07. The Race

formula 1 fandom, a Class Image, who's the fake fan?, stay-ffic, national pride, and complacency

Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

In the three years of running this publication, I’ve only loved one thing more than I love writing about fandom: learning about a new fandom. I almost savour the way I let my intuition burst through fields of untraversed terrain and guide me towards new sites of fan consumption, fan practices, and fan fervour. I lean into the pull towards wherever people begin to gather, gawk, and whisper, until those voices snowball into a storm.

Standing in the middle of London’s Formula 1 Fan Zone, I felt exactly that.

Let me tell you why.

Disclaimer: The last car-related content I had a genuine interest in was Cars, at the grand age of 8. I had no intention to dive into F1 until a friend (the one who inspired this issue on Weverse DMs) became a fan and told me that I need to write about it. We’ve been discussing among ourselves the intricate fanquanisation of F1, long before a Teen Vogue piece noticed the phenomenon and talked about the “K-popification” of it. Published two months ago to Twitter’s mixed reviews, the feature reads to me unsurprisingly cosmetic, like froth on a cappuccino, failing to scratch the real itch. It is as if “K-Pop” is being used more as an engagement farming buzzword and less as a serious reference framework in research. Many, many parallels to the South Korean entertainment industry are drawn and yes, we get it, some dots are being connected.

But there’s so much more to it, and the Atlassian Williams fan zone is proof enough. It’s a special pop-up event hosted by the racing team at the heart of the city, an opening act in the lead-up to the British Grand Prix at Silverstone the following weekend. My friend wanted to go and told me to tag along for research purposes, and as soon as she saw that I wore a blue shirt, she went: you look more like a fan than I do. Behind us, in the winding queue to enter this event, were fans of various ages and ethnic groups, wearing different shades of blue to show allegiance to their team.

Inside, we found essentially a three-storeyed tong-lou with shelves and shelves of merch. Jerseys with minuscule tweaks in design and graphics, all sold separately in the £40-£85 price range. There’s the classic “地区限定”, “city-specific limited editions”, where a tiny Union Jack is sewn onto one of their regular shirts, most certainly targeting those who have travelled extensively for the game to commemorate their pilgrimage. There were also branded athleisure waterproofs, quick-dry inner layers, and windbreakers. Bucket hats, baseball caps, keyrings, magnets, the whole deal. These take up more than half of the event space, eating into the strip of ground on which (replicas of) the racing cars are parked. When people wanted to pose for a photo with the cars, they had to fight for footing with the shoppers who were waiting to pay at the till. I was laughing at how, yet again, the “main event” is never the main event in a tong-lou, and merch always reigns.

My friend pointed to what seemed like a closed-off VIP area upstairs and told me that two team members made an appearance here just yesterday. Donning the merch they were selling downstairs like idols at their concerts, both put on charming smiles, greeted the lucky fans, and even led an intimate Q&A. TikTok after TikTok were made about this moment. The fanned objects appearing in fan situations—the spatialised meaning-making I talked about before.

Downstairs in the basement, a row of racing simulators was not frequented by adult fans and only haphazardly occupied by overenthusiastic children. Games that test your reaction speed were a bit more popular, although I saw multiple grown men flushing from their foreheads to their toes out of embarrassment at how poorly they performed. My friend and I chuckled. She told me that these are real games the racers train with, either standing in a ring and catching sticks that fall at irregular intervals, or in front of an LED panel, slapping whatever button that lights up next. The whole thing felt like an arcade for the racer-wannabes, built to shove truckloads of merch into their arms to replace what’s left of their dreams.

I haven’t even gotten onto the real shocker yet. On our way out, my friend spotted someone holding some kind of flyer with her favourite racer’s face on it. According to the cashier, it is an exclusive freebie to be collected at the back of the room, provided that you register an account with Williams’ primary sponsor, Kraken. It is a cryptocurrency exchange founded in 2011 that allows you to trade 350+ currencies, including Bitcoin. A sea of people was congregating around a Kraken stand in this fanzone, fiddling on their phones to download the mobile application and become a crypto bro on the spot. A staff member will check your phone screen before handing out, essentially, an F1 photocard. My friend got to the Risk Profile Questionnaire before she decided to back out. It’s asking me to take a photo of my ID and agree to too much, she said, I feel like I’m signing my savings away. I scanned around the room, and the fans around us looked just about freshly legal. It was an insane sight to behold.

