01. Extra Ordinary

the problem of celebrity self-expressions

Hi there. Welcome to another year with Active Faults!

When I started this project three years ago I did not know that Charli XCX would be on here too. Her piece, The Death of Cool, did its round on Twitter at the end of last year as people mocked that pop stars should stick to music lest their embarrassing run-on sentences, misplaced adverbs and bland opinions bust their image. It is ironically uncool to write about the death of cool when you’re trying so hard to look cool, condemning an industry that you find uncool. Rosalia has been posting exclusively in Spanish a range of content from handwritten music scores to recipes, which are significantly cooler in my opinion. By far the most exciting Substack buddies for me are Troye Sivan and Connor Franta, who, in my Youtuber phase circa 2014—2016, I shipped so devoutly that I read almost every Tronnor fan fic on Wattpad. This Substack probably wouldn’t even be here without them.

It is time, then, to comment on this correlation between celebrities and personal essays, or rather, this increasing need to reveal their inner worlds, to prove the existence of those worlds. Why? Why now? More importantly, what does it mean for the fan consumer and the community we’re in?

I cannot stop thinking about an anecdote that SEVENTEEN’s Mingyu shared in an interview. One of his fondest childhood memories is playing in the bathtub with his grandma, who would always poach out the pit of a softened peach for him to nibble on. The flesh would turn all mushy in his hands. DINO of SEVENTEEN recently talked about their rookie days, staying at a hotel in Hong Kong for their first ever award show and sharing an elevator with the assistants of another, much bigger star. The assistants were holding these weathered suitcases, plastered in luggage tags, stickers and fragile warnings that allude to world tours, limelight, fame, success. He thought maybe one day his suitcase would look like that too. And now it does.

Stories like these have always moved me, simply because of how mundane they are. How often they are hyperfocused on one particular detail, one fleeting moment in time that could be recounted by anyone and yet no one else at all. Intensely personal in the sense that the person disappears, and humanity begins. These details would read far less striking in an autobiography of an ordinary person as we anticipate hearing humanity from a complete stranger. But so much of a celebrity’s life is already aired, broadcasted, narrated, demystified, fact-checked, exposed and dehumanised to the point where idiosyncratic histories sound like foreign lands. You almost forget that they have memories too.

These glimmers of memories—truths—slip out of a celebrity from time to time. What they offer up is, unfortunately, an entirely different thing. This is the current tension behind celebrity accounts of life: what little else can be shared when so much of your life has already been consumed? And how much of what you gave out will go on to prop up an inauthentic persona instead of dismantling it?

In the case of Troye, I liked his first Substack piece that he posted two weeks ago. He talked about Hollywood’s ageist obsession with beautifying procedures, clapped back at an influencer who called him old and ugly, and was surprisingly honest about his own skincare anxiety. It struck me suddenly that when all the rest of us are hit with relentless advertisements and discourses that perpetuate toxic beauty standards, celebrities must get it a thousand times worse. They must hear it at every event they go to, in every club bathroom and every makeup trailer. Yet, this is the first time I’ve heard it being directly addressed with such clarity, by someone from the other side of the screen.

