15. Play Ping Pong Until You Don't Have To

Chinese Celeb-Athletes, fanquan-isation of sports and what happened at Paris

Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Out of all the games in the Paris Olympics, I’ve kept up with speed climbing more diligently than I did with anything else. Not that I’m a hardcore fan of it, or that I’ve kept up with any other matches - I’ve got the athleticism of a stick of tanghulu - but because it’s always on during dinner time, and our dining area has a TV.

In the men’s finals, I caught one glimpse of the Chinese contestant and knew that he’d go viral. He’d turn into the next Sun Yang (swimming) or Zhang Jike (table tennis) and become the nation’s next hot athlete, the freshest “cyber husband” who would then sneak his way into entertainment. He did.

Today, let’s talk about Chinese athletes, their fans and the so-called fanquan-isation of sports.

I don’t know enough about sports, but it turns out that I do know neiyu. A search on Xiaohongshu and Weibo gave me hundreds if not thousands of posts already thirsting after Wu Peng’s muscles, his record-breaking speed-climbing performance and his boyish but stoic face. He was anointed by netizens as a “少年将军”, “teenage army general”, for his adamant gaze of steely determination before he gets on the wall. Others call him a protagonist in a “hot-blood anime” (热血漫男主), highlighting his resemblance to the leads of sport-centric, school varsity-themed anime classics like “Free!” Or “Haikyu!!”. Although the silver medal he eventually bagged was a “disappointment” to him, he won the gold in other ways.

Xiaohongshu immediately caught on. He was part of the platform’s lineup of Olympian live streams and got over 250K views. Provincial tourism bureaus, the latest entrants in the social media traffic war were a close second. Their “整活儿” (show-making, a new slang for desperate content creation with the sole purpose of going viral) consisted of photoshopping Wu Peng onto famous mountains in their region to promote the sights. Dozens of reels surface where a horribly cropped-out Wu comically climbs the famed peaks of Tai Shan (Shandong province) or Huang Shan (Anhui province) in less than 4 seconds.

Fans waited in the airport of Shaoyang, Hunan to see him make a triumphant return to his hometown. When he paid a visit to his Alma Mater, his teachers and juniors asked for autographs. I won’t be surprised if he starts to appear on reality shows or becomes a brand ambassador who does sponsored ads.

That is, after all, a common route for Chinese athletes to go down. His fellow Paris Olympian Zhang Boheng attended three live streams on Xiaohongshu, Douyin and Kuaishou, a result of his virality over a GIF of him looking distraught after a major slip-up in the game. It was apparently the epitome of “脆弱美” (vulnerability as beauty). See how my recipe for success for neiyu men is fool-proof again? It’s all about a persona that tastefully balances power and vulnerability, sanctity and profanity. Athletes hit that sweet spot, bull's eye. They will seek every opportunity to monetise it.

This Vista article covers the side quests of this year’s Olympians in more detail, so I won’t go into it further. My point here is this: Chinese athletes are an aberrant breed of celebrities. On the one hand, their fame translates into a similar set of phenomena as in the case of a traditional celebrity: fans, business deals, air time. On the other hand, the stakes are so, so much higher when you’re representing your state while millions watch your every move, live, all over the globe. Local newspapers termed Wu Peng a hero and the authorities are considering awarding him an official Medal of Meritorious Deeds. When it comes to top athletes in our strongest fields like diving or table tennis, the likes of Quan Hongchan and Wang Chuqin are getting bounty from the top with every Gold they earn. Deservedly, perhaps, but at what cost?

One of the best descriptions of modern-day stardom I heard this year is from the Tortured Poet herself, in the song “Clara Bow”: it’s Hell on Earth to be heavenly. I’d argue that’s quite literal for Chinese celebrity athletes. You can shoot to extraordinary heights overnight with one GIF, one line in an interview or one match. You can plunge into a complete information blackout if you resist the system. Surveillance and supervision over athletes are justified if not encouraged by the public, as they are subconsciously considered the instruments and properties of the government. They slip into a pseudo-authoritative position because they are to be respected as soldiers in wars.

Sports fanquan is lent that authority and legitimacy. It is a lot more acceptable to fan over an athlete than an idol. My WeChat friends can post their table-tennis-themed manicure patterns, fly to Paris to watch all the matches, wave flags, scream cheer, paint your face and wear athlete “同款” from ANTA without hesitation or being called crazy. Try doing the same for an idol group, or just go to more than one concert stop in a tour. You’d be “jobless”, “toxic” and “pathologically obsessed”.

I wonder if - No. I don’t wonder and I know: sport is gender-coded to be masculine and hence lawful. In places like China, that legality is reinforced twofold by propaganda associating athleticism with national pride. Female sports fans can exist and behave in ways otherwise considered “irrational” in a different context, like praising the physical appearances of (male) athletes or calling them husbands. That “fanaticism” can frame itself as nationalism and phallocentrism, and borrow that stamp of approval in a society that upholds both. It becomes sad when some use it to feel superior against other female fans of idols.