This is why the F1 fandom is not simply “K-Popified”. You are not coaxed into crypto to enjoy K-Pop. Yes, there are team colours like fandom colours, urban spectacle constructions like tong-lou, endless merchification and endless perpetuation of parasociality like in fanquan. But Formula 1 is, first and foremost, a sport historically associated with high-end motors, hence a certain class image, social status and specific lines of profession. It is now synonymous with extravagance, technological innovation, ambition and strategisation, everything our “white-supremacist capitalistic patriarchal technocratic society” champions.1 When Formula 1 gets a fan base, a certain value system gets a fan base, one which upholds the status quo of inequality. This is where the real danger lies, and a term like “K-Popification” is a straitjacket.

Obviously I’m not accusing all F1 fans of feeding a paradigm that’s draining our planet as well as our humanity. I’m only pointing out that sponsors of racing teams are more often than not asset management companies, commercial banks, computing platforms—always some kind of financial or tech entity. I’m pointing out that these entities adorn the racers’ shirts like banners in a war, that every team implicitly or explicitly invokes gratitude and awe within their fandom for this private sector support they receive. They have a much more prominent presence than, say, makeup brands that the idols are contractually bound to promote.

I’m pointing out that 6 out of 10 guys you see on Hinge would claim their ideal Sundays consist of “F1 and a Negroni”, because they want to belong to a certain tax bracket, a certain hotshot mould. Here’s what I find fascinating about F1: it unites men on every inch of the spectrum, from incels all the way to self-proclaimed “unicorns” like Dimitri the Lover. There’s something for everyone. It gives the nerds a favourite sport and long-sought manhood. It gives the jocks an air of intelligence and long-sought sophistication. It gives all of them the appearance of financial stability, technological literacy, career longevity and hence a delusion of success. The culture is the costume. The more it is worn, the more legitimacy the value system gains until we accept it as a given and nothing else will seem right.

Ironically, these “F1 and Negroni” guys will turn around and call female watchers bandwagoners. “Bimbos”, “amateurs”, fake-horny-hysterical fans who only got into the sport for the attractive racers. Charles Leclerc makes them green with envy. Women are constantly bullied into quizzes to “prove” their fan credentials, even and especially on dating apps.2 You’d find the same misogyny in every other sports fandom, except F1 has it far worse because of what I warned just now: the consolidation of F1 as a rich tech bro’s game. An article that flippantly traces the lineage of all female F1 fans to (K) pop culture will only exacerbate the antagonisation within the community. And this is exactly what they want.

The Formula 1 industry actively perpetuates the gender polarisation of its fan base, because this brings in maximum profit. On the one hand, the men will want to be decked out in a culture that screams disposable income. They will want to dabble in high-risk investment options even if they are underaged or underinformed. They will buy the branded merch to look like they also own Richard Mille watches, glossy yachts, haute couture fits or model girlfriends.3 On the other hand, the women will be cornered into demonstrating their devotion through more and more explicit and “irrational” fanning. They will buy the branded merch just to be a part of it all, and lash out on inflated Grandstand tickets where the racers can see their handmade signs of support. They will fly out to multiple Grand Prix a year, support the para-media around the sport like the F1 film and the Netflix documentaries, even if they still persistently omit or misrepresent the contributions women made to the industry. The more competition brews, the more the sponsors-racers complex earn.

Nowhere else is this more discernible than in Shanghai, where a Grand Prix took place this past March. It marked the glorious return of the event to the world’s second-most costly circuit after a COVID hiatus. The local authorities made it into a weeks-long affair, with numerous pop-up installations in the city attracting merch-buyers. They let the Shanghai Car Culture Festival fall “coincidentally” on the GP dates, so the town was already swarmed by thousands of motor enthusiasts who were willing to partake. There was a stall at a mall that had Schumacher’s helmet on display, dating back to when he won the first Shanghai GP in 2004. Nearly every Shanghai guy I know was posting some kind of awkward selfie with such archival items on WeChat. Places also sold plushies, fluffy car accessories, and everything in between, all cutesy-fied for a younger female market. One of the organisers cited a statistic that female F1 fans in China had a 35% increase this year, so they’ve “custom-designed commodities” in anticipation. The legendary Metro City Ball, a spherical billboard consisting of 3888 LED screens, was playing F1 commercials around the clock. There was an F1 Fan Festival at the north Bund, a 600 metre long racing-themed “corridor” full of rare and discontinued luxury cars to admire, standees for everyone’s “打卡” photos, merch and more merch. Female and male F1 watchers, both catered to and serviced, but also implicitly split into separate camps and endlessly tempted to spend.

According to a news article on the Shanghai Government’s website, this fan festival was directly commissioned by them as an example of “intersectional” leisure, merging “文旅商体展”, “culture-tourism-business-sports-exhibition” into one mega-occasion of public consumption. It was an opportunity to “channel F1 from the professional realm into urban life”. There were outdoor stages for live bands, EDM DJ performances, street food vendors, and a whole side project with Asia Pet Exhibition that somehow brings puppies into the picture, just to throw it in the mix and get more visitors.

