05. There Are No Stories Left

ita bags, pain culture, urban landscapes takeovers, merch-ification, the pink fox and modern storylessness

1Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Much to my shock, Mary Oliver now sells merch. You would think a Pulitzer-winning gem of a poetess who writes about “earth-talk” and wild geese would be against the commercialisation of it. She probably still is. The Mary Oliver Store is allegedly launched by her descendants in the wake of her renewed popularity among Gen Z granola girlies. And I find, in horror, how this mass merch-ification of cultural themes and materials is a full-on epidemic.

Today, let’s talk Pain Culture.

SEVENTEEN is celebrating their tenth year in the industry, which I already wrote about.

The K-pop group’s official Bilibili account also posted the following notice today:

“SEVENTEEN’s fifth album ‘HAPPY BURSTDAY’ themed tong-lou opens today for a limited run. CARATS, please give it lots of love!”

Underneath this caption, you’ll find pictures of an entire shopping mall’s interior being plastered by the group’s colours, logos, album concept motifs, flashy decorations, life-size standees, makeshift stages for fans to dance on, stalls, a projector screen that blasts their music videos and more. Floor-to-ceiling posters hang in the courtyard like murals in a chapel. The members’ headshots for this comeback beam at every shopper in every direction, like stained glass windows depicting stories of suffering and redemption. Behold, my readers, the latest monstrosity we now face in the showbiz: entire building takeovers, or tong-lou (痛楼).

Let me explain the origin of the term. It came from 痛包 or “Ita Bags” in Japanese, a kind of transparent carrier designed to showcase someone’s collection of anime merch on the go. The fan would place inside it a heaping amount of items, including but not limited to badges, figurines and the original mangas. Of course, a competition of the most elaborate design, the most satisfying arrangements and the rarest, priciest merch ensues. It’s a mobile museum of devotion.

Much of that devotion is demonstrated by repetition, which is still widely regarded as the essence of an orthodox Ita Bag. People like to line the bag with an obscene amount of the same thing, bought in bulk or repeatedly, as they become fixated and hooked and all of that admiration boils over and threatens to spill. It’s why the verb for making an Ita Bag in Chinese is “扎”, probably referring to tying up the loose ends. I suspect that this is exactly why Ita Bags were invented: there has to be a vessel for obsessions and overconsumption. It’s born out of the necessity that “all of this has to go somewhere”.

痛 or Ita means, literally, pain. Japanese call these pain-bags because of the sheer amount of pain-slash-secondhand-embarassment it causes for the spectator to see just how much these roaming “otakus” can lash out. It’s too outlandish. It’s too loud a proclamation. Protruding egos grate on the average bystander’s consciousness.

