06. Who's Driving the Bus?

weddings, Supreme hoodies, defective menstrual pads: wealth and anti-wealth in Chinese entertainment

Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

On a particularly muggy Thursday afternoon, I walked into a corner shop to get a cold drink while I waited for the bus. I picked out my Capri Sun from the fridge. I looked up from my phone to pay. And there it was, on the till, three rows of Labubu blind boxes, conspiratorily winking at me like it’s us against the world: bracing positions, laowai. You are not ready for us.

This was London’s N7, where the waxy exterior of this glamorous city starts to crack. Most people in this neighbourhood won’t be able to afford consistent heating in the winter, let alone a storyless figurine that could sell at an auction for 1.08 million yuan. Yet Labubu infiltrates. It winks and smiles with too many teeth. It dangles on the zip of someone’s Louis Vuitton bag and glows with a newfound arrogance that it is probably rarer and pricier than the brand itself. More sought-after, more relevant to the zeitgeist, and more godlike.

Today, let’s talk about wealth and the portrayals of wealth in Chinese entertainment.

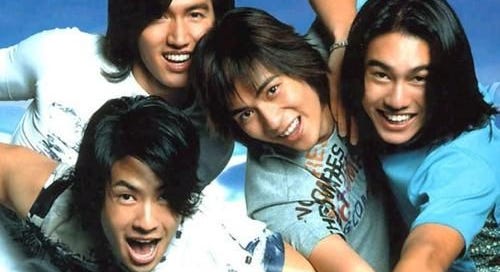

I grew up in the age of rich man drama. You would’ve heard of the era-defining Taiwanese series Meteor Garden (流星花园), where the four male leads were these suave scions with permed long hair and unimaginable wealth. There was also Romantic Princess (公主小妹), another hit series that followed the Meteor Garden paradigm almost down to the tee, with four rich men as love interests and a pretty damsel in distress. Both were adapted from Japanese manga, a source material that also influenced South Korean television at that time and gave rise to the likes of Boys over Flowers and The Descendants. Mainland made its own Meteor Garden in 2009, “Meteor Shower” (一起来看流星雨), and catapulted a generation of celebrities into fame that persists to this day. I could go on and on.

Back then, cultural content was saturated with portrayals of wealth, and people were still finding it entertaining. It can be and it must be loud, conspicuous, unmistakable. It was presented as pure flamboyance, and we were still willing to behold that flamboyance, observing its manifestations like infants gawking at shiny objects. Off-camera, celebrities themselves could be in possession of wealth and on the good side of public opinion. We watched with intrigue as they burned through their savings with increasing creativity. I remember the days when the entertainment column was brimming with news of jaw-dropping mansion purchases and lavish, high-profile weddings.

In 2011, singer Zhang Jie and TV host Xie Na’s wedding took place in Yunnan’s Shangri-La (the town, not the hotel chain), in a stunning national park. The choice of an outdoor location in a remote, off-the-grid part of China was avant-garde at that time. It was trend-setting. All over the headlines were stories of the star-studded attendee list, housed in the local Banyan Tree suites, or the elaborate backdrops using fresh flowers that took hundreds of workers over a week to hand-build. The hype was so widespread that it boosted visitor footfall in Shangri-La that year. The local government allegedly foresaw their sway on provincial tourism, and generously covered the expenses of their wedding with the fiscal budget, all 30 million of it. This is now an unimaginable administrative decision.

In 2015, actor Huang Xiaoming and model Yang Ying (also known as Angelababy) had what the media dubbed “Wedding of a Century” (世纪婚礼) in Shanghai Exhibition Centre. This was our William and Kate, or the Ambani and Merchant. The location choice alone will tell you enough about the scale of this spectacle. The whole thing cost over 200 million yuan, with over 200 tables of guests that totalled over 2000. Half of the Mandarin-speaking entertainment industry was invited. Floral arrangements were completed by an expert team in France and remain the largest ever wedding setup in the country. Ma Yun filmed a congratulatory video for the newlyweds. Yang wore a tiara on loan from the French luxury jewellery brand Chaumet’s archival museum. They divorced in 2022.