To ensure the smooth running of the festival, the Hongkou district had set up a task force that liaises with the district-level Business Bureau, Sports Bureau, Publicity Department, Social Worker Department, Department of Green Spaces and City Appearances…and the list goes on. They wanted to turn the F1 “traffic”, 流量, into city-wide “stay-ffic”, 留量, meaning tangible gains for Shanghai (the word-play works better in Chinese, sorry). The final result is a 30% growth in total GP box office compared to the year before, and a 111% growth in web searches for the keywords “Shanghai F1” throughout that month. Searches for hotels near the circuit increased by 105%. Cheaper deals that package a Single Day Entry to Shanghai Disneyland with F1 tickets managed to bring in 70% of overall watchers from out-of-town, and 15% of overall watchers from abroad. In 2024, the GP boosted the economy by 1.4 billion yuan, and 2025’s figure will only be higher. Fan-targeting urban spectacles sell, big time.

Another Xinhua News article boasts of the new technology being implemented at these fan events. Drones were used for aerial crowd patrols. Humanoids and robot dogs were operating on the ground and helping police forces with “multi-view image transmission and information study”, whatever the heck that means. Autopiloting minivans were chauffeuring the audience to and fro various places of interest on the GP premises. F1 fans from all over the world were described to have been in awe of these innovations and thrilled to experience “中国智造”, “Made Smartly in China”. Do you see what’s happening here?

The Grand Prix in Shanghai is clearly a question of national pride. An opportunity to demonstrate soft power, to recoup the loss of global prestige in the pandemic years, to beckon trading partners and to rouse domestic morale. The seemingly benign spectacles are but the frontispiece, the icy surface of a lake that goes down for miles. Underneath it is a story of co-opting fanquan for a larger purpose, for “stay-ffic”. A race car with a relentless engine is herding fans to the bottom of the spiral.

It is within this context that the “K-Popification” of Formula 1 should be considered. Figures like Zhou Guanyu, the first and only Chinese driver who made it into Formula 1, are infinitely more multi-faceted in this light. He’s generally well-received by the public, even though he is currently the reserve driver for Lewis Hamilton and Charles Leclerc at Ferrari, lacking the dominance other Chinese Olympians possess in international competitions. Finishing at No.14 in the Shanghai GP, he was there mainly for…publicity purposes. He appeared in photoshoots, interacted with his fans, spoke positively in interviews about the emergent F1 market that is China, with its 200 million audience community that will only grow. Of course, he had a merch line dedicated to him, named Little Zhou’s Cute Daily Life (小周的可爱日常). He has a relatively humble social media presence (2.7 million on Weibo compared to Verstappen’s 4 million on Twitter), average build, standard upbringing and an ordinary face that the internet hasn’t obviously thirsted over. So what does that make him?

He’s a subpar contestant for the motor sport fans, but he still needs to be supported for his symbolic value as the face of the nation. He’s part of an entitled class that the average netizen now loathes, but he’s not famous enough or flashy enough to incite any real controversy. He has no academic achievements or a magnetic personality that enhances his aura, but he still hangs out with Jay Chou and sits in Ferraris. He has been pan-celebrified, but he’s not attractive or undeserving enough like Ding Zhen to turn the internet against him. He sits a bit uncomfortably for everyone.

Other “A-lister” racers are even more awkwardly balanced in the Chinese fan space. Yes, Max Verstappen is widely loved, but he’s still a Westerner leading the charts of a Western sport. The race is still a problem of race. Female fans of foreign contestants are frequently accused of “betrayal” and worse, slut-shamed for their “sucking up to rich and white people”.

The future I’m envisioning for Formula 1 in China is filled with disarray. As Shanghai renews the Grand Prix contract for another five years until 2030, I can only imagine more hype and fanquanisation for the motor sport on the Chinese internet. I wouldn’t be surprised if the A-listers open official social media accounts on Weibo or Xiaohongshu, and do large-scale fan signs and fan meetings. I would bet good money on Zhou Guanyu signing with an entertainment company and going down the idol route: magazine shoots, ad cameos, even concerts. He needs to lean into a persona that’s more clearly defined and therefore more lucrative. Meanwhile, traditional celebrities will piggyback off of the F1 traffic and start to appear at races, causing their fans to do the same. This is already occurring with Blackpink’s LISA being the first person to wave the chequered flag at a GP outside of South Korea. Even more influencers will be invited to a genuine fan’s dismay. GP prices will soar and scalpers will become employed. With the success of the F1 movie in domestic markets, it is guaranteed that more will be made. A motor-sport themed romantic drama is most probably in the pipeline. Merch are already bulking up in the factories. Hell, I saw a parody account on Twitter today fibbing that Lewis Hamilton is releasing his own Labubus next week. Who knows: maybe he would take that on board.

