Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Fandom Exile’s incredible piece on “Tayronto” inspired this issue.

Reflecting on the “celebrification of cityscapes”, I’m reminded of China's post-pandemic boom of music festivals and how that industry contributes to tourism-backed provincial economies.

Today, let me talk you through my 48 hours in Shenyang.

I’ve been listening to Guo Ding, the indie singer-songwriter, since his 2016 album “The Silence Star Stone” (飞行器的执行周期). Notorious for his inactivity on social media, aversion to concerts, and sparse discography since this six-time Golden Melody Award nominee of an album, the best place to catch him is…a music festival. He seems to really like those. After 7 years of unfortunate clashes in life scheduling and missed opportunities, something finally aligned this past August. I managed to secure two tickets for the Rose Festival hosted in my beloved Dongbei, in Shenyang of the Liaoning province, where Guo is in the lineup.

Now a word about Shenyang. It is one of your run-of-the-mill “二线城市”, Tier 2 cities, where urban planning efforts can’t catch up with its grandiose vision of modernisation. The place feels like it’s out of breath, racing to look suave and spotless and glassy sleek against its past cringy self, and failing to conceal the stains under its sweaty pits. High-rises litter the skyline like it doesn’t cost a dime to build them, and looking down you’d find lopsided pavements cracking under the weight of the crisscrossing share-bikes. Cars honk in endless, winding traffic. The new builds look ghostly and unlived. The older parts of the town look grimy and exasperated. And that makes it a prime location for a music festival.

If you go on Damai (China’s Ticketmaster) and browse for music festivals nowadays, you’d find that most are located not in Tier 1 megalopolis like the BSG (Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou), but less well-known towns in heavily residential provinces. In a report published by 中国音乐财经, statistics from the past four years show that only a meagre 66 festivals took place in Tier 1 cities compared to 100 in Tier 2 and 111 in Tier 3. More numbers for you to ponder:

159 festivals took place in the so-called 新一线城市, the New Tier 1 Cities, nascent metropoles like Chengdu, Chongqing, Hangzhou, Wuhan, Xi’An, Nanjing and more.

124 festivals took place in Tier 4-5 towns and villages.

Provinces in the highly commercialised Eastern regions hosted the most amount of festivals (221), but the number is on the rise for the remote and less urbanised West, including Xinjiang UAR (73 festivals in 2023 alone).

And here’s why. Among all of the sponsors and organisers of music festivals in 2023, “provincial governments, cultural-tourism conglomerates, and provincial city construction investment group companies” (地方政府、文旅集团、地方城投公司) significantly outnumber other parties. Let me translate this: local authorities are instrumentalising entertainment events to ease off their crippling debt. There’s an ever-growing imperative to attract live show junkies from out of town because they could also be tourist sights visitors, restaurant and bar-goers, and perhaps most importantly, social media users on the verge of a viral post that could change literally everything. They hold the town’s fate in their smartphone-holding hands, because this is the era of pan-celebrities. Anyone could gain a million views for anything.

You could almost taste the electrified air of competition. Dongbei, the former industrial stronghold in shining coats of fur, is now a frail beast that crawls to win the hospitality war. At the Rose Festival, food stalls brought the renowned local snack “chicken scraps” (鸡架) to the fans, alongside “rotatoes”, Dongbei veggie wraps and more. The health and safety announcements were made in a comedic Dongbei accent with dialectic words and phrases, like a skit. Advertisements of what else Shenyang has to offer were everywhere to be seen: we found out that many food stalls have a permanent base in the town’s night market street. After the show wrapped, there were free shuttles to take the crowd into the city centre from the suburban football park where the festival was hosted. There were rentable bean bags, picnic blankets, chargers, umbrellas, raincoats and free sanitary products. I would imagine such “peripheral services” provided at bigger music festival brands, like the Strawberry or the Xiami, are even more comprehensive.

