Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

I jotted down a concert experience in the last issue, citing concert outfit design as a key ritual in fandom to engage with the celebrity, fellow fans and their own identities. This issue will focus on a plethora of other habitual practices adopted by celebrity fans to achieve the same end. What follows is a vignette of the life of the parish when God is inevitably out of reach.

No LED? Not a Problem

Concerts are so much more than shows these days. It’s reached pilgrimage status: people travel from afar to witness greatness and attire themselves in anticipation. Compared to sports fans or international celebrity fans, Chinese celebrity fans tend to dress more discretely but still identifiable within their fandom, using celebrity-endorsed items, official merch or support colour as a roundabout way of expression. I rarely see clothing that screams their fan persona, like shirts with the celebrity’s face or name on them. I suspect that’s partly due to the negative connotation of the “fangirl” label I’ve explained before.

That doesn’t mean they won’t assert their fan influence in other ways. More and more elaborate fan projects have been carried out at concerts, most of which are preceded by a month-long preparation process to surprise the artist and profess their love. Early day 线下应援 (offline fan support) involves spectacles staged by LED signs (灯牌). After a nationwide ban of such devices (and bulky items in general) in concerts out of safety concerns, fans resort to other means. At Liu Yuxin’s show, “umbrellas” seated in a specific area most visible to the artist organised themselves to spell out “XIN” using their phone screens.

For projects like these, normally the lead fans in the super-topic would take the initiative, post a “recruitment” advert and rally together other dedicated members. A group chat would be created to sort out the logistics and extensive online communication would ensue in the lead-up to the concert. On the day of the event, they would gather somewhere and rehearse hours before the door opens to ensure a smooth running. This is what I meant when I wrote that fanquan probably houses the closest thing we can get to large-scale civic mobilisation in China.

Territories

Another important function of a concert is its provision of a physical communal space. Fans could be extremely intimate 网友 (internet friends) with each other for years, before properly meeting at a concert for the first time. A recently popularized tradition is the exchange of “freebies” outside the venue, where fan-made merch is given to other fellow fans for free. These can include 手幅 (beautifully designed and printed hand-held signs), photocards, posters, keyrings etc. They can also include snacks and drinks, compiled into a mini ration package to help each other cope with the long queues at the merch stalls or for entrance.

In neiyu, most of these freebies are not given away freely even though they’re free: some kind of proof of the fan identity needs to be shown. It can be your credentials in the super-topic and more specifically your ranking (超话等级), which correlates to your level of activity and your engagement with others in the super-topic. It can be a record of purchase of the celebrity’s magazine, album or endorsed products, sometimes even above a certain figure. Although my friend is a dedicated follower of Liu Yuxin, her inactivity in the super-topic and rational spending history would have denied her many freebies if we were to collect them at the concert. She would have been dubbed a fake fan.

We arrived too late for the freebies anyway. People wrapped up their giveaways very early on adhering to the encouragement of lead fans for all attendees to be in their seats at 5pm, even though the show won’t start for another two hours. This is done in fear of antis taking photos of empty seats and spreading rumours that Liu’s concert is a flop. I am not sure why would an anti pay for a ticket in the first place.

These projects, attiring, interactions, exclusions and strategic maneuvres are all efforts of spatialised meaning-making. A concert is a legitimate territory where desire can be articulated and identity can be validated. To protect the sanctity of such a place is to protect a portion of one’s selfhood.

Situations

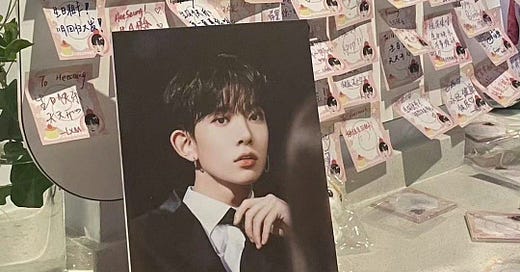

In K-Pop and increasingly in neiyu, “birthday cafes” gain traction as a similar project. In celebration of an idol’s birthday, a venue will be rented out, decorated and managed by the lead fans to host others on this joyous occasion for a meet-up. The community comes together to chat, exchange more freebies and collectively fan their idol. Y/N, the book I mention way too often in this publication has a poignant excerpt on such an offline meet-up at a cafe. Here’s a highlight:

When I arrived, I balked at the threshold, sensing the presence of others like me. There was, slicing a clean line through the bloated cheer, a hostile energy that could be produced only by abnormal love for Moon. I wasn’t sure how to navigate a space filled with strangers who knew I loved what they loved. It was like going to the sauna, except our naked bodies were identical, which made the embarrassment recursive and pointless.

