Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Earlier this month, I was persuaded (read: coerced) by my best friend to attend her favourite Chinese idol’s concert with her. Fresh out of the mountains (to see what I meant by this and why I haven’t been updating, read my Notes here) and in dire need of a topic to write about for the next issue, I packed a Kanken bag and hopped on a gaotie with her to spend 27 hours in Shanghai.

Here’s what happened.

My best friend (hereafter known as W) immediately spotted a fellow fan seated a few rows in front of us when we boarded the train from Beijing. When I asked why, W explained in detail how their phone case seemed to be in the official fan support colour (应援色) of the idol, a specific shade of teal. She also carried a Christian Dior handbag and wore a specific bucket hat, both pieces from brands that the idol endorsed.

Later, I would see for myself at the venue that Chinese idol fans, when attending offline events like concerts, would all choose to dress deliberately subtle but identifiable to a pair of knowing eyes. It’s a fun little exchange, a silent and elegant in-joke relished in public. This is evidence that celebrity-related items in every sense (sponsored products as well as fan-made or official merch) are seen as highly symbolic tokens with emotional value. Putting together concert outfits with these tokens is a critical ritual to engage with the celebrity, their fan community, and their own experience as a fan.

I marvelled at such a coincidence and W responded to my surprise nonchalantly: she had already seen a couple of them in the station, taking different trains and flocking from the capital to where the tour takes place. When we arrived at our hotel located within walking distance of the venue, we saw fans exiting rooms neighbouring ours. We didn’t know how to get to the venue and we didn’t need to: we simply followed a group of young women on the street dressed identically in teal-coloured t-shirts.

From my descriptions so far, you might assume the idol is a man. After all, Chinese male idols in general have a much larger and more devoted following due to the overwhelming number of female neiyu fans. But, W is one of many “umbrellas” (fandom name) who are fanning Liu Yuxin, an idol who identifies herself as a woman, but presents as someone much more nuanced than that.

Arriving at the venue, I saw a fan-made sign that said “中女一”, “China Female One”, an abbreviated version of “China’s Number One Female Idol”. It’s not that much of an overstatement as her Weibo follower stands at 24 million. Liu is a Kiwi School idol, emerging out of xuanxiu in 2020 as the undisputed “ace”, meaning an all-rounder. I had previously seen her performances and reality show appearances, thanks to W’s persistent lobbying. I kept an eye out for her from the sidelines, in a way not unlike how you would keep track of a best friend’s partner’s life events. I knew Liu is a confident dancer and an authentic but reserved individual, almost too stoically quiet to stand out in the industry. From W’s crash course on the train, I learnt that Liu’s career follows an all-too-familiar trajectory of the “underdog heroine”. Small town prodigy, humble beginnings, hard-work paying off, the usual.

What makes Liu stand out eventually is something else entirely. I realised, as she ascended onto the stage, that she might be China’s first and most influential openly gender-fluid idol.