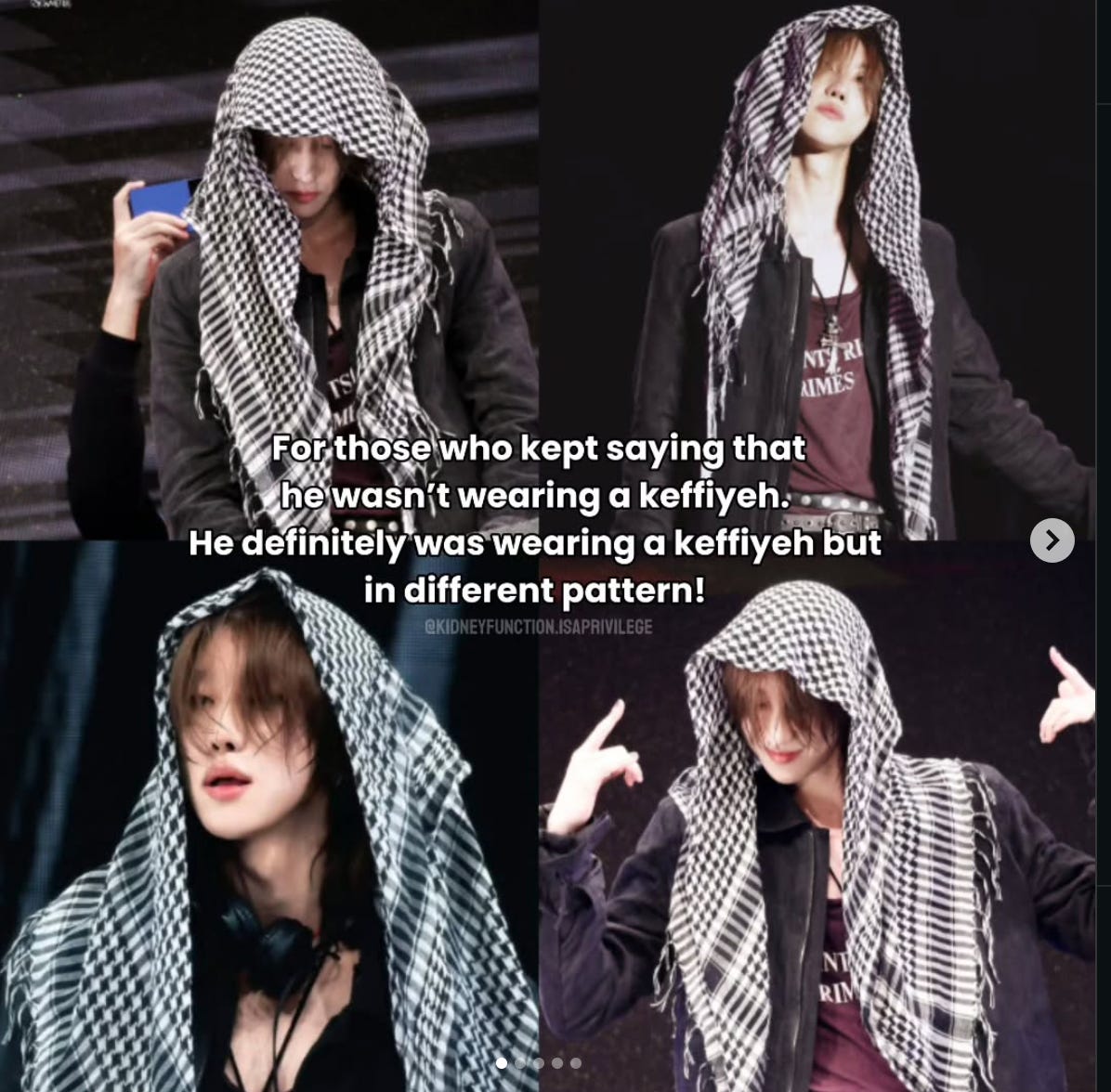

I suspect the Euroamerican celebrities’ essays are less headline-news than if personal accounts were to appear in K-Pop. There are hardly any taboos left in the Western media terrain. However, much about entertainer contracts, record label negotiations, the broadcasting world, as well as celebrity mental health issues and romantic relationships in Korea (and China) are still shrouded in darkness. These are what should be discussed and written about, but are brutally shut down instead. They must remain muddied waters, backroom manoeuvres, behind-the-scenes hush-hush that fans don’t get to know. The lack of transparency is supposed to breed rumours, conspiracies and hostility, which are food for traffic and fan wars that then guarantee loyalty and profit. It is supposed to render celebrities as perfect, passive creatures of beauty, ready to receive adoration and receive only. There is to be no output beyond performance, no takes on current affairs. Fans need to do all the hard work here: probing, guessing, interpreting, putting takes into idols’ mouths and inferring that they’re pro-Palestine or pro-LGBTQ, fanning, paying attention and paying for their success.

What becomes transparent instead are facets of the idol life that feel like a joke you shouldn’t laugh at. The (paywalled) docuseries format is gaining traction, as I’ve noted in the previous issue. The entirety of KATSEYE’s conception is filmed and televised, including the fierce competition between trainees and their conflicts. Groups like LE SSERAFIM, TWICE and SEVENTEEN are commissioning documentaries of their tours, album productions, and music festival appearances. So much is being offered up—rehearsals, long hours at the studios, dance practices, after-work drinks and late-night room services. It’s all meant to showcase their diligence and dedication, and the more you sit in it, the more you question the system itself. Watching their brand new, disorientingly-edited Disney+ documentary “Our Chapter”, I sometimes recoil at footage of SEVENTEEN’s medical emergencies, their mandated physiotherapies, their endless cycles of fasting and dieting. It makes the fans complicit in abuse disguised as discipline, who are powered by a ruthless curiosity that’s almost interchangeable with love.

For a group like SEVENTEEN who’s been live-streamed for the world to see since they were teenagers, they have gotten used to how invasive the cameras could be, how grotesque the fandom gaze could feel on their skin. How much money is involved in this exchange. It is clear that they have started to uphold tougher boundaries in recent years, become tight-lipped about their personal lives, keep intimate moments strictly off-camera and under-share. Stalking and violations of privacy are far too rampant for any self-expression to be safely presented. For neiyu celebrities, there is a much bigger risk of political trespass if they vocalise their opinions. The resulting landscape in (East) Asian entertainment is one of glamour and silence, like a lavish ball you watch through the window.

