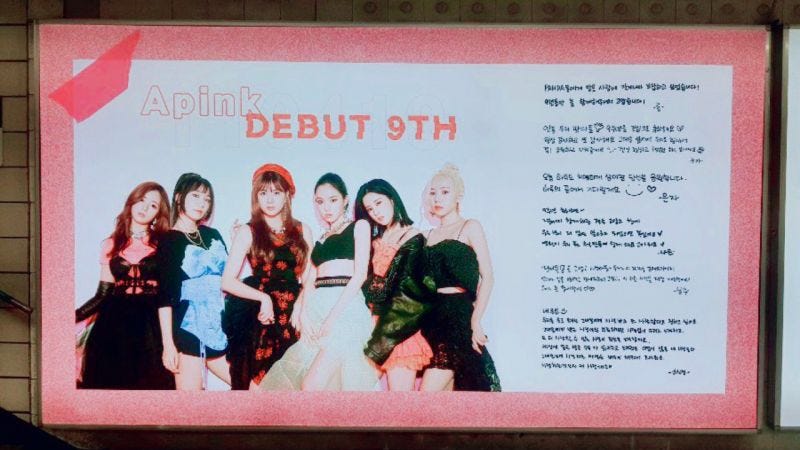

Most fan services are virtual and immaterial but with some exceptions. Originally a K-Pop phenomenon, 逆应援 specifically refers to idols returning the favour of their fans by doing traditional fan support in reverse. They can buy out subway adverts on debut anniversaries with appreciative messages, or give away merch items on specific occasions.

A lot of 逆应援 is food-related and that’s how it started: handing out bento boxes, hot beverages or snacks to fans waiting outside a venue for an extended period of time. In recent years, there have been increasingly more efforts invested into these projects, spurring an unspoken contest between idols as to who’s more dedicated. What started out as relief packages and small tokens of appreciation evolved into loaded performances of gratitude. Tomorrow X Together’s SOOBIN, in his latest comeback, rented out a bakery, pulled an all-nighter and hand-baked hundreds of cookies for music show attendees. Personally prepared messages were part of the package, with heartfelt expressions of love for their continual support.

Although less of a custom in neiyu, Chinese celebrities are starting to emulate it, be it buying pizza, coffee or cakes for their fan bases. Liu Yuxin’s idol teammate, Yu Shuxin, is known for her “fan-spoiling” (宠粉) behaviours, who’s now venturing beyond foods and giving out high-end perfumes as well as COVID-19 supplies like masks. The actor Chen Zheyuan gave out single roses and ice packs to the fans he met at an outdoor event in August. Likewise in the K-Pop world, female soloists like Hyun-A or JENNIE from BLACKPINK have been giving out makeup products or clothing items.

The transition from perishable, consummable treats to valuable gifts is noteworthy. It has transformed the intent behind the reverse-support culture from showing reciprocation to seeking approval, or even impressing and pandering. Some criticise these as publicity or marketing stunts, and it is indeed so in some instances. Many giveaways consist of products the celebrities themselves endorses, making the gesture a poorly disguised brand promotion and an opportunism-driven chore. Sometimes it could barely pass as a 逆应援: when neiyu boy-group TNT was promoting KFC, their merch giveaways were contingent upon the purchase of branded items that they endorse. You get to procure these “fan benefits” (粉丝福利) but only after you’ve paid a price and with that, validated your fan credentials through expenditure.

Here comes the ultimate question overshadowing reverse-support culture and, more broadly speaking, all acts of fan service: who deserves to be serviced?

Going Offline

The terminology of “fan service” has a deceiving aura of encompassing all fans as its targeted audience. This is a partial truth. For virtual and immaterial fan service like composing a “fan song”, it carries a universal message of affection.

But the nature of 逆应援 predetermines that it is a reward for those attending offline events. This mirrors a wider tendency in fandom to celebrate offline practices and fans who act upon their fan identity in real life. In case it wasn’t clear from previous issues of this publication: yes, fandom is incredibly hierarchical. “Going offline” (追线下) is a badge of honour that showcases the length one’s willing to go to as a supporter.

Fanning offline connotes differently to attending large-scale and (relatively) accessible events like a concert. I can’t cite any sources to explain the subtlety of this difference with it only being a conversational undertone. There’s a built-in exclusivity to “追线下”: it is a noble act reserved for a privileged few, for which they will receive rewards in accordance to their labour.

