Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Happy Pride! In the true spirit of this month, the following issues will try to tackle what I think is the hardest (and queerest) to pin down in fanquan, a driving force and backbone of the entertainment industry that, at the same time, defies categorisation and rationalisation.

Let’s talk about the shippers or more specifically, the male-male “couple fans” (CP粉), who fantasize about a romantic relationship between two men. They are and have always been a kind of awkward third wheel in between the conventional fan-celebrity relations in Chinese entertainment. A “Your Friend Steve” presence that’s almost seen as intrusive and doesn’t sit well with neither.

Steve has entered the chat.

Enclosure

I was already late to the scene when I first discovered danmei (耽美), male-male homoerotic content. It was introduced to Chinese audiences in the late 90s through Japanese manga, before quickly getting traction and evolving into a prominent subculture. The word itself is onomatopoeic with its Japanese original “tanbi”, meaning the pursuit of and indulgence in beauty. “Tanbi” is also a direct translation of the 19th-century art movement aestheticism. Since then, it has been an almost exclusively female-dominated genre, where a euphemism for danmei is actually “female-oriented” content (女性向). And it’s been exactly that: danmei in China is consumed, produced and circulated by women to celebrate the most aesthetically pleasing romance between idealised males.

Chinese feminist scholars in the past decade or so saw the importance of studying danmei as a feminine subversive genre, a space where women can gather to collectively envision a perfect partnership without the constraints of heteronormativity. The danmei world provides an insulated context where sex is had for sex’s sake. It is somehow purer than a traditional heterosexual relationship, having nothing to do with marriage, pregnancy, childbearing and hence social duties. Through the consumption and composition of danmei, women can express their emotional needs without being reminded of their own realities, safely longing from afar.

You can see why, then, danmei is popular amongst female fans of male celebrities. The gist is similar: mediated expressions of desire and love. Wanting confirmation that I am loved and I am capable of loving (fan-celebrity relationship) or that love exists and I am capable of loving (shipping).

Different to “唯粉” (solo stans) who solely fan over one celebrity and assume different psychological bearings towards them, male-male couple fans (hereafter CPF) are fanning over the coupling of two celebrities. They actively imagine, speculate (or, at times, extrapolate) a romantic relationship between attractive men, basing their fantasies on real-life interactions. They discuss the men’s on-screen chemistry, hope for more evidence to pop up that supports their theory, and appreciate the beauty of their bond.

That’s not the motto everybody follows. CPF have been at war with 唯粉 for as long as I can remember. AO3’s demise in China was, essentially, the unfortunate result of a battle between the solo stans of Xiao Zhan and the CPF of Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo. CPF are criticised as delusional, disloyal, and inauthentic fans of the celebrity. CPF are never devoted enough because they admire two deities instead of the One True God. Ultimately, their belief in the celebrity’s relationship with another man is an interception of the exclusive bond between the stan and the artist.

Thus, CPF are trained to practice their fanning with a ground rule: 圈地自萌, meaning “shipping two people on an enclosed patch of land”. Shipper fandoms form enclosures to ward off hostile gazes and ship in privacy, with the help of social media platform features like super topics.

CPF are told to keep their identity a secret and refrain from mentioning the other half of the pairing in one’s content. Enclosure laws are enforced to such an extent that the celebrities’ full names cannot be properly uttered in the couple’s super-topic: they have to be censored or swapped to code names, euphemisms, homonyms or emojis.

This is to prevent 唯粉 from searching the celebrity’s name and seeing shippers’ posts on the Plaza, triggering discontent or clashes between the groups. The reasoning behind solo stans’ intervention is that male homosexuality is still viewed as a public indecency by society. No male celebrities should be seen in that light, let alone associated with another man which could lead to a career downfall. CPF should lay low for the sake of protecting the celebrities, ending up being tongue-tied and excommunicated from the larger fandom.

Making a Name

Chains around CPF lead to several kinds of rebellions.

Firstly, aggressive spending habits. To rebut 唯粉 accusations that CPF are not real fans, the latter use their purchasing power to prove otherwise, be it buying albums, magazines, sponsored products or merch in bulk, or committing to large-scale charity projects in the name of both celebrities.