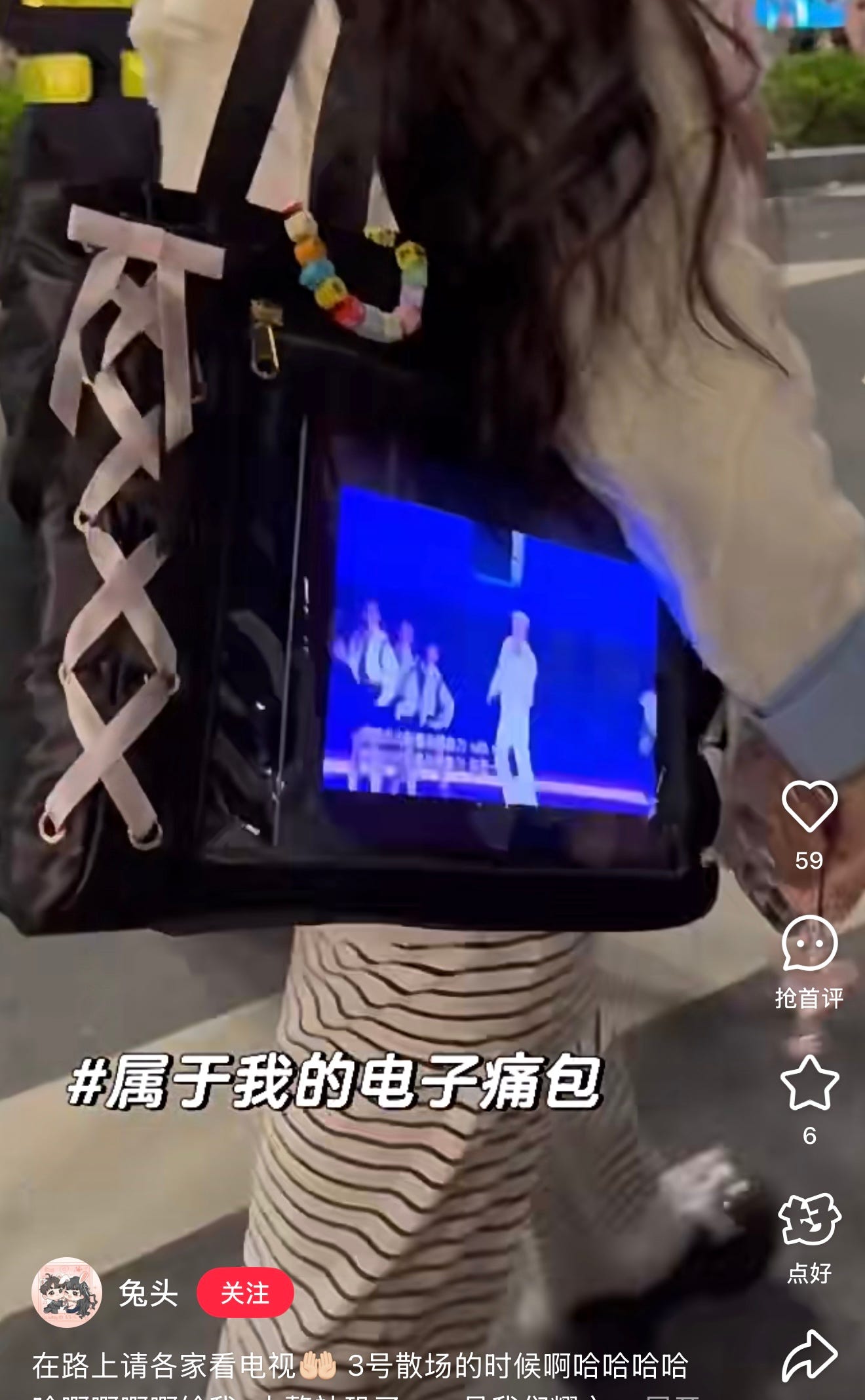

In recent years, pain-bags spread to the K-pop community for reasons unknown. If I have to hazard a guess, it might be related to how concert venues often only permit transparent carriers for safety purposes. That’s where I first noticed them anyway. You’ll find multiple vendors selling them on the street outside of major shows, but most people would be prepared enough to lug their own over. Trust fanquan to then turn a begrudging obedience of rules into the pageantry of displaying their prized possessions. In the K-pop circles, these are photocards, image pickets, slogans and stuffed dolls. If you are nifty enough, you can even sneak in a camera or other prohibited items. It will be safely shielded by the mesmerising amassment of thinginess. I’ve also seen a genius fan who cued on her iPad an iconic fan cam, set it to loop, and stuck the screen right up against the side of her bag to turn herself into a walking LED advert of the idol. An exhibition in motion.