Back then, the country was getting a kick out of living vicariously through the rich and their Kardashianic ways. It is no wonder that China’s “luxury department store king”, SKP Mall, was opened around this time. Portrayals of wealth in the entertainment industry had a knock-on effect in people’s private lives, as we started to mimic the aesthetic. Awareness of luxury brands spread like a chant in a stadium. China and, dare I say, surrounding parts of Asia, were all about logo maximalism. Stacking item upon item on your body until you are a walking heap of cash. It was about wearing as much of your disposable income on you as you possibly can, all at once.

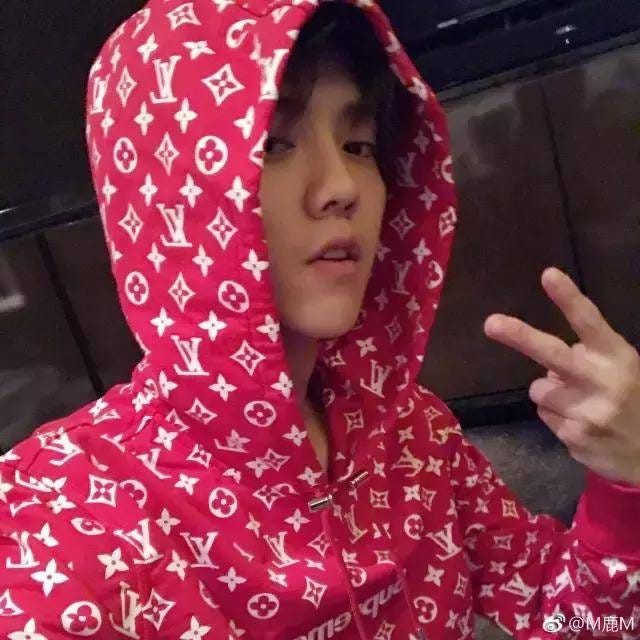

The first generation of “traffic idols” played an integral role in this. Glorified by a successful breakout in K-pop, the ex-EXO members returned to China as war heroes and we built their Arches of Triumph with likes, comments and views. They were constantly appearing in the public’s eye drowned in branded attire, the flashier the merrier, encouraging their fans to mirror their moves. The other day, I listened to a podcast episode that analyses Lu Han as neiyu’s founding father of “traffic” (流量), and it jogged an ancient memory: teenager me searching for the same Supreme t-shirt he wore in a retailer in Sanlitun. I only knew the brand because he was obsessed with it, and I was obsessed with him. I couldn’t find it, and even if I did, it would’ve had a 5-digit price tag. I didn’t know you could sell t-shirts like that.

Traditional luxury brands like Chanel started to drift to the sidelines as edgier designers invaded the market with their statement pieces, like Supreme, Balenciaga and Off-White. Their products are as expensive as they are scarce, often released in bulk and never manufactured again. This was when virtual marketplaces like “得物” were in vogue. Founded in 2015, it is essentially eBay but for collectable trainers. This was the era of “drops” and “drop alerts”, where people started to have an appetite to snatch limited editions and exclusive versions, ready to bid up prices into the six or seven digits. If Lu Han and Huang Zitao are wearing Yeezys and Supreme x Louis Vuittons, then we must wear them too. “得物” lost its hype as quickly as it gained it, as the application’s “authenticity guarantee” got repeatedly violated by the resellers. People kept complaining about purchasing dupes, and it got flushed down the drains.

By this point, wealth as seen through the entertainment industry was still pecuniary surplus, the sheer accumulation of money and display of commodities. But a subtle and irreversible change was starting to occur. Wealth was no longer just about money, but access. We were entering an era of scarcity and rarity as value, and wealth as increased means to fulfil desires. Then came Idol Producer and the era of xuanxiu.

The script was flipped after that. Entertainment and the wealth it is capable of creating were now participatory. Fan consumers were told to buy yoghurts, drone shows and billboards, so that celebrities can access the industry, benefit from the rare opportunity of an idol group contract, and meet their career goals. By doing so, fans also felt like they had gained access to those who were inaccessible, the scarcest, rarest faces that we desire. Fans owned celebrities like commodities, and the system owned both. A narrative about love and devotion is spun. We willingly pay more and more to create an illusion of demand for our beloved on the market and increase its value, only to let others reap the rewards.