That being said, two people threw rocks at the glass last year. One of them is Cocona, a member of the K-Pop girl group “XG”, short for Extraordinary Girls. They made an unprecedented, jaw-dropping announcement claiming that they identify as a transmasculine non-binary person on their 20th birthday, and have undergone top surgery. They have always felt uncomfortable with their assigned gender at birth, and have always experienced difficulties with embracing their true self until now. They will continue their career performing as an idol as a part of XG.

You can imagine the instant ruckus in the community. Some fans were accepting, more were frazzled and nonplussed, if not angered and wounded. A fan writes emphatically on Xiaohongshu:

I’ve been a fan since 2023 and XG’s music has pushed me through many unbearable nights before Gaokao. I have always been the most moved by Cocona: they shaved their long hair in a music video and looked at the camera head-on like a wolf. They let us see that “a woman can live like this, undefined by our hair and our body, ready to pounce on stereotypes to become HERself”. That’s the core of XG’s group spirit: EXTRAORDINARY GIRLS and FEMALE EMPIRE. That’s the world we thought we were able to reach and actualise. And then they announce the surgery and their new pronouns.

XG once sang in the song “GRL GVNG”: “NEVER BE FIGHT WITH GIRL GANG”. The power of this lyric lies in the presumption that “GIRL” is a camp worth defending, a collective with strength and potential. We thought that Cocona’s bald head was intended to extend the boundaries of this camp—using their bravery, determination and action to declare that women can be tough, rebellious and unbounded by labels. In hindsight, it might have never been a broadening of our horizon after embracing the female identity, but a dress rehearsal for a total escape from femininity.

I’m not denying the legitimacy of nonbinary gender identifications. The real struggle is this: when an idol who endorses and promotes girl power finally achieves self-acceptance through de-feminisation, what is the message communicated to the girls who once believed that “girls can be powerful” through “her”? Is it that “you can beat gender stereotypes”? Or is it that “if you feel pained by it, just depart from this gender?”

I respect individual freedom. But idols never were and never will be just individuals. They are symbols, stories, a vessel to contain the projections of countless people. When this symbol transitions from “women can break free from restraints” over to “women can remove certain physical traits and use male pronouns to feel peace”, we lose not just an old persona of an idol, but more importantly what that persona promises: an alternative life as a woman.

Another post is even more nuanced, rebutting the argument that a top surgery is a given if someone identifies as nonbinary:

I am 100% for everyone becoming whatever gender they want, men, women, a Walmart plastic bag. But while being undefined, do you have to define “non-woman” by a removal of a feminine trait? If the physical body doesn’t represent “me”, then why is surgery necessary?

Queerness and nonbinarism represents a freedom of the soul that’s beyond any physical traits. But a top removal surgery is acknowledging that breasts have an unseverable, ontological relationship with femininity. It is almost saying that to become a “non-woman” and a “more authentic self”, you have to first deny the signifiers that constitute the female body. Is this really liberation, or disgust and self-deprecation? Is it not announcing that a part of my body is hindering me?

Breasts shouldn’t be idolized by men nor hated by women. The real victory is not “removal in order to self-actualise”, but “acceptance through desymbolisation” [...] Rendering “breast-cutting” as a flag-waving, ceremonial act will achieve the opposite of attaching too heavy of a symbolic meaning to a mere physical trait, converting it from a bodily organ that needs to be disenchanted into a label that must be eradicated. Comparatively speaking, I haven’t seen many trans women insisting that they remove their Adam’s apple or their penises. Our society’s disciplining of the female body runs so deep that even the resistance to it has to be scarred.

The life-force of transgender studies and queer theories lie with its diversity and uncertainties, in its permission of everything existing in the “in-between”, “outside of”, and “wavering” states.

I’m not against surgeries and they could very well be a form of redemption for someone who feels restricted. But I also don’t like this tendency to put a choice on a pedestal and turn it into a spiritual war banner. Queerness is supposed to be a practice of tenderness, encouraging you to look for yourself instead of participating in a competition of who’s “more brave”, or who’s more “assertive” and merciless when it comes to transitions. It should be about creating a world where breasts and bodies are no longer important. Doesn’t matter whether you have it or not, however it looks like—it does not stop you from becoming anyone.1

Other posts pick up different threads in the discourse, the fact that they’re “too young” and too impressionable to make such a paramount decision that’s incredibly public to a fan base filled with minors, the fact that it is suspected Cocona was deeply influenced and controlled by a male producer. Another camp says that you should only care about the music, while some female fans particularly dislike the “he” pronoun more than the “they”.