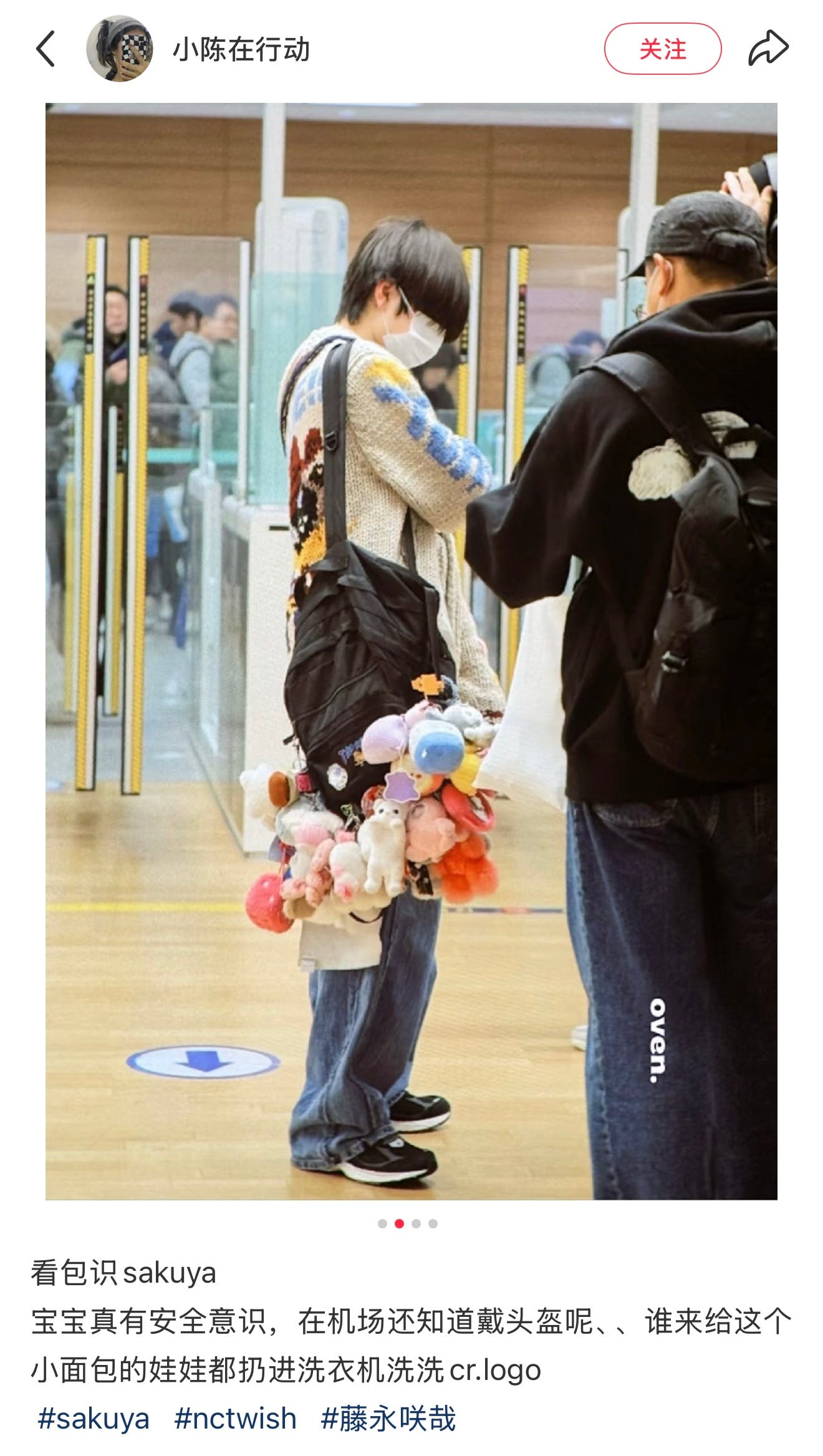

I’ve talked about wearing merch in public to make oneself identifiable to a fellow fan as a silent ritual of solidarity. But pain-bags are a step beyond your usual tour dates hoodies. The name is literal. It’s a painstaking feat to stack, compile, overfill and wedge every little artefact you own into a single showing cabinet. Every inch means every bit of love you hold and every bit of pain it brings you, and it must be in excess to prove a point and attest to its worth. In doing so, a ridiculed practice is gradually reclaimed—and reconstructed—in pride. Its global popularity is a testament to this shift in connotation, and it gets pretty funny when idols themselves start to carry similar bags too.

Here comes the twist though. It would mean something else entirely if pain-bags start to become pain-cars, pain-planes, and pain-buildings, assembled by someone other than the fan. That element of excess and extravagance is currently being administered and encouraged by the industry itself. The “HAPPY BURSTDAY” campaign is a direct collaboration between SEVENTEEN and Bilibili. Likewise, another recent tong-lou of NCT member Mark Lee’s album was set up under company instructions, and Mark himself made a surprise visit to endorse and appease. Looking at the way social media doted upon him speaking Chinese throughout the event as “top-notch fan service”, I’d say it was quite the success. But it is certain that Pain Culture, originally organic and fan-led, is being hijacked and co-opted yet again into a revenue stream. One more untapped reservoir of corporate profit to drain dry.

Entertainment companies are manufacturing celebrity spectacles in urban landscapes when the latter are not the correct vessel for it, and they shouldn’t be the ones who attempt it. When this happens, the focus is less on the performance, the performer, the spirit, the art, the enjoyment and the emotional connections. It’s about scale, surplus, visuality, aesthetics, statistics, commodities and sale.