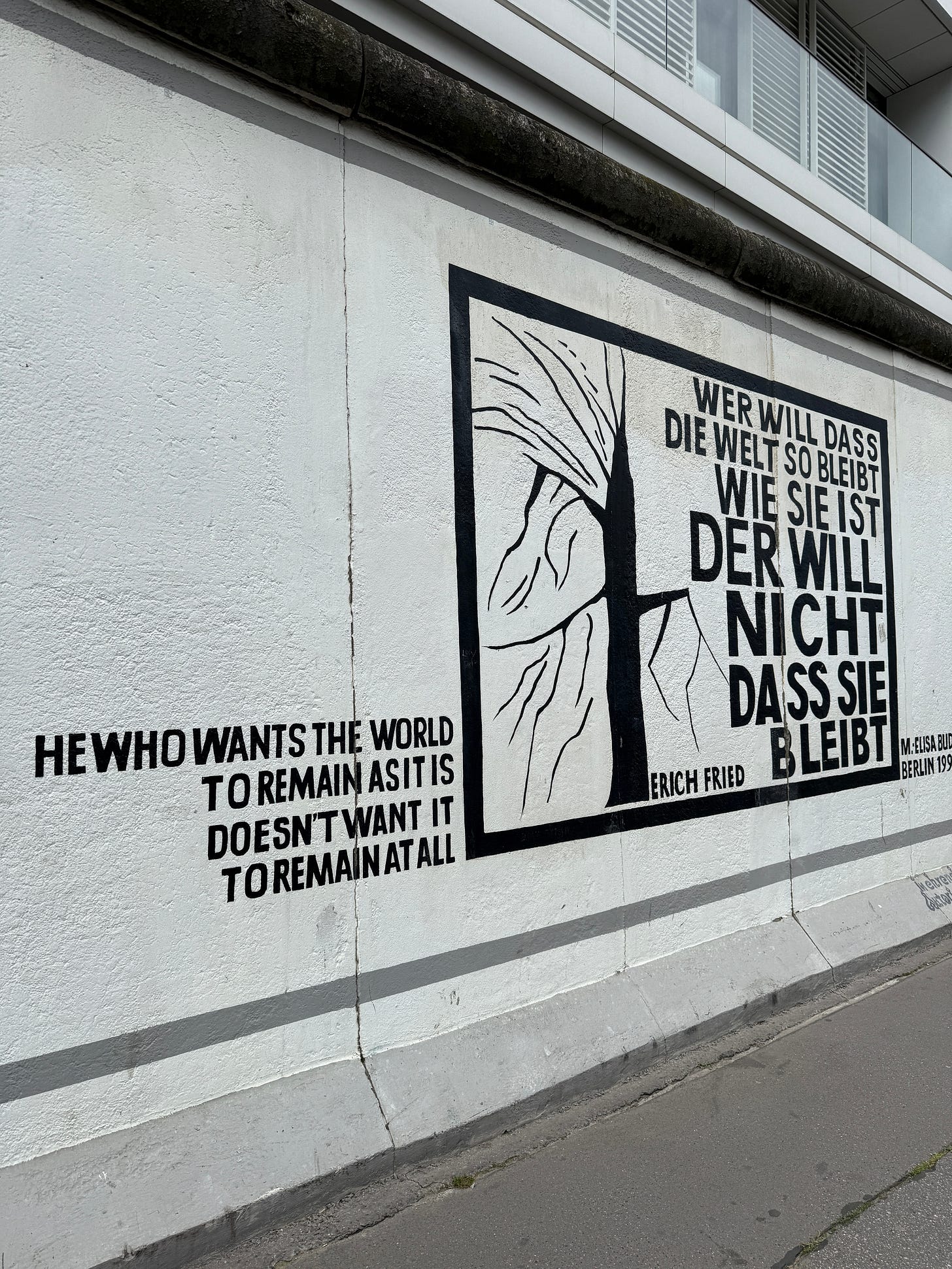

All of these projections amount to one daunting reality, that fans will be sold a value system that keeps the current society intact. I’ve written before that fanning is a political act because it is always about taking a stance and forming an opinion. Here, the stance that we’re shoved into is one of inaction and complacency. Of believing what we’re told and celebrating what’s already been celebrated. To quote a mural on the Berlin Wall that I visited this week: He who wants the world to remain as it is doesn't want it to remain at all.

Original quote from bell hooks and the italicised are my own addition.

The original tweet has been deleted, but it was a screenshot of a conversation between a girl and a guy about F1, where the guy asked a bunch of questions to grill the girl.

Irrelevant to the issue, but I just think it’s fascinating how the F1 fan stalkers bust out a yacht tracker.