04. More than a Fan

Internal Struggles within Fanquan

Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Previously on AF: traffic topping idol Jackson Yee’s employment scandal serves as an example of political discussion enabled by the entertainment context. His image of a morally upright celebrity worthy of appreciation is now defunct.

In this issue, I want to show you another side of the scandal which news articles will definitely not cover. Fan reactions to such controversies are overlooked at worst and included only to further the brainless fanatic narrative at best. Fanquan is misconstrued to be unified, inherently partisan and in a constant head rush of blind admiration.

I beg to differ.

Birdies

It has to be said that most “birdies”, Yee’s fan base, went on to support him as usual. Besides the routine tactics of counteracting the antis, they have adopted an astonishingly wide range of disruptive discourses to stand by his case. Some accentuate that he is a lawful citizen who deserves bianzhi and the government subsidies that comes with it as much as everyone else. Applying for bianzhi is a basic human right, one fan argues, and there shouldn’t be any obstacles if Yee abides by all the rules. What’s unfair is hindering a celebrity’s access to bianzhi because of their fame. Another post sides with Newsweek (see previous issue) and states this: “all of you scream injustice but it’s nothing more than just scapegoating others to vent about your own failures”.

By far the most intriguing argument posited by a birdie is an account of their own success at securing bianzhi. The OP writes:

Received confirmation today that I got bianzhi ranking 2nd in the test. This is the result of a process where I earned recognition only by working very hard. I know very well that I couldn’t achieve this before because I was lazy, not because Yee took my place.

They go on to further absolve Yee by reminiscing on how hard he worked at the beginning of his career (namely taking very long bus rides to art school every day, using cutting boards as writing desks for his homework, sacrificing playtime and childhood to excel at dancing). They conclude with this punchline: “there’s only one rule in this world. Resources always tilt towards those with capabilities”.

Though the authenticity of this account is questionable, note how talks of rights, capabilities and social justice emerge where you least expect them. Out of love for Yee, birdies defend him with a (misplaced?) civic consciousness. They interpret Yee’s privileges as entitlements.