Don’t get me wrong. From a fan’s point of view, I think tong-lou could be quite fun in theory. It’s something all of us have imagined before, a designated safe space where everyone’s an ally and you stand tall together in your faith to have some fun. But that’s what concerts are for, and a shopping mall shouldn’t take on the role of the stadium. It is no wonder that tong-lou picked up momentum in mainland China under the ongoing Korea Ban (although I doubt for long since HYBE set up its subsidiary in China this week). It has stepped in to replace the live music experiences fans are deprived of. What is also achieved is the association of fanning with merch-buying.

Your average tong-lou would consist of so many shelves of “goods” or “谷子”, a term for content-related commodity that came from the anime fandom. A stimulus for purchase at every corner. And once they are done browsing the “tong” sections, fans would probably spend some more money elsewhere in the mall. That’s why I put a dash between “tong-lou”. They are separate entities, spatially and notionally, but mutually reinforcing nonetheless. It doesn’t help when numerous shopping complexes in China are already arming themselves with these miscellaneous-cutesy-items-stores in their basements to attract young spenders. In these spaces, the Cultural Content is completely crowded out and obliterated. In its ruins stand an acrylic keychain reenactment of it, and popsockets, phone cases, pens, pencil cases, portable chargers, price tags. It is oppressive. It was what Seoul felt like as a city, which I wrote about in this special dispatch.

I went down a research vortex about the malls that are contracted to become tong-lou. My aca-fan instincts tingled and told me there’s something bigger at play here, a nastier game with higher stakes and astronomical yield. I was right. Mark Lee’s tong-lou was hosted by the JD Mall in Guangzhou, its mother company being the rapist Liu Qiangdong’s e-commerce platform JD.com Inc. The official tagline of the mall is “潮购科技”, where “trends” and “tech” are highlighted. The company’s first real estate venture in a top-tier city, JD Mall boasts 30,000 square metres of “hybrid retail”, where webstore-only brands like Redmagic and Narwal can display their products in a physical store for the first time. Consumers can walk around the place scanning “electronic price tags” in the JD app and place an order on their devices. It is embedding popular commodities in the virtual realm into a tangible reality. Sounds familiar? Mark Lee is but among the cleaning robots and the smart speakers, one of many pixels on a digital shopfront, temporarily stepping out of our imaginations to be felt.

As for the BURSTDAY tong-lou, it was housed in Shanghai’s Times Square, one of the oldest shopping structures of China, developed by the state-backed real estate giant CRC (华润). First founded in 1997, Times Square was a forerunner in the department store craze at the peak of the millennial euphoria. It got a new face in 2019, setting its target demographic as “高知高智女性客群”, “highly-educated women with high IQs”, and its commercial positioning as a “Beauty Theatre”. This is a paragraph from the Elle Magazine commentary of the place:

利用现有的空间特征,设计师将剧院的元素贯穿到建筑的每景每处,项目内部大玻璃穹顶的设计、幕帘装饰、弧形拱门、错落露台等,一切都按照经典剧院的元素进行设计。“剧院式”的行走动线形成整个商业空间的特色,消费者在随意走动于各个功能区时,无论视线停留在何处都具有可看性,给予消费者自在、舒适的重参与感的消费场景。

为购物场景赋予更加丰富的内核,满足消费者在购物之外的情感和社交诉求,华润置地打造出的是一个融入生活美学的无边界社交购物体验空间,一个具有温度且富有社交感的精致商业,一个不断激活消费者探索欲望的创新消费场景。

Using the existing spatial characteristics, the designer instils elements of the theatre throughout the building everywhere, down to the large glass dome, curtain decorations, curved arches, and staggered balconies. The “theatre-style” creates a unique movement pattern that is the place’s signature attribute, where consumers can admire and appreciate each functional area during their amble, giving them a relaxed, comfortable and participatory consumption scenario.

By introducing a richer core to the shopping scenario and satisfying the emotional and social demands of consumers outside of consumption, CRC Land creates a borderless social shopping experience space that incorporates aesthetics of life, an exquisite business with a sense of warmth and socialization, and an innovative consumption scene that constantly activates consumers' desire for exploration.

Need I say more as to why they agreed to be a tong-lou?

In all seriousness, I think it’s concerning that shopping malls need the extension pack of fans to boost their footfall. The emergence of tong-lou is a recession indicator, despite the deceiving facade of fanfare (pun intended) and prosperity. We’re fast approaching an inflection point and we’re about to have the longest way to fall, because merch-ification and spectacles mean there aren’t any stories left.