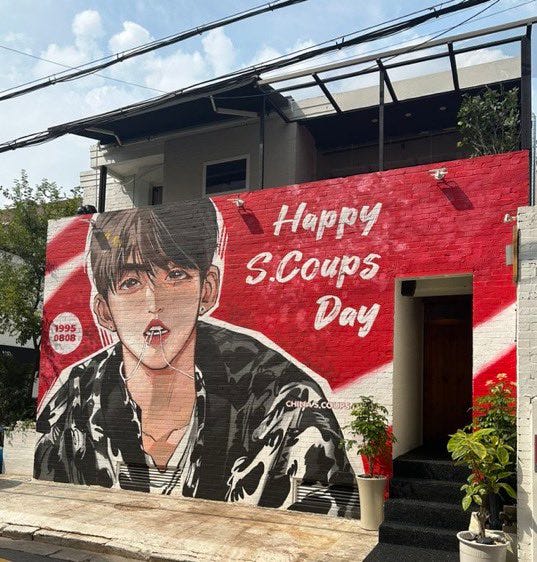

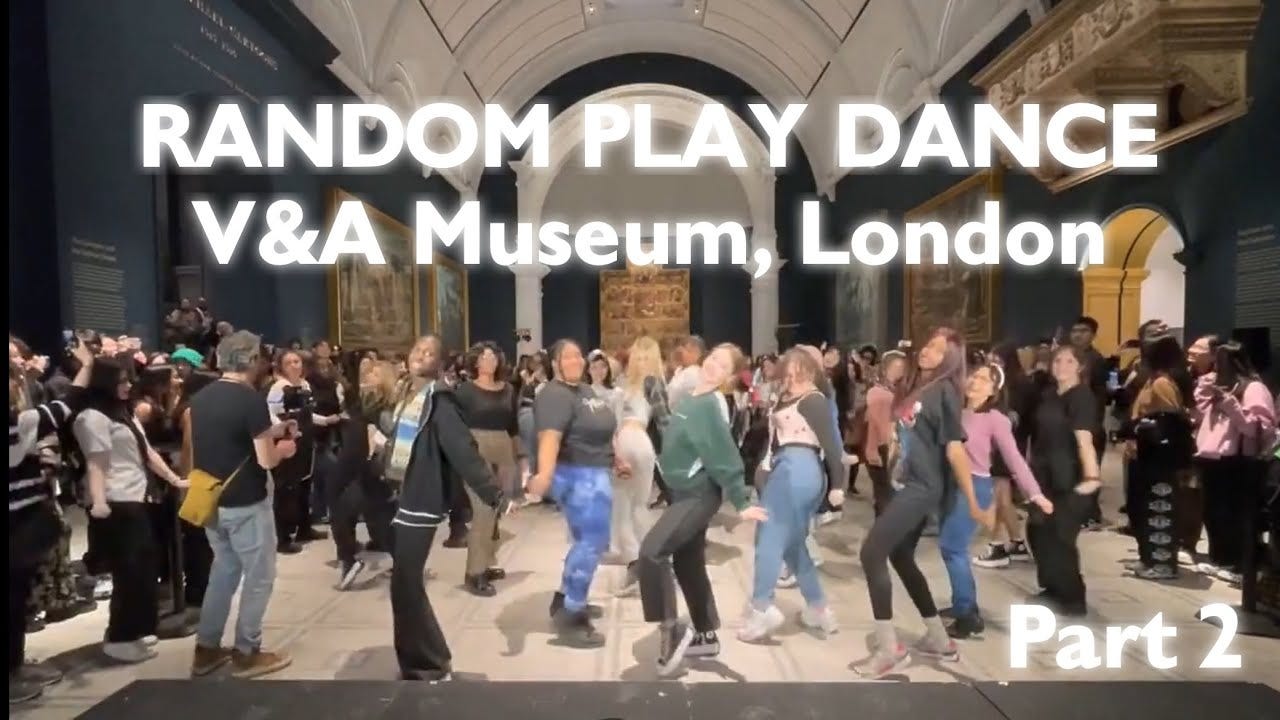

A lot can be done about a celebrity’s birthday. Fans have bought subway adverts, built pop-ups and painted murals, all of which acts to materialise a virtual connection using physical landscapes. Among K-Pop fans, public dancing events at a city’s main attractions are immensely popular. Taking inspiration from “random play dance”, a reality show segment in SK, these events would play snippets of idol songs at random and those in the crowd can join if they know the choreography. Again, fans get to mingle with each other at these sites.

There’s a seemingly unlikely parallel between these acts and situationist thinking. To combat the mediation of relations through images and spectacles, situationists in the 50s-70s used to create “situations” where humans would interact together as people, be fully present in moments of life and pursue authentic desires. A critical difference would be that situationist, with its Marxist roots, contests with commodification and consumerism, the very backbone of some offline fan practices and current celebrity fandom as a whole.

It becomes impossible to document these “situation-creating” when fans visit restaurants celebrities have been to, cities they travelled in. Nowadays, an emerging trend is to go about one’s daily life carrying photocards or plushies modeled after their idols as companions. We can see how astray this is from concerts. Meaning-making becomes more and more untethered from the celebrities themselves as it becomes spatialized and situated.

Like the eternal search for the real I’ve talked about, there’s a constant need to act in fandom that is, perhaps, a direct coping mechanism of said search. Spatialized meaning-making is induced by unease. The unease of existing in a cavity of the half-real, where God is never here nor there.

What I did not expect to see is how idols are beginning to show up at birthday cafes, or random play dances (like HOSHI in the following video at Newark, dancing to his own song with K-Pop enthusiasts) for an impromptu fan meeting. It is a breach of that cavity, a disruption of a real-life situation. I wonder what that would feel like.

*Cover Image: ENHYPEN member Lee Heesung’s birthday cafe in Wuhan and his fans’ handwritten messages to him.