The Empire

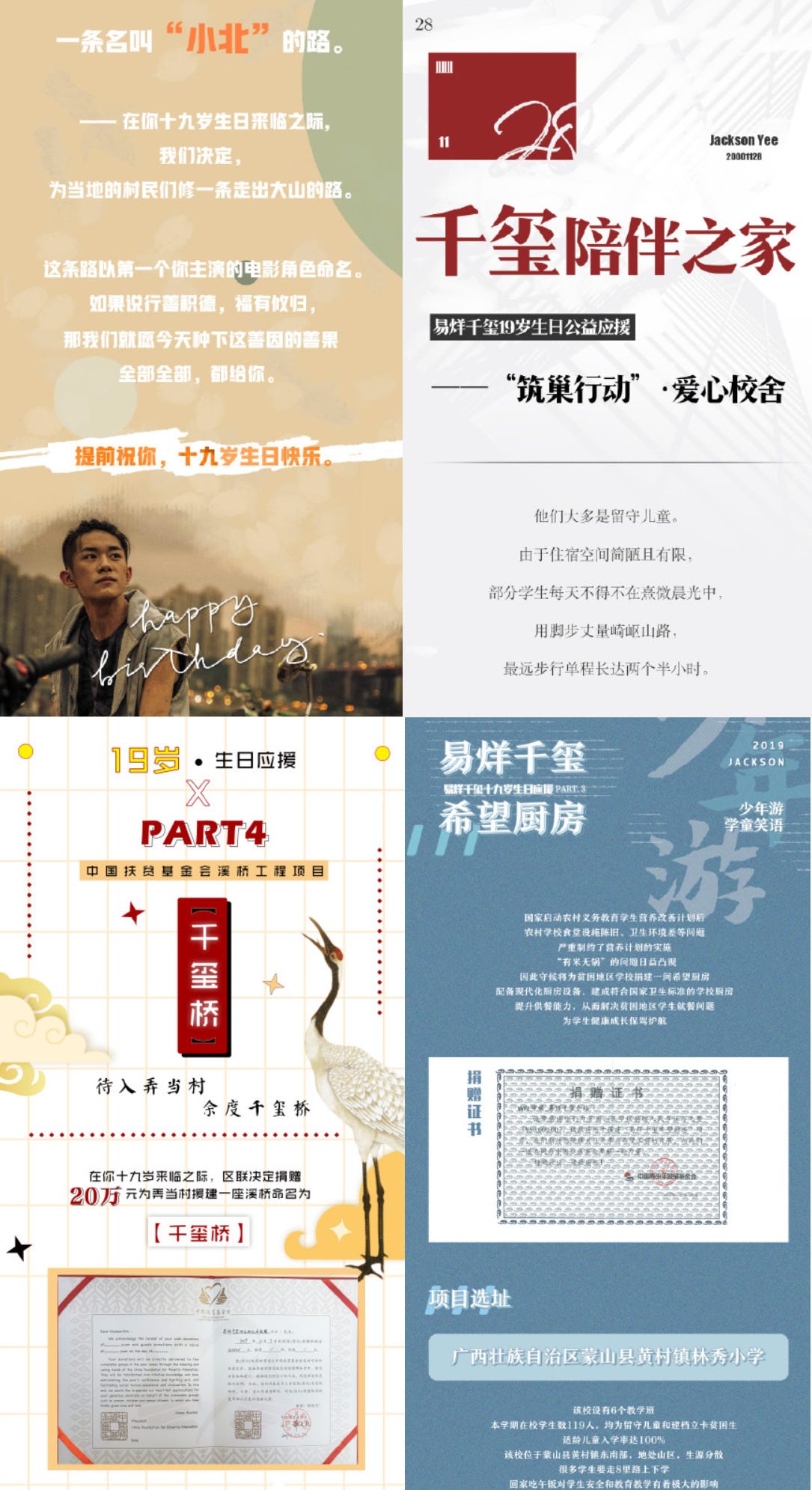

Fans of fostered idols like birdies are known to be fiercely loyal, remarkably committed and proudly combative. Because they are heavily invested in the idol both emotionally and financially, the typical mindset of fostered idol fans is like those of helicopter parents. Birdies have done everything everywhere: from buying him billboard ads and drone commercials to helping him with homework and compiling gaokao revision notes to get him into a university.

Together with fanbases of the other two members of TF Boys, they are collectively known as the Empire (帝国). TF Boys fanquan, despite being one of the most examined topics in Chinese fan studies, remains unfathomably complex. Onlookers named them “the Empire” in a derogatory tone to condemn their tyranny, but they take pride in their reign. The name is really quite apt - they are explorers, soldiers, and more importantly colonizers.

They changed Chinese fandom dynamics once and for all. The Empire pioneered numerous toxic practices in fanquan that are normalized today - chart-topping, repetitive voting, comments controlling and so on. They were first-generation data labourers, parading their machine-like ferocity as they earn a No.1 for the boys across all rankings. They are the OG of fan wars and intra-group competition, demonstrating their allegiance using colours in draconian precision.

One “imperialist” claims in a Zhihu thread that all are proud of their achievements in the past. They bit a piece of cake from the top dog at the time, K-Pop, as they chart-top TF Boys’ low-budget earworms. Coming from an imperial background is a seal of approval itself, an intimidating presence even after one has left that life behind. It’s the highlight of one’s fanquan resume.

Their pride is not unfounded. The Empire has never been monolithic as a fandom.

They are beyond fans or consumers on many occasions. They are the inventors of malleable LED signs after the parent company of TF Boys banned LED sign wars at events, like in the picture above. They allegedly hold the patent to this kind of soft, paper-thin signs that can be conveniently sneaked into the venue.

They are also the first to launch large-scale charity campaigns in the name of the celebrity to boost their reputation and do good at the same time. They’ve built schools and libraries, bought lunches for underprivileged children and planted trees.

They’ve organized fundraisings for people affected by floods and earthquakes with a kind of efficiency, transparency and reliability that the Chinese Red Cross could never stand a chance against.

In January 2020, the Empire responded faster than the Wuhan government in mobilizing and transporting medical supplies to desperate hospitals struck by COVID-19. They got hold of 200,000 masks and 150,000 gloves in less than 10 days and got them delivered to Wuhan within the first week of its official lockdown. Much of this is window dressing, but many are genuinely inspired by their idol’s call to become better people and more socially aware. Should the motive be interrogated when results are achieved?

Rubbles

The point is that there’s never one sweeping conclusion about Chinese celebrity fandom and there shouldn’t be one. The Empire is one multifaceted planet amongst countless others, each with its own ecosystem and biodiversity. Roaming around in these worlds, fans negotiate with and fluctuate between identities, constantly balancing standpoints and making value judgements.

In the bianzhi controversy, there are birdies taking more ambiguous positions and others who un-fan (脱粉) entirely out of disappointment. For them, this effectively shoved Yee into a long line of celebrities before him who are known as the “Rubble Celebrities” (塌房艺人).