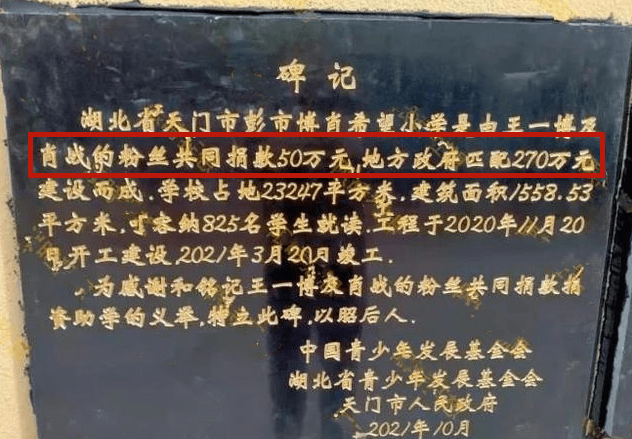

In 2019, a mega CPF of Xiao Zhan/Wang Yibo crowdfunded 500,000 RMB and donated the money to China Youth Development Foundation for the construction of a school in Hubei province, subsequently naming it “BoXiao” School of Hope. Pictures of the school’s signpost and memorial plaque went viral online in 2021 after its completion, drawing the attention of the provincial government which swiftly ordered a removal.

Many supported the government’s decision, arguing that “toxic fandom culture” should not invade the “sacred lands of education”. CPF who chipped in the crowdfunding demanded a refund of their money, protesting against the blatant “contract breach” on the government’s half, who previously agreed to grant naming rights to the fans. They want visibility and justification of their shipper identity, as well as recognition for their good deed. Boxiao fans used their comments-controlling and mass-reporting tactics like seasoned veterans, sending over 1,100 complaints to the government’s website (using a standardized template drafted by a mega fan, you know the drill). It reads:

[...]As a fan benefactor I have nothing but passion to help the future leaders of our beloved country to complete their studies in better conditions with my meagre efforts. The decision [to revoke naming rights] paid no consideration to the general public’s passion for charity and social welfare. This is a kind of “an nao fen pei” (distribution according to who is the noisiest or causes the most disturbance, meaning the government only catered towards the ones who complained the loudest) after some unrelated persons’ picking of quarrels - is it not a form of sloppy governance?

Quoting ex-premier Li Keqiang’s speeches and adopting political lingos did not help. CPF remains unrecognised, and they seemed to insinuate that the removal was due to protests of solo stans. Nonetheless, this did not prevent them from successfully funding and naming a dozen other charity projects across rural China, including roads, bridges, and street lamps.

(screams at the top of my lungs)

At other times, they legitimise their shipping using pro-LGBT discourses. An outdated term for danmei fans, 腐女, takes after the Japanese word “fujoshi”, meaning “rotten girls” who are too ruined to be married out for loving male homosexuality. The fear of being seen as rotten lingers, and allies CPF with the subjects of their consumption: the supposedly gay celebrities. Their pride in shipping is viewed, perhaps subconsciously, as their gesture to stand in solidarity with the male homosexual community. Although rarely, CPF can problematically borrow the narratives from LGBTQ+ movements to make a point, that their shipping is for a greater cause of gay rights awareness raising. That’s not entirely untrue, but in reality, danmei is an obvious over-romanticization of male homosexuality that no such equivalents should be made.

What’s even more bewildering is an emergent style of expression noteworthy amongst CPF and fanquan as a whole, the “toilet talk” (厕). A typical toilet post normally contains dark humour articulated through amoralistic, transgressive and sometimes deliberately revolting rhetoric. Dedicated Weibo accounts are made by toilet talk enthusiasts who post DM submissions from followers, as many as in the 6 digits.

CPF’s toilet talk about their ship is characterised by incredibly NSFW and hypersexualised imageries, memes that can be used as daican, and all sorts of scenarios regarding the pairing that would be seen as transgressive and corrupt or degenerate.

I see a connection between toilet talk and “insanity talk” (发疯文学), a concurrent online vernacular that is just, illogical gibberish for humorous effects. It’s modern-day Dadaism, a way of venting through nonsense. Insanity talk was particularly prominent around the second half of 2022, when COVID-19 policies drove everyone into dead-ends.