You would know about LinaBell (玲娜贝儿) if you’re remotely active on Chinese social media. This is a character and a toy line created by Shanghai Disneyland in 2021. She’s a fluffy pink fox with Barbie eyelashes and no narrative background. Unlike other characters in the theme park, LinaBell is not adapted from any source materials produced by the animation studio. She does not exist in any art form. She came out of thin air and into instant internet virality with her flirtatious “personality”, perfect looks and adorable gestures. She exists because merch has to be sold and Douyin clips have to be filmed. That’s all there is.

Because no content serves as “canon” to what LinaBell is as a sentient being, people form instead entire fandoms for the various “内胆”, “inserts”, who are the actors and actresses inside the costume. The most famous of them are nicknamed “堆堆”, “小七” and “小九”, “foldover”, “calf-length” and “ankle length”. This is based on their height which affects how the fabrics look on their legs: creasing and folding over at the bottom, cutting off at their calves or at their ankles. But hardcore LinaBell fans would be able to identify the “insert” on duty that day by their demeanours. Each of those staff members, apparently, interprets LinaBell differently (foldover is the most popular), and the subtle differences are picked up and analysed and fanned. Sometimes people would wait for hours or stake out at the park for days to meet the LinaBell played by their favourite “insert”. In fact, I hated this immeasurably dehumanising term so much in 2021 that I almost wrote my dissertation on LinaBell instead of Produce Camp. If that had happened, Active Faults would not exist at all. But here we are today.

Back then, I knew the LinaBell model would get replicated again and again, because I had gone to Disneyland and seen the hype for myself. The store was teeming with pastel pink fluff and every garment imaginable was made foxy, from backpacks to t-shirts to scarves and hats and gloves. Four years on, Shanghai Disneyland has also introduced New Year’s blind bags of character merch, including ones of LinaBells, to be purchased like lottery tickets. She has dethroned the previous “Queen” of the park, StellaLou, who is a likewise storyless rabbit and a consumer favourite. According to statistics, if you stack up all the StellaLou merch ever sold by Shanghai Disneyland, it would be the equivalent of 119 Mount Everests.