The ambassador battles were reflective of this shift. This was when neiyu personnel started to compete for the most luxurious brand to endorse and boost its sales for, the most high-end retailer to become the face of. Fanquan subsequently armed itself with knowledge of the “blue blood brands” (蓝血品牌), meaning those with centuries worth of history, exquisite quality of products, staggering prices and real symbolic capital. We were schooled in differentiating the weight each contractual title holds, and they were endless. “Friends of the Brand” (品牌挚友), “Ambassadors” (品牌大使), “Brand Representative” (品牌代言人), “Product Representative” (产品代言人); Global Rep, APAC Rep, China Rep, Mainland Rep; Seasonal Rep, Year-Round Rep, Main Brand Rep, Subsidiary Brand Rep. These titles have different contract lengths and pay grades, which translate into a celebrity’s overall business value (商业价值): how much they can get their fans to spend on the brand with their face, and for how long. This places them somewhere on the pecking order of the industry, and determines their level of stardom (咖位). This positioning affects the gigs that will land in your manager’s inbox, the quality and quantity of the “resources” (资源) you get. It was so crucial that everyone had a precise positioning that new ambassadorship titles were constantly created to aid a systematic classification. It was how investors knew where to place their bets to get the highest ROI. No one outside of fanquan cares even a tiny bit.

But this is what you should care about. The wealth that celebrities aspired towards was no longer more zeroes on the pay cheque, but value maximisation of themselves as well as their fan bases. It was about crafting a persona that attracts more fan consumption and hence more capital investment. You are paid so long as you make someone else pay you. To the average fan, celebrities were no longer innocently accumulating wealth, but doing so at their expense. Wealth was no longer a game we watched from the bleachers. We got roped into it.

Soon enough, people grew exhausted of being the garlic chives. “208” was coined as a term. Wealth in entertainment got rapidly equated to privilege, disparity and cruelty. And here we are today, where an actress’s emerald earrings will ruin her and her whole family’s professional lives, because wealth instigates hostility and disgust. What a journey it’s been.

Of course, this is a phenomenon that cannot be extricated from the wider economy and consumer mood that fluctuated throughout the years. 20 years ago the prevailing sentiment was contentment. A lot of people earn enough to live a comfortable life. They were confident in their life paths, and proud to be representing a fast-growing nation on its way to surefire prosperity that will trickle down to everybody. 20 years and a pandemic later, they lost that conviction.