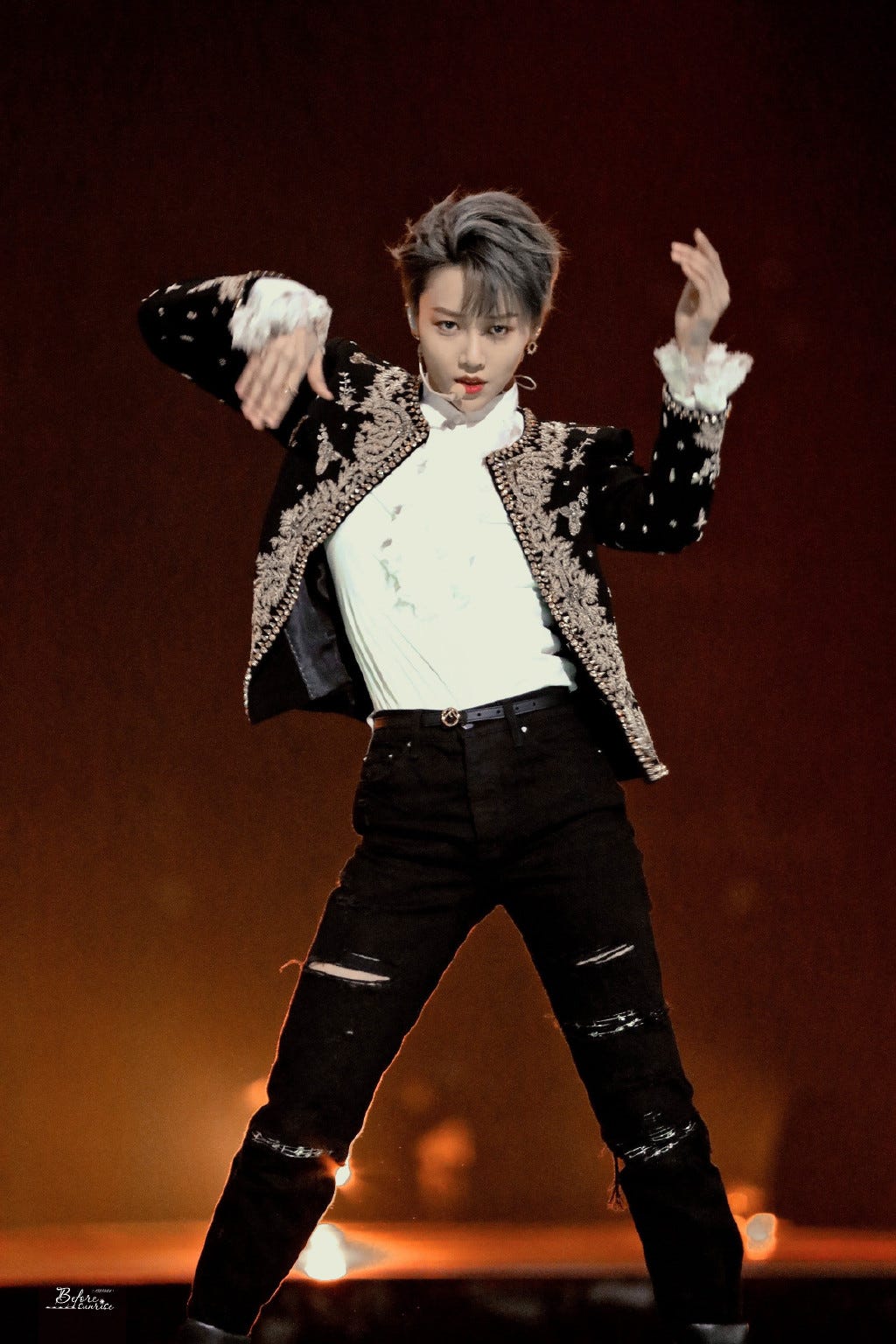

Ever since her xuanxiu era, Liu had always sported this boyish haircut and an androgynous style (unlike previously mentioned male idol Hu Yetao, who changed his image halfway through xuanxiu). Her Hip-Hop dancer background led to stages that are distinctly “macho”, and music that is much less about the tunes than the choreo. Her discography is made to complement and flatter her dancing abilities. It is characterised by heavy EDM beats, long verses of bilingual rap, and a lot of instrumentals, all elements stereotypically regarded as masculine.

Her outfits were consistently androgynous throughout the 2-hour show, including faux-fur robes, an army-uniform-ish buttoned suit, pyjama sets, and tank tops with high necklines but cropped midriffs. She also covered her hair with a headscarf for the first quarter of the concert and had makeup that made her face look sharper, and more defined. For a male idol to appear feminine is not new, but it is not nearly as transgressive as a female idol becoming (and choosing to stay) ‘manly’. Look no further than Chris Lee (Li Yuchun) to see the dangers of that.

In between the performances, I heard all kinds of screams from both men and women in the crowd. When Liu danced a particularly provocative move, both guys and girls whistled. At one point, a male fan next to us shouted, from the top of his lungs, a sentence that stunned me: “MUM LOVES YOU, WIFEY!”

W told me that this seemingly contradictory statement is the norm amongst umbrellas. You can see Liu as your mum, your daughter, your sister or brother, your wife and your husband, or any combination of these at the same time. Because of Liu’s ambiguous image, she has a fan base that puts themselves in multiple and messily intersecting gender and sexual positionings when they fan. No other neiyu idol has achieved this to such an extent to my knowledge. She has also attracted a fair amount of queer fans: I saw both gay and lesbian couples holding hands inside the venue.