Here’s the deep lore behind chicken scraps: it had its viral moment back in 2021 thanks to the CCTV5 sports journalist Wang Bingbing, who first went viral for being very pretty. A Dongbei native, Wang chuckled at the word “aeroplane frame” (机架) because it’s homonymic to the snack in one of her interviews. Word of mouth about the delicacy spread across the country. Fans of hers rushed to Dongbei to try it. In the following months, the Beijing Winter Olympics rolled around and the snowy North was all the hype. The authorities began to generate tourism campaigns, involving viral foods and influencers as part of its appeal, and push for an Ice Crazed Winter to ride on the high tide of it all. I’m tracing the genealogy like this just to prove a point, that pan-celebrities, fandom, social media, tourism, culture, politics and sports can be intimately interconnected. The chain reaction ripples and encompasses.

All across the country, cities like Shenyang are lurking in the woods, ready to pounce. They are eyeing their moment to catch onto the tail of minuscule virality, and completely rebrand the cityscape based on it. Like boarding a flight while it's charging ahead at full speed, 10,000 feet above the ground. I’m naming a few more towns and key words here if you want to delve into them as case studies. Zi’Bo from Shandong, and the barbequed skewers. Harbin, in Heilongjiang, and the hotsprings and spas. Liuzhou, in Guangxi, and its luosifen. Dali, in Yunnan, for the indie bars and vibes. Xinjiang, for how much it resembles Mars (the planet). As makeovers ensue, celebrities and entertainment are embedded in the fabrics: the Yang Ying cafe in Dali where she had a photoshoot that her fans then flock to, Zhao Liying and the flower crown, and so, so much more.

I fear that entertainment will be subjected to further shunning in 2025, because it is fundamentally an industry that serves up emotional value to its consumers (情绪价值). I personally loathe the buzzword but here it could be apt. People are splurging on experiences and instantaneous gratifications instead of houses and marriages, and They don’t want that. People go to concerts and festivals, travel out of town for them and make a holiday out of it, and eat and try chicken scraps and then eat a bit more. So much uncertainty lies ahead and we must burrow our heads in senses of elation that are tangible and immediate.

In some ways, entertainment is the sore thumb that represents everything They don’t want us to look towards. At day 1 of the Rose which I attended, most of the bands gave a shout-out to Dongbei as the land of “rebellious spirits” and unkempt demeanours. The real rock-n-roll lot. One of them even made a slight jab at the top players of the festival game (probably Strawberry) for restricting “what artists can say on stage”. My favourite line of the night came from the band Reflector (反光镜) who said “If we can’t criticise, we must sing and praise” (如果不能谴责,我们就去歌唱). What a statement to make. The lineup of Day 2 featured a lot more Metrics Idols (流量艺人), who I imagine would be a lot less vocal but nonetheless still “radical”, because towards whom young women gravitate and divert their savings.

In the crowd, I spotted people wearing security guard uniforms and pseudo-policemen uniforms as their costumes. They blended right in with the actual guards that were on the premises.