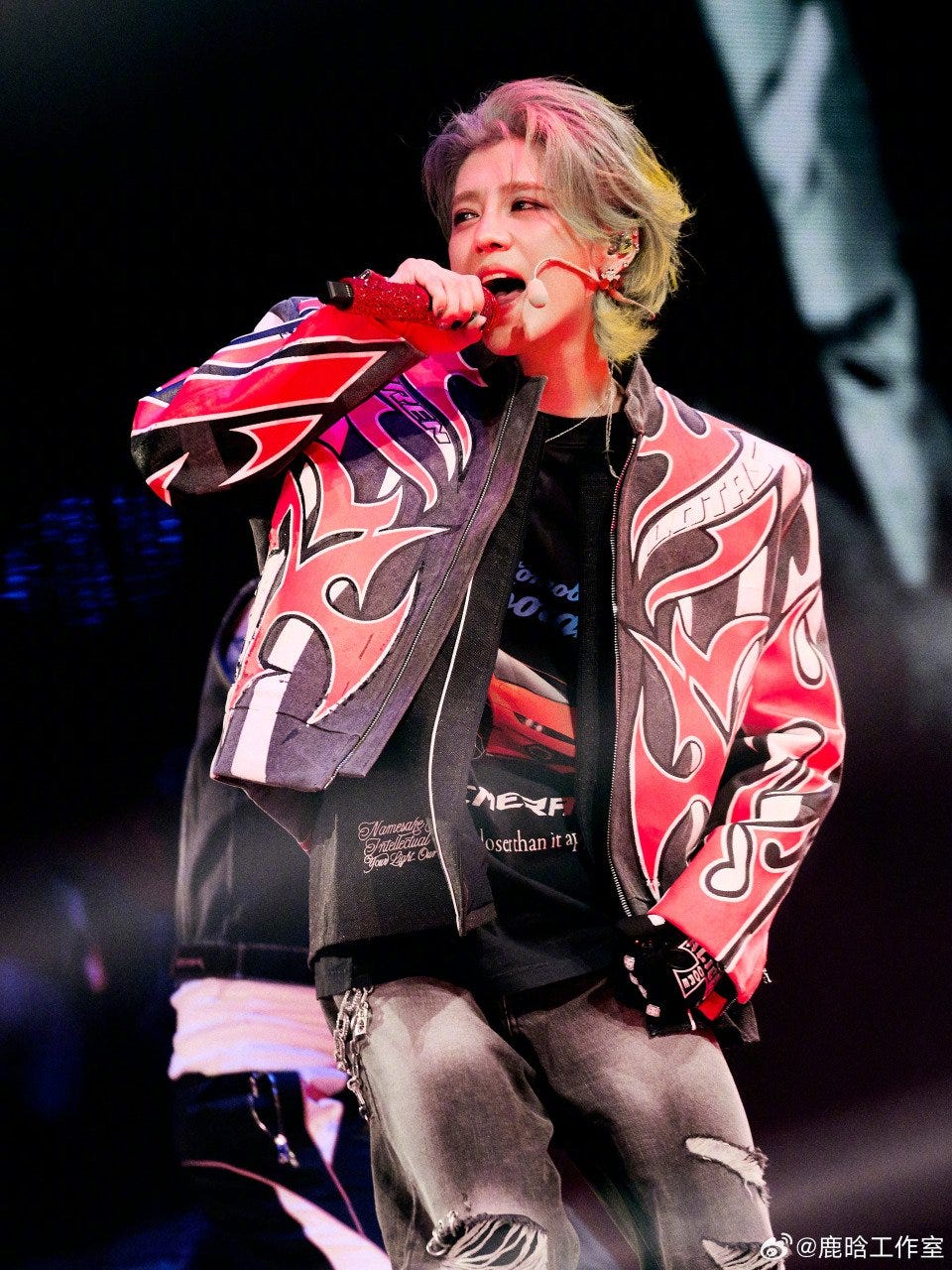

Thus, neiyu celebrities are now terrified of showing wealth. Signs are everywhere for those with the eyes to see it, from Lu Han’s concert outfits to Cai Xukun’s airport outfits.

They are increasingly brandless and logoless. One of the hotshots right now, Zhang Linghe, recently signed a deal with arguably the largest herbal tea brand in China, Wang Laoji. It is a cheap and down-to-earth favourite of the general public, like Capri Sun, something you’ll find in every petrol station and workers’ cafe. They’re starting to adopt the South Korean approach of celebrity advertising, which prioritises nation-reach (国民度) over upmarket exposure. You might have noticed how K-pop idols, especially the most successful ones, tend to move towards food and beauty brand deals as their fame racks up: Seventeen with Jongga Kimchi and Bibigo, Jang Wonyoung with Amuse and so on. They want to ground themselves in every household and within every small talk, because that’s how parasociality is reinforced and hence how the industry functions. Neiyu is forced into it for a different set of reasons, namely to avoid further scrutiny and reconnect with the wealthless common life.

One example is Huang Zitao’s latest venture in a menstrual pad brand. Targeting his female fan base since the EXO days, Huang launched Duowei (朵薇) in his live stream in May and sold over 102 million pads in the first month. He claimed his mission is to ensure that his fans feel cared for in their everyday lives, with the best sanitary products on the market. Last week, customers reported that they found suspicious “black dots” on the pad’s cotton surface. He released an apology stating that pads are industrial products and it’s “inevitable” to have defective samples. He invited CCTV journalists to do a “surprise bust” of his factory as emergency PR to show that he has nothing to hide on the production lines. One of Duowei’s business partners is Wu Yue, the head of the trade union of sanitary products in Zhejiang Province. The other partner is the MCN company Yowant, which manages almost all of the live stream sellers in China. I’ll let you add up the evidence.

My point here is that celebrities are appearing more and more in everyday settings, be it tong-lou or on your menstrual pad packaging. The days of celebrity ventures being glitzy streetwear (Chen Weiting’s CANNOTWAIT) or trainers (Bai Jingting’s GOODBAI) are still fresh in the foreground. Next thing you know, we might start to see them selling bottled water or bags of rice. It reminds me of the desperate and pathetic attempts made by politicians to seem “in touch” with the people, trodding in back alleys and through farmers’ markets, stooping down to shake some hands. You’ll see the vision too if you’ve seen videos of celebrity “floor-sweeping or “扫楼”. This is a visit to a media outlet’s headquarters to walk around the office cubicles giving out freebies, chatting to staff and smiling into phone cameras for the most “authentic”, “organic” camera interviews. The most common floor-sweep locations are Sina, Tencent and iQiyi, because of their industry-mogul statuses. Eyewitness accounts of their real-life visuals, real-life height (even then there could be something in their shoes), and their real-life scent would circulate across the net. The ones who appear the most “lifelike”, with unpretentious vibes of a “live person” (活人感), would be the most praised and fanned over.