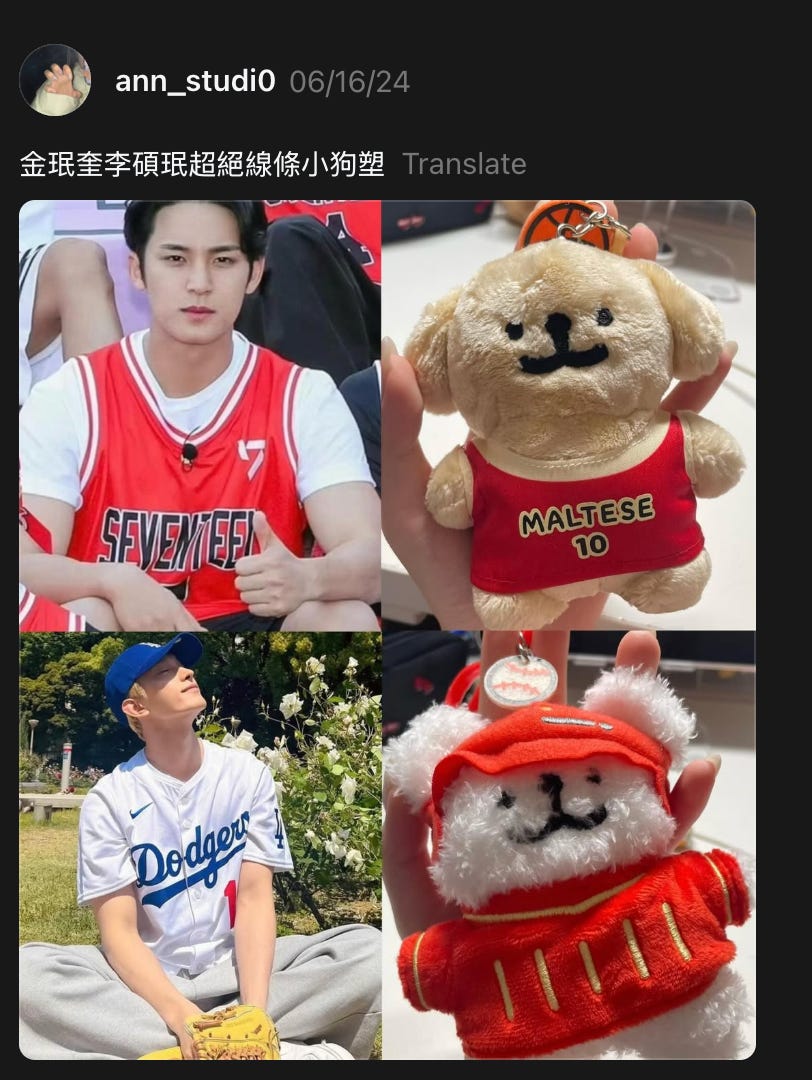

A friend who works for Disney Studios told me that no one at the Los Angeles headquarters knew who the fox is or what the fox says (sorry). Shanghai Disneyland has created a symbol so siloed that the staff is unaware of it. Look beyond LinaBell and you’ll find Butter Bear in Thailand, The MoonLab Maltese in South Korea, and, most recently, Labubus from PopMart that got grown men into a fist-fight at Westfield Stratford. Merch-ified viral social media phenomenon, zero context or storyline. Then there are others with a little bit of plot to go off on, but the merch-ification is blown way out of proportion to its source materials. In this camp, I want to nominate Chiikawa, Zanmang Loopy, and Kirby, as well as all of Sanrio. Nowadays, idols would be likened to these characters by their fans, not to provide the characters with a backstory but to appropriate their characterisations for their celebrity persona. Two hollowed-out symbols to drive up consumer demand.

You might correctly argue that this creation of characters purely for the sake of merchandise has been around for ages. Just walk into a MINISO and try to name anything’s hometown. You wouldn’t be able to. The success story of PopMart is founded on this model. And yes, there’s nothing wrong with not caring about the back story and simply finding something cute and purchaseable. But that’s not my point here. The point is that we are losing interest in story-telling.

Placing merch over content signifies a change in the way we fan. From empathising with another being to admiring its appearance. From enjoying artistic expressions to owning commodities that represent them. From understanding a narrative to displaying an association with it. Behind it is a change in the way we prefer to receive and process information: from words to pictures.

I was listening to a podcast episode where “站姐”, fan photographers, discuss the latest preferences in celebrity photos. No more airport fit check photos, professionally lit and staged, or pre-award show getting-ready photos in flawless makeup (出发图). No more photos flaunting brand deals, all decked out in luxury accessories, most certainly fearing backlash like the actress Huang Yangtiantian.

Instead, fanquan craves blurry, unedited, authentic, accidental moments of beauty that can only be caught by chance.

The latest neiyu trend is “撕拉片”, peel-apart film or pack film photos, which are essentially Polaroids but with the added step of the user peeling away the developed image to show the final product. Dating back to the 1900s, the technology behind pack film has long been replaced by its much more advanced descendants. But neiyu hasn’t had a viral talking point in a while, and back it came. The delicate imaging process is archaic, hence mysterious and thrilling. It requires expert knowledge, already discontinued film rolls that are as non-renewable as fossil fuel (now priced over 3000 RMB on the secondhand market), and a myriad of success factors. It has an entry threshold and a huge room for error. It became a litmus test for neiyu faces and whether or not they can withstand the trial.

Fanquan enjoys this trend because of that urge to debunk, debase and deconstruct. You can’t photoshop your features on film without it being extremely conspicuous and embarrassing. Equally, you can’t recreate the colouration and texture of film using digital means. It captures a moment of something close to the truth. If we are not given a story that offers slivers of truth, we seek glimpses of it in an image.

No matter how much makeup you wear to aim for a killer photo, the flash and high exposure will eat away all the window dressing. The most widely applauded peel-apart films were of actor Zhang Linghe and actress Ju Jingyi, because they’re both known to have perfect “骨相”, i.e. bone structures.

You need to be chiselled correctly to emerge from the peel-apart war victorious and proud. You need to sit perfectly still in a blinding light and let your bones be all that remains. You need to give away the truth without saying it out loud. Then another trend will sweep. You and every single word about you will be gone with the wind.

Hugely indebted to this article: https://www.cbndata.com/information/293474

This is such an interesting combination of topics. (Extremely minor side note: "ita-sha" cars, including the fan variety and not just the original meaning, predate ita-bags--in fact I remember when ita-bags were still a new thing.)

It seems like tou-lou “building takeovers” and Ita-bags are the actual metaverse. Not digital worlds taking up properties of the physical, but the physical world being taken over by digital products and fandoms.