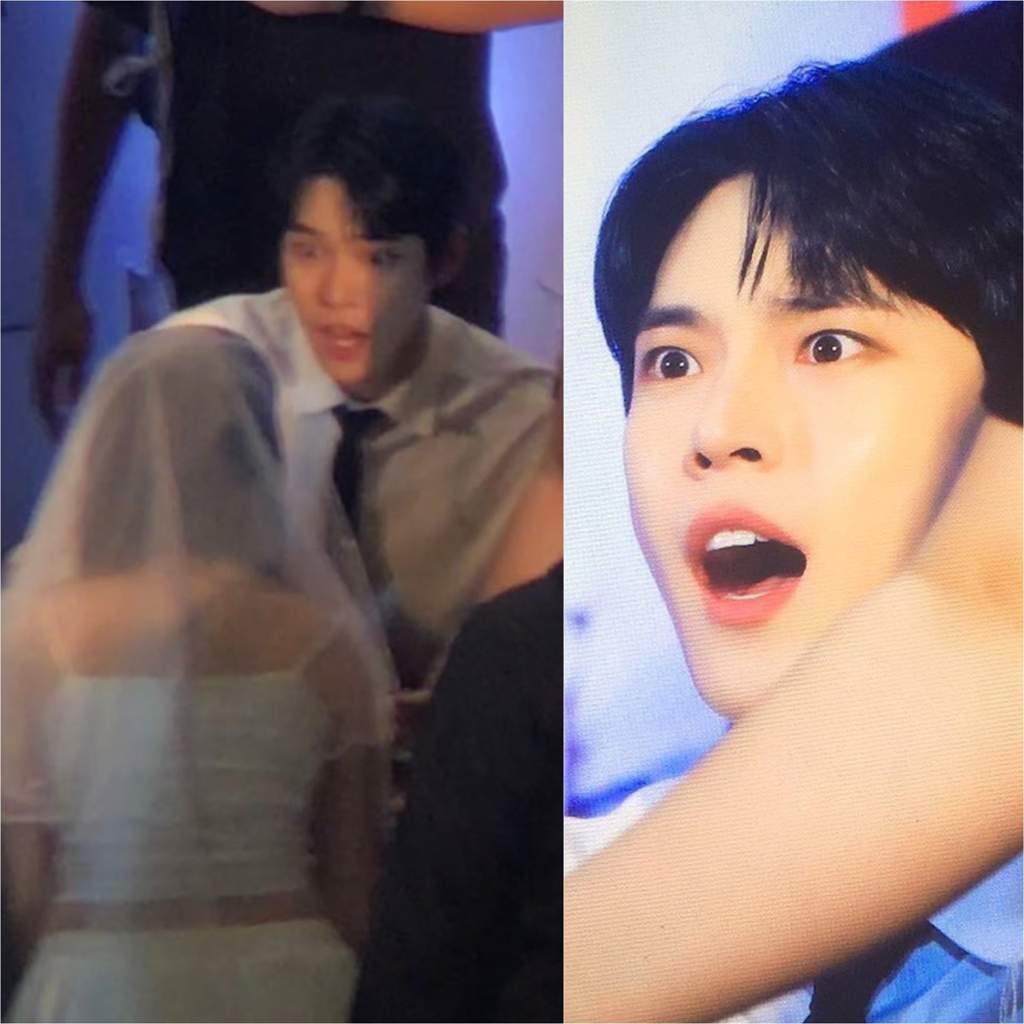

“Labour” in this context is physical as much as financial. I’ve mentioned before how in order to be eligible for a fan sign, people often have to splurge a fortune. In return, they’d get to meet the idols up close, sometimes disturbingly so. Romantically interlocking fingers is of the norm now. I’m seeing bicep pats, dimple-poking, face squishing and so on. People bring wedding veils and rings either for the idols to wear, or for the idols to put on them. They prepare pick-up lines to confess to the idols, or “trick” them into a confession to themselves. Dress-ups, mini roleplays, you name it - fans are mainly just having fun, but also constructing prepped scenarios at fan signs to briefly realise an illusive intimacy.

Don’t get me wrong, fan signs and fan calls etiquettes are not hot-off-the-press debates within fandom. Sexual politics and power dynamics revealed in these fan-idol interactions are frequently mulled over. One camp argues that celebrities are not pets and playthings at the fan’s disposal, whereas others claim the legitimacy of getting “serviced” after they paid a hefty amount for it. An associated topic of contention is whether one should position the celebrity as the victim or the perpetrator. Are they obeying fan instructions under implicit coercion or are they fuelling fantasies to further exploit the fans for their money?

And then there’s the question of ownership. Fan-idol relationships are fundamentally polyamourous. When those intimate moments are posted online for the wider fandom to see, is there a discomfort that stems from being a voyeur and an intruder? Are we all torn between feeling satisfied and betrayed? Additionally, we’re essentially pirating films we didn’t pay for. Should we pay to see it?

To further complicate things, there are also heartwarming moments where fan service consists of “platonic” emotional support. People read out lengthy letters at fan signs about their personal struggles and receive consolations as well as encouragements. Is fandom substituting themselves in the place of the lucky fan to be indirectly consoled?

Just to throw in even more open-ended questions, I need to bring up fan service that involves a “sell of rottenness” (卖腐), where the celebrities feign homosexual intimacy to attract shipper fans and their investment. The verb choice here is revealing enough. Fans pay for the intimacy they consume, but who is the more powerful here? Who is “at fault” here?

Boundaries

In the last issue, I talked about how fan practices can become more and more untethered from the celebrities themselves as it becomes more spatialised and situated. In a way, the further meaning-making goes astray from its subject, the more omnipresent the subject becomes. You’d see your idol everywhere if you make it so.

Fan service is the other side of the same coin. Whether they want to or not, idols are inching closer and closer to you until their presence becomes everywhere in your reality. As I mentioned before, celebrities are starting to show up physically at offline fan events or even private occasions, with prominent examples like IU attending a fan’s graduation ceremony (and buying gifts for the entire auditorium). Yu Shuxin, when giving out a specific kind of pastry to her fans, said that she thought about them when eating it herself and wanted to share the joy like she would with a friend.

These parasocial relationships get problematic when boundaries become blurred. Earlier this year, former K-Pop idol Jackson Wang hosted an after-party to his concert in LA that openly advertises an “intimate experience” with him. I personally found the wording of the event description extremely disconcerting:

This is a rare opportunity to get up close and personal with one of the most talented and charismatic performers in the music industry today. The Academy is a boutique venue that offers an exclusive, VIP experience for a limited number of guests.

So if you’re looking for an unforgettable night of music, dancing, and pure fun with one of the hottest stars in the game, then you won’t want to miss [the party].

This kind of event would be condemnable as a potential 私联, meaning an inappropriately close relationship with a fan that is one of the most unforgivable trespasses of an idol. But in this example, who’s being exploited as assets here? The artist who’s branded like an attractive commodity or the fans who are about to pay for it?