Fascinatingly, W also revealed that the heavy lifters within the fandom tend to be middle-aged women who see themselves as mum fans. By that, I mean major “investors”, the data fans and the lead fans within the community. The demographic of umbrellas is so multifarious I wouldn’t be able to guess half of them are die-hard followers once we walk out the stage doors. Compared to K-Pop, the age range is much wider.

There were office white collars in blouses, heels and hold-all totes. There were actual mums with their children. There were pre-teens, teens and university students, decked out in tutus, dungarees and cocktail party dresses all in teal. We sat behind a couple in their mid-40s, the husband as emotionally remote from the surroundings as me but kept dotingly recording his wife having the best time of her life. It was a beautiful moment of unity when everyone sang along to Liu’s gender-neutral lyrics devoid of all gender pronouns, simply basking in the sounds and energy around us.

It is obvious that Liu knew who she was appealing to, and I’m not sure if the spectrum of sexual orientation suffices as a framework to talk about her intended audience. Naming her tour “XANADU” meaning “an idyllic place”, Liu remarked that she envisages her ideal world as somewhere “diverse and inclusive” (多元和包容的). Her choreographies featured complex interactions with her backup dancers, where women were grinding and twerking on her, while men pretended to choke her.

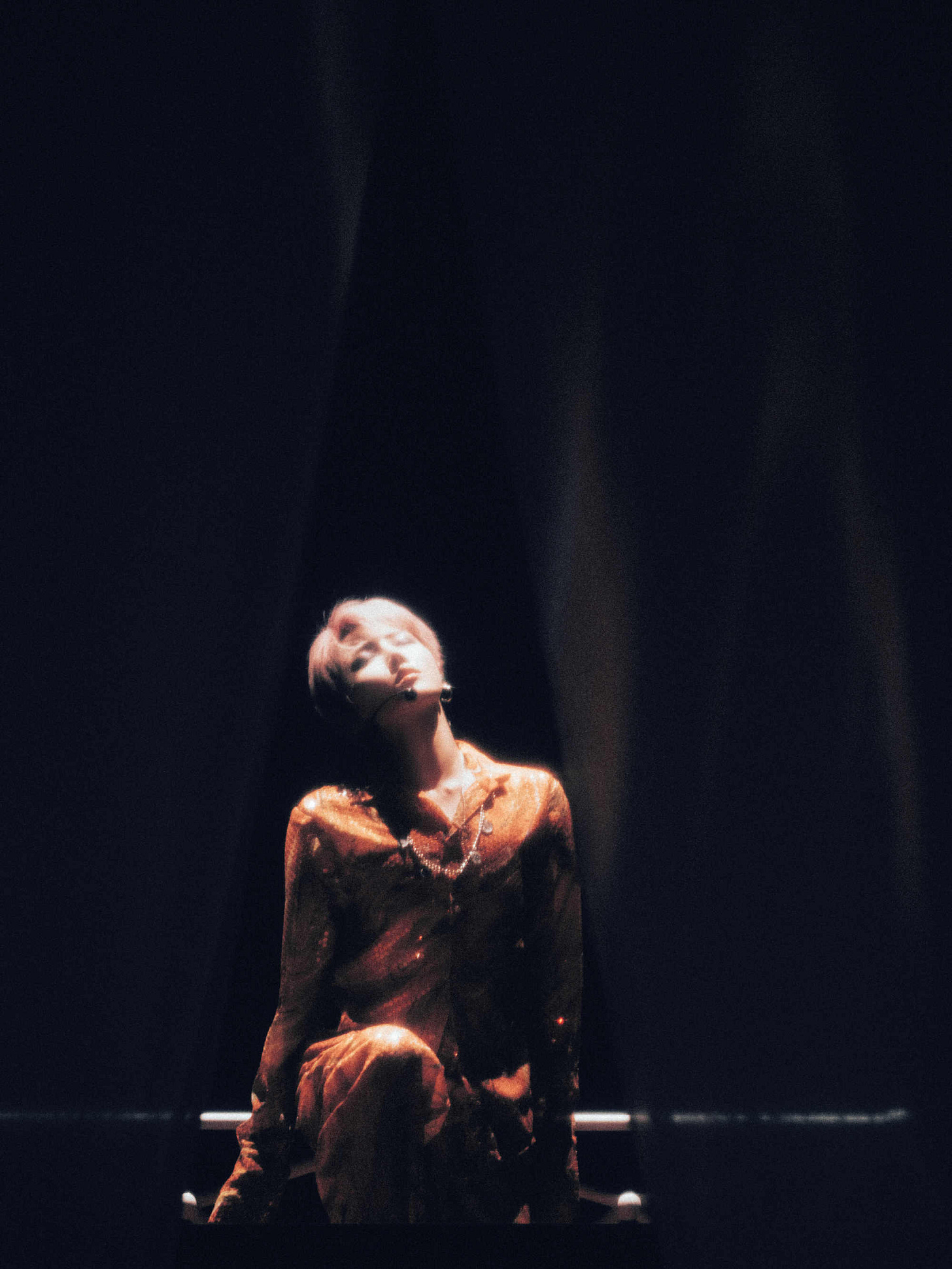

The conceptual video clip that caused the most uproar, was, again, completely gender-neutral. In fact, it was more sensual than sexual, showing Liu crawling on an empty bed with crumpled-up bedsheets, wearing a choker and an oversized shirt. It’s entirely filmed in slow motion, a montage of indicative close-ups of curtains being blown away, chains, hand veins and the like.

Both the subject and the object of desire are missing: there’s no lover, and Liu doesn’t appear to be making love to anything. But fans still went “feral”. I am once again reminded of Katherine Dee’s piece on erotic desensitisation.

We’re so oversaturated with traditionally erotic stimuli that for some people, we’ve effectively desexualised the sexual, and are now sublimating our libidos into anything but sex itself.

She writes that signifiers like curtains and chains can now just be “individual pieces in the ‘Lego set’ of one’s identity, divorced from the context of a relationship, a scene, or even desire itself.”

This is the song performed after the clip, entitled “of course”:

Whether Liu intended to or not, she has successfully exploited our desensitisation. The video partakes in a much more ambitious, and perhaps even deliberately transformatory agenda of un-sexing fandom. The statement is that she won’t just appeal to men or women, gays or heteros. She has elevated her androgyny to cater towards far beyond bisexuality, but the Id of human psyche, the instinctual part of the mind that contains sexual drives. You don’t have to have yourself figured out to enjoy my show, she says, because I only serve signifiers as your dopamine hits, a vague arousal rather than sexed fantasies.

It is difficult to determine how much of it is a conscious moral decision or a marketing stunt, but I want to say both. Fan reactions have always been complicated, W said, as we cycled to our hotel on Meituan bikes. Some are feminist and LGBTQ activists, using her image to turn Liu into a liberal “anti-tradition” icon (反传统先锋). Her song with the lyric “love is love” was labelled a gay rights awareness-raising anthem, while others strongly contested this move out of fear that Liu would be censored, or simply rejecting the “overinterpretation” of an “innocent phrase”. Some report the xin-lefties (those who want Liu to “top” them) and their sexual fantasies as inappropriate and insulting, which xin-lefties see as homophobic. Setting these differences aside, discussions regarding sexuality and gender amongst the umbrellas are rife and disruptive. W told me that their super-topic is filled with dialogues on social genders, the male gaze, being non-binary and queerness.

I had a lot of other questions typed out in my Notes app: some of her backup dancers had dark skin. Where are they from? There was music that sounded tribal. What was that for? She said she’s proud of her ethnic minority roots and used traditional clothing for her dancers. How is she balancing these racial, ethnic, sexual and cultural coexistences?

We stopped at a red light and I thought out loud. W gawked at me in disbelief. “I did not notice any of this”, she said with a broken voice from screaming too loudly, “what were you doing there, essaying?”

She then turned back to the streets ahead of us in utter defeat and smiled a knowing smile: “I knew it. You just can’t turn off your brain.”

Next month, we’ll look at more offline fan events and rituals like concerts, birthday cafes and merch swaps. What happens to the fan-idol relationship and the dynamics within the fandom when such a real-life occurrence takes place?

See you then!