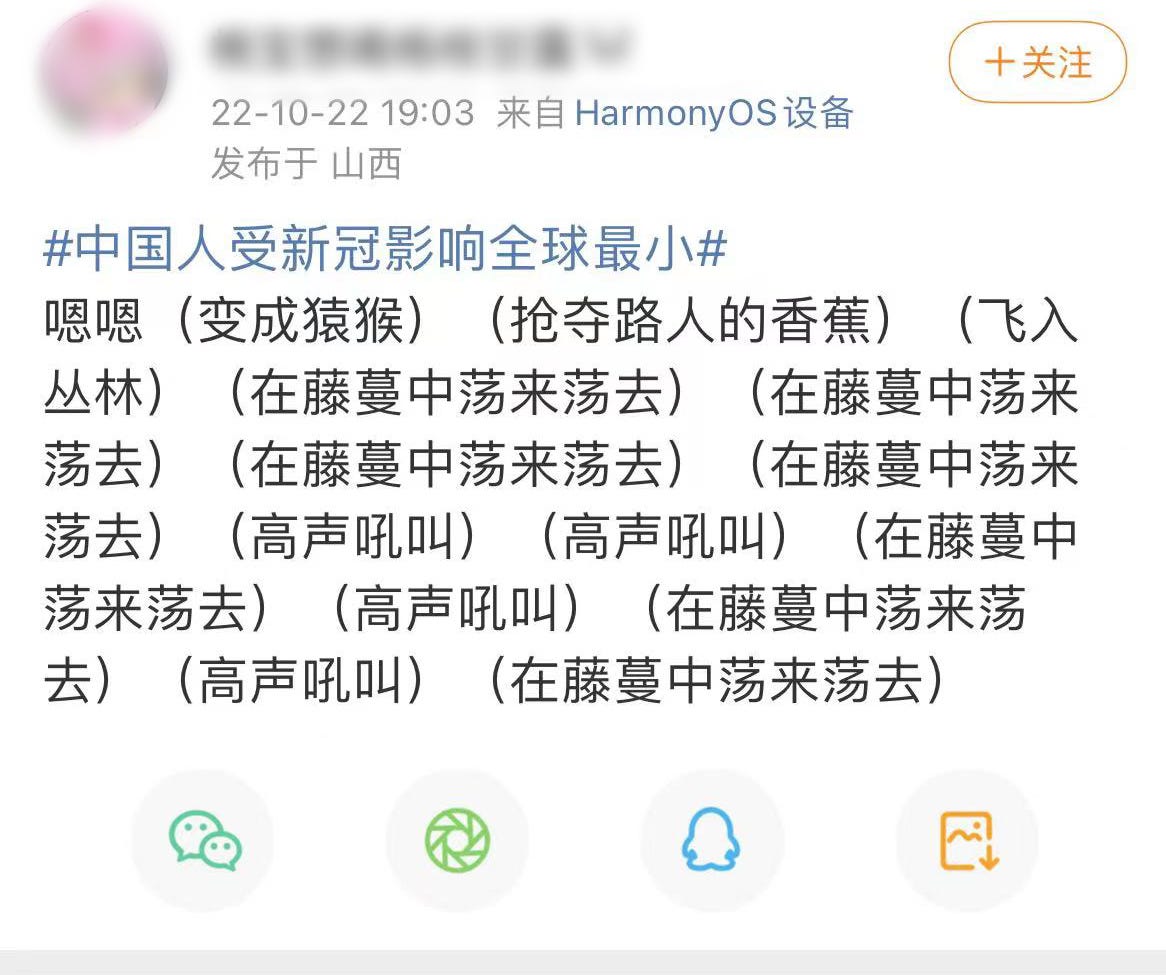

A hashtag on Weibo started to trend in late October that year, which reads: #Globally, Chinese people are the least affected by the COVID-19 pandemic# (#中国人受新冠影响全球最小#) Within minutes, the hashtag was bombarded by netizens’ insanity talk. Here’s one of my favourites:

#Globally, Chinese people are the least affected by the COVID-19 pandemic#

Sure sure (becomes an ape) (snatches a banana from a passerby) (flies into the woods) (swings around the vines) (swings around the vines) (swings around the vines) (screams at the top of my lungs) (screams at the top of my lungs) (swings around the vines) (screams at the top of my lungs) (swings around the vines)

And of course, this hashtag quickly got taken down afterwards.

In a country where words are abducted by agenda, it’s unsurprising to see that language has to be eroded into silence on a piece of white paper, or completely incomprehensible sounds, in order to communicate the truth.

CPF uses toilet talk to fantasize however they want; Fanquan uses toilet talk out of frustration at being disciplined to behave, while still being represented as toxic; The public uses insanity talk as an opportunity to let out their dissatisfaction.

In the next issue, we’re diving into a crucial aspect of every CPF’s image-making: consuming and writing fan fiction. Fan fiction is integral to a CPF community - sometimes more so than the actual celebrities themselves. It helps the fan to re-examine and rebuild the identity of the self, their place in the fandom, understanding of other fans around them as well as the celebrities. More importantly, it’s a “F*ck you, I will be Steve and I’ll do whatever I want”.

See you then!

*Issue cover: BTS fanart by @ plainnt

Holy cow. You just explained stuff I hadnt been able to comprehend.

My background is about 30 years in US film and tv production, as a producer and writer. I will be 75 in April. And Ive never ever seen anything like what happens among fans in China. I mean sure, US stars occasionally attract crazed stalkers -- but thats rare and not at all the same thing.

Anyway.

I learned all kinds of new words and concepts like Stan, shipping, and fanfic.

Anyway, you should compile your essays into a book.

Im still into watching Chinese productions as a way to comprehend Chinese culture. Fandom is a sociological phenomenon. Thx for being on substack.