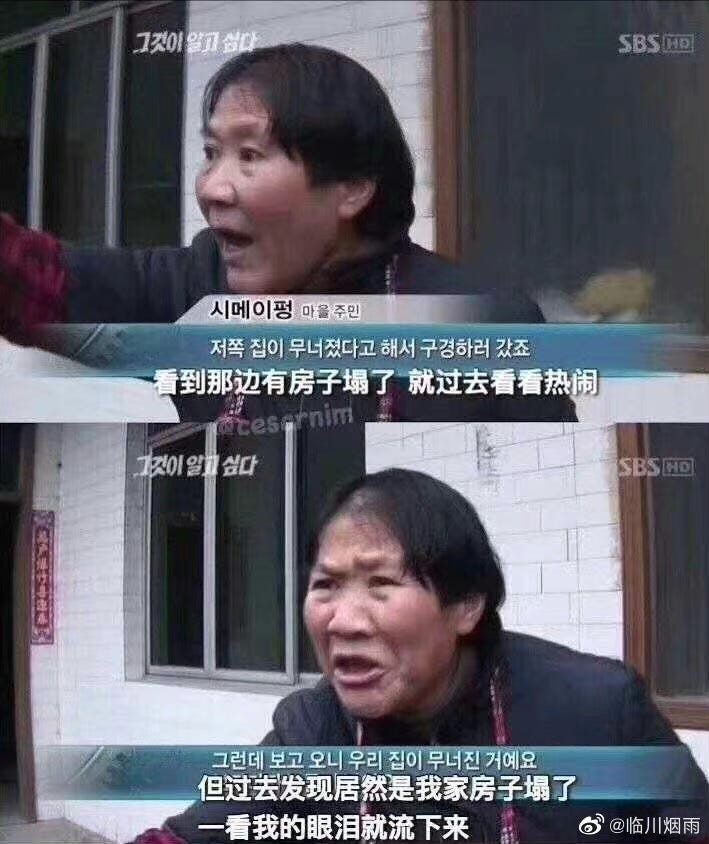

This is one of those fanquan sayings so bizarrely conceived that I actually remember the origin quite distinctly. It traces back to a decade-old sinkhole incident destroying several civilian houses. The televised coverage interviewed an elderly woman who returned to commotion around her neighbourhood from an outing. After loitering around and seeing that someone’s house fell into the sinkhole, she came to a belated realisation that it was none other than her own house.

Screenshots of her recount suddenly went viral around 2020, in a very Corn Song way. The phrase “house-falling” (塌房) was colloquialised in fanquan to describe the moment when a celebrity’s skeletons in the closet outpour. Their immaculate facade is swallowed by active faultlines that constitute the entertainment landscape and becomes rubble on the ground.

I’m further defining the term by what it’s not. First, house-falling differs from the English synonym of getting “cancelled”. The latter applies more to a situation where the public ostracises the celebrity for their misconduct, but house-falling is conjured up from the perspective of the fans.

Its etymological root connotes this: I, the fan, am personally connected to my idol. I am intimately attached to them to the point where I may subconsciously consider them a property of my possession. I am oblivious to the fragile materials that my house (the celebrity) is made of, and the sinkhole (the scandal) is an unforeseeable disaster that I am unprepared for.

It is also different to “idol shikkaku” (偶像失格), another denomination for disqualified idols and their inappropriate behaviours based on Osamu Dazai’s novel No Longer Human (Ningen Shikkaku) that’s popular in China. Like cancel culture, shikkaku is an extrinsic evaluation by third parties.

Meanwhile, house-falling is an embodied experience. Allow me to break the fourth wall here: my houses have fallen (too) many times to definitively argue that although the term might seem haphazard, it is integral to understand for fandom scholars. In a way, it’s all the struggles of being a fan crystallized in a single concept.

To name some of the most explosive house-fallings in the past, Kris Wu’s ousting as a rapist is up there. It crippled Weibo’s servers and millions un-fanned. The majority of his largely female fanbase asserts that sexual assault cannot be tolerated. I was one of them.

House-falling is every fan’s moment of disenchantment, the Nietzschean exclaim of “God is Dead” reverberating in our heads. “Whose house fell down? Oh, it’s mine” encapsulates, for me and many others, not only our dumbfoundedness when confronted with the truth. There is also the bitter acknowledgement of being ambushed, misled and betrayed. There’s disbelief, denial and an urge to question the plaintiffs in defence of my “house” like a muscle reflex. There’s an underlying sadness at the irreparable loss of something seemingly pristine. There’s self-loath at that sadness and denial because as a feminist, I cannot permit any lamentation for a criminal and yet it’s there. There’s anger at being fooled and the monstrosity of the crime committed, doubts about my taste, and sheer frustration at the time wasted as a fan and the fact that I regret it all.

Before I get carried away with this psychoanalytical detour, I want to conclude by saying that being a fan is so much more than feeling fanatic. Celebrity fans are daring, action-oriented, and politically sensitive. They could be swayed and biased but steadfast and principled elsewhere. Being a fan in China is being more akin to the electrical appliance sense of the word rather than the devoted, morally dubious follower. You’re in constant movement, switching sides and require a lot of energy. You’re noisy when something gets in the way and halts your movement.

In the next issue, I will be back with another example of how fans toggle between ethical positionings on an emotional rollercoaster. Let’s hear from female xiufen as they weigh their love and their own self.

See you then!

hello! I was reading your previous issues on fanquan. As someone who used to observe Chinese kpop fancircles for quite some time, I was stoked to see someone doing a deep dive on fanquan so I ended up reading all your entries. I never actually knew that 塌房 originated from That meme despite having seen it multiple times! I think that the house is used as a metaphor because of its associations with the domestic. The home is typically a place that brings comfort, which is why the phrase 我的快乐老家 is commonly used.