Look towards a new reality show created by Hunan TV, Paris Partners (巴黎合伙人). The concept note reads as follows:

6 youthful Chinese business partners crash-land in the heart of global fashion, Paris, and spend 16 days building from scratch a pop-up store that showcases top-notch Chinese brands and the best of oriental beauty aesthetics. They will collectively help guo-huo (Made in China products) break into overseas markets and flaunt China’s beauty to the whole world.

The line-up includes Active Faults cameos like Li Jiaqi, a Seventeen member Wen Junhui, Idol Producer contestant Bi Wenjun, and the now-divorced Huang Xiaoming. The store opens with everyone wearing traditional Han robes and Wen Junhui performing martial arts on the streets of Paris. When they work in the store as salespeople, they’re in casual wear and pretend to be unpretentious. Fans stake out in the neighbourhood to appear in the content, buy the products, speak to the cast, and take spoiler photos for Xiaohongshu clout.

Everything about Paris Partners encapsulates the current relationship between celebrities, fans, entertainment, and wealth in entertainment. The cast wants to step down from the pedestal and appear “common” by working a regular job selling accessible makeup, especially Li Jiaqi. But they still need their fan bases as consumers who prop up the premise of their project and increase their business value. This value maximisation has to be “red-washed” into a nationalistic, soft power campaign because of the renewed hostility towards celebrity wealth and self-interest. In the end, all the content filmed will be released behind a paywall to further exploit the fans back home. As they consume the content, they will be prompted to buy more products from the brands and more traffic to increase the visibility of the show, hiking up business values all around. Full circle.

If you look beyond entertainment and fanquan, you’ll still see that wealth is a prickly thorn in everyone’s eyes and the wealthiest are being turned into the butts of jokes. Two viral reel creators on Bilibili and Douyin nowadays are @戏很多的金兑 and @小付同学Chloe, who parody Shanghai mid-upper-classers and Beijing mid-upper-classers, respectively. The former does a series of fake street interviews and acts out your standard Shanghai bunch: the “French bistro owner”, the “curator”, the “luxury buyer”, the “barista”, and the finance bro in Lujiazui. They mix in random English words as they tell you about their personal trainers, favourite French wines or lobsters. The latter does a series imitating different kinds of Beijing taxi drivers while wearing a traditional King’s robe. She nails their sweary, cocky, entitled demeanors with such accuracy that I the Beijinger can vouch for. In fact, she hit the target a bit too hard that Xiaohongshu censored all of her posts. Their collaborative video of a Shanghai Boyfriend/Beijing Girlfriend street interview got over 3.6 million views.

It feels to me that fanquan and the wider public are yanking the tablecloth down because they can’t move anything on the banquet table. We want to see the moving parts of flamboyance crumble and fall. We pull and we see the glistening silverware, the candelabras, platters after platters of delicacies, all toppling over each other at the impact and instantly losing their appeal without the pristine backdrop.

I wonder, then, if we’re approaching the end of celebrities as we know them. A fundamental constituent of fame is glam. If there are no stories left and the best bones leave but a moment of beauty behind and wealth can no longer exist to set them apart from us, how should they stand out? Why are they any different? Are we just flipping them like hourglasses as we scroll down our screen to pass our time? Are they vessels of our in-between state, the limbo space between work and meagre rest?

As stan twitter would put it, if they don’t want to be celebrities and we don’t like or want to be celebrities, then who the hell is driving the bus?

My answer: probably Labubus. The people and things that are genuine anomalies will be famous next. Wealth will be about eccentricities, novelties, the anti-wealth. It won’t exactly be about resistance to the existing structures, but it will be something cute and ungovernable, ready to smile with too many teeth.

that june 7 look is fire tho

It's telling--to me, at least--that there seems to be this broader cultural exhaustion with fame, glamor, and spectacle, both in the US and in China. And yet we still feel compelled to spend LOTS of money on public, visibly-online status games.

idk call it a recession indicator I guess?