I, for one, am torn. I want to stand in solidarity with the first nonbinary figure in K-pop whose honesty is refreshing and admirable. At the same time, I also see why this decision can feel like a betrayal to XG’s most diehard followers. It can feel like my idol has abandoned me to fend for myself in the patriarchal structure, after they approached the gender that wields power and the whole group has lured me into an illusion of freedom. I would feel cheated and deceived, both emotionally and financially. I cannot emphasise enough that celebrities are commodified. There is simply so much money at stake in the idol industry that they become bound to their fandoms contractually. Yes, they are individuals with basic human rights and they owe me nothing, but they also owe us a lot, too much, their whole career trajectory. We cannot separate (East Asian) celebrity self-expression from the narratives it is selling and the revenue it is generating.

Cocona probably would’ve secured more support if XG wasn’t founded entirely on the concept of “girl power”, “female empire” and the grammatical fiasco of a statement “never be fight with the girl gang”. Likewise, people would probably be more impressed if Cocona started with a clean slate, left the group and became a solo, nonbinary artist. The fact that they stayed in the group, continued to play by the rules of the industry after a heroic attempt to disrupt it, and continued to profit off of feminist messagings while claiming they are distressed by femininity is the crux of fan anger. It’s not queerness that’s irking everyone, but this inconsistency that looks like hypocrisy and trivialisation.