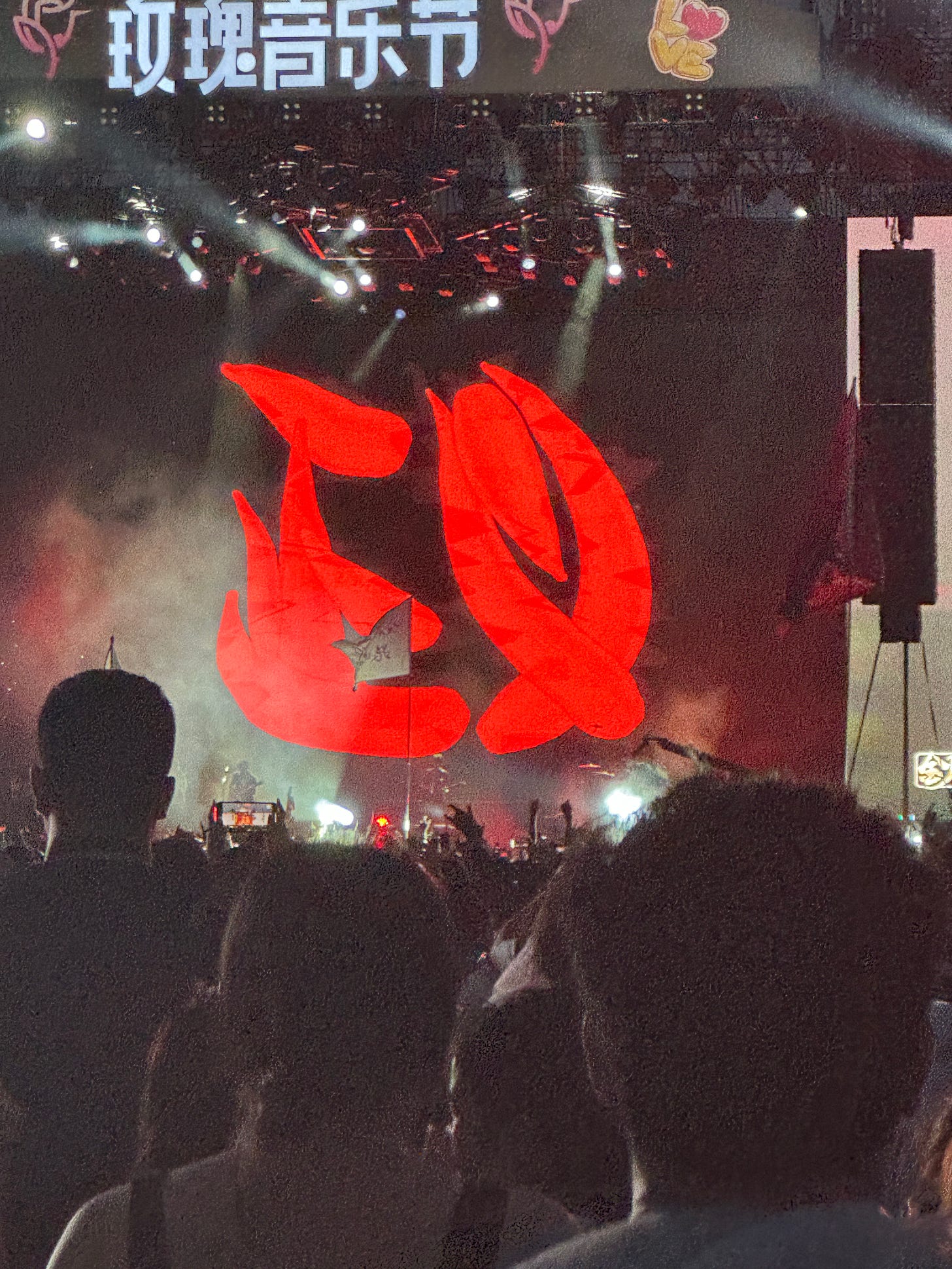

People brought buckets, metal bowls and drumsticks to clank and clatter to the music. In the pit, there were conga lines and dance battle circles. There was a flag, coloured in a deep crimson red, that said “make Dongbei prosperous again” (振兴东北). You can’t mistake these for anything else. These are acts to deconstruct institutional symbols of violence and surveillance; exploit cacophony to express the unsayable like holding up a piece of white paper to protest the unprotestable; mobilise and let loose and rejoice when the explicit order is to do otherwise. It is resistance even though the people won’t necessarily name it as such and They won’t necessarily recognise.

But maybe They do. Did you know that most music festivals in China are completely dry? My honeydew melon soda drink was non-alcoholic. I had to stomach my bad luck and get soaked by torrential rain thrice while functioning on pure adrenaline. They know the power a crowd holds, especially if fuelled by music that talks of revolutions and intoxicating substances are involved. Maybe festivals are too big of a risk, and They’re coming for it next.

When FloruitShow, an ex-Big Band contestant was performing a song with Buddhist messagings in the downpours, a guy next to me made prayer hands to the artists, or at the rain, or even some form of God, asking for God-knows-what: better weather, the right to criticise and not just sing, a new age.

This is so interesting! I’ve been to a few music festivals in Taiwan and there are some similarities with what you described, e.g. smaller city governments providing better support for festivals, and political protest signage in the crowd. While I don’t think the festivals completely restrict what people are allowed to say here, I have noticed that attendees are selective about which bands they choose to wave political flags for (for example, you won’t see any independence flags when mainstream bands popular across the strait like 告五人 are performing). I’ve wondered in the past if the festival organizers/band staff have something to do with this, but can’t say for sure!