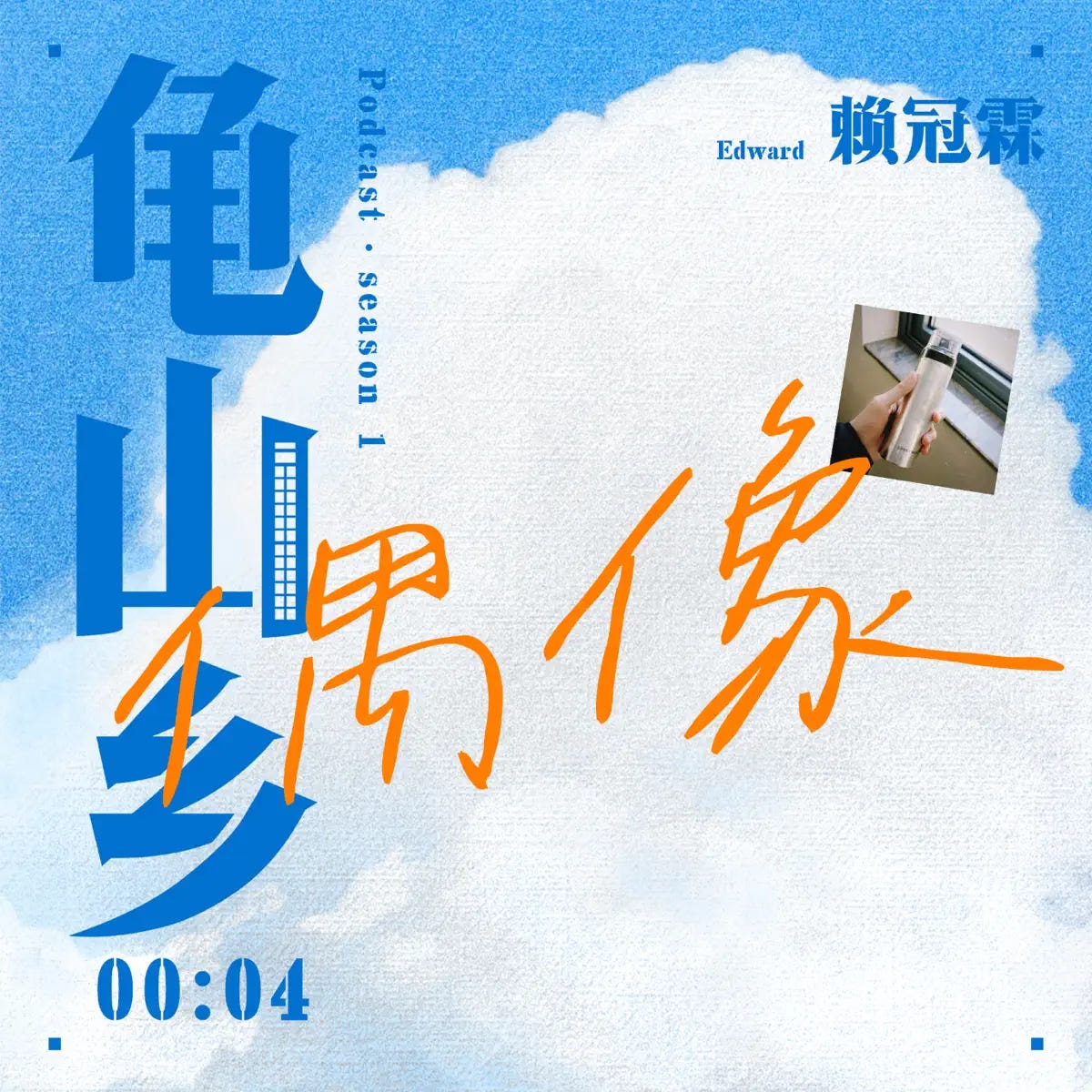

I was equally surprised to find that Lai Guanlin, a former member of the K-pop boy group WANNAONE, has left the industry and started a podcast. Last I heard of the Taiwanese idol was when he got papped spitting on the street and having a girlfriend. He tried to (perfunctorily) apologise on Weibo and his fans were less than accommodating of his attitude, especially after years of pretending to enjoy his half-hearted acting or singing. On the cusp of his industry exit, he revealed in an interview that he never identified with the profession at all, was never comfortable as a celebrity. Despite, might I add, having gotten into one of the most successful idol groups of all time through his own hard work in the xuanxiu “Produce 101”, and earning millions of cash and followers. You can imagine the shock and disillusionment of his fan base, as well as their consensus to let him fade out.

Yet, alas, he became another dude behind a microphone. “龟山乡” is the neighbourhood he grew up in Taipei, with which he named his programme. The inaugural episode was a bit of an unstructured ramble, but it had him talking about his home town, the infrastructures of Taiwan’s suburbs, his negotiations with his split identities and a prickly, slippery sense of belonging. He also mentioned his discomfort with the entertainment industry, how everyone is so far removed from reality that he doesn’t recall ever doing hotel check-ins by himself. All of which are the kinds of opinions and perspectives that neiyu fandom sorely needs.

However, there are obvious efforts to de-celebritise himself through the use of laymen language, which, not unlike Charli’s essay, ended up feeling too forced. When he addressed his listeners who will obviously be his fans from his idol days, he used the plural of “you” instead of naming them outright, just so that nothing sounds like fan-service. He framed himself as a content creator, a director and a “北漂” person, a term specifically referring to migrant workers who left their lower-tiered cities to seek jobs in Beijing. That’s not his tax bracket to claim. He name-drops and commends another popular podcast on the platform run by a non-entertainer, just to blend in with this crowd.

Again, I’m not dismissing celebrity self-expressions altogether as performative whinings of a privileged bunch. My point is that their contexts and impacts shouldn’t go unnoticed. They must be contested while we bear in mind the system they gave rise to, even and especially as they make moves to disrupt it. Engagement farming and profit maximisation are intentions concomitant with celebrity self-expressions, which makes them a means to an end, even when the current trend is to condemn than to praise. They are still appealing to their fans when they hate on their surroundings that brought the fans in.

Of course, that’s not to say that I wasn’t moved by some of the stories told. Lai Guanlin talked about how many boarding pass stubs he has of the same redeye flight from Beijing to Taipei. Hanging on my bathroom wall is a picture frame filled with boarding pass stubs of the same Beijing—London flight I’ve taken across a decade. His accent is now a mix of Taiwanese, Korean, Beijingnese and celebrit-ese, his Mandarin filled with media-training-filler-words and a hint of coastlines, Seoul snow and night-market fishballs. My accent has always sounded like an international school corridor, a four-legged Euroamerican mongrel flapping around in the Hudson and the Thames. I can interrogate and contest and find their expressions inconsistent, but I will inevitably connect and relate and empathise as a fan of theirs or of someone else, because I too am a player in the game. When I hear MINGYU talking about his grandma I think of my grandma with whom I regret not sharing a peach. When I hear DINO talking about suitcases I think of purchasing my suitcase (in Hong Kong of all places) a month before I was due to move away and my crippling teenage anxiety. Being a fan means that my memories will always bounce off of theirs.

I loved this paragraph from Toni Morrison’s essay “The Site of Memory”:

The act of imagination is always bound up with memory. They straightened out the Mississippi River in places to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, what valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory - what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our ‘flooding’.

To hear personal accounts of celebrities is to imagine their lives as an attempt to remember ours. In doing so, we understand our places in the world, our ways of loving, and how we can make use of our time here. It is just essential that we ask some questions too.

All emphasis in the quoted paragraphs are my own.

celebrit-ese could be worth a whole edition!