The fanquanisation of sports is a nationalism project. It is now actively proliferated by the top to stir up support for the glorious party that raised these warriors fighting for the country’s honour. I’m old enough to remember the days when the prevalent discourse was deterring athletes from excessive exposure in media and entertainment. They should avoid “抛头露面” and focus on their career. A drastic shift has occurred in recent years. I see how this is now reversed: they are pushed into the limelight by participating in live streams, gracing magazine covers, selling suitcases on Taobao, coming out as a Swiftie and making their Olympic victory post using lyrics of Long Live and responding to memes of themselves. They ride on trends and celebritise themselves to garner attention that indirectly profits the state.

That’s why when sports fanquan is being accused of toxicity this year, people are talking back: you made it happen. In the table tennis finals for women’s singles this year, a civil war occurred where contestants Chen Meng and Sun Yingsha, both Chinese, went head to head with each other. Chen won the Gold when the overwhelming majority of the fans present at the game were supporting Sun, cheering on Sun, stomping the floor and giving out freebies. It is rumoured that they boo-ed when Chen was on the podium.

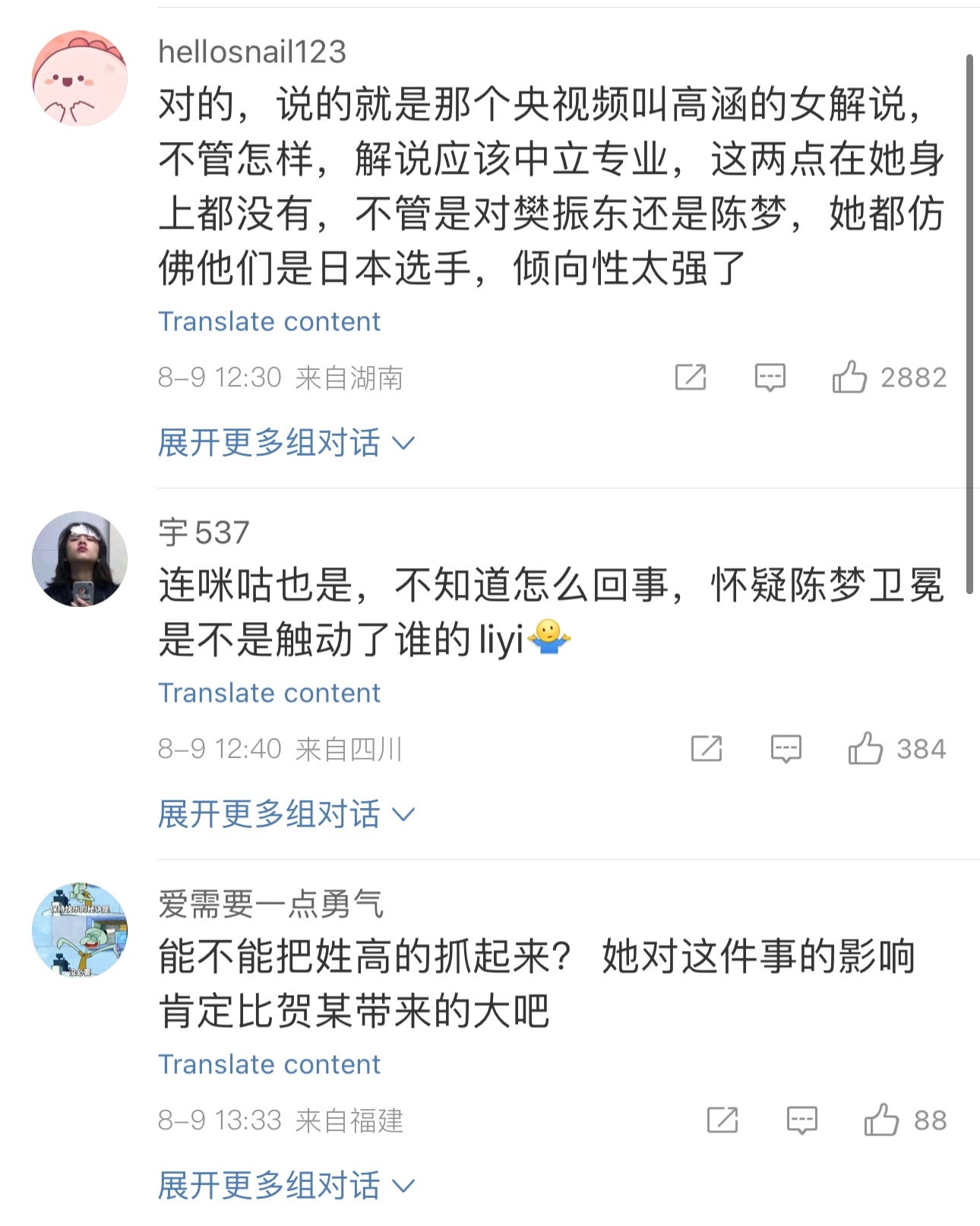

Fans of Chen, as well as bystanders at the match who noticed the bias, took to social media to protest, as celebrity fans would. CCTV’s broadcasters were also accused of preferential treatment when narrating the game, praising Sun and bashing Chen despite the results of the match. Chen’s success barely made the headlines, they said.

Later as the conflict escalated, Sun’s fans suspected that she had been ordered to retain a few tricks in her sleeve and deliberately weaken her performance, so that foreign competitors wouldn’t realise her full potential and one-up her in the next game. It is rigged from the inside, they said. The National Table Tennis team coaches and other sports authorities were then targeted in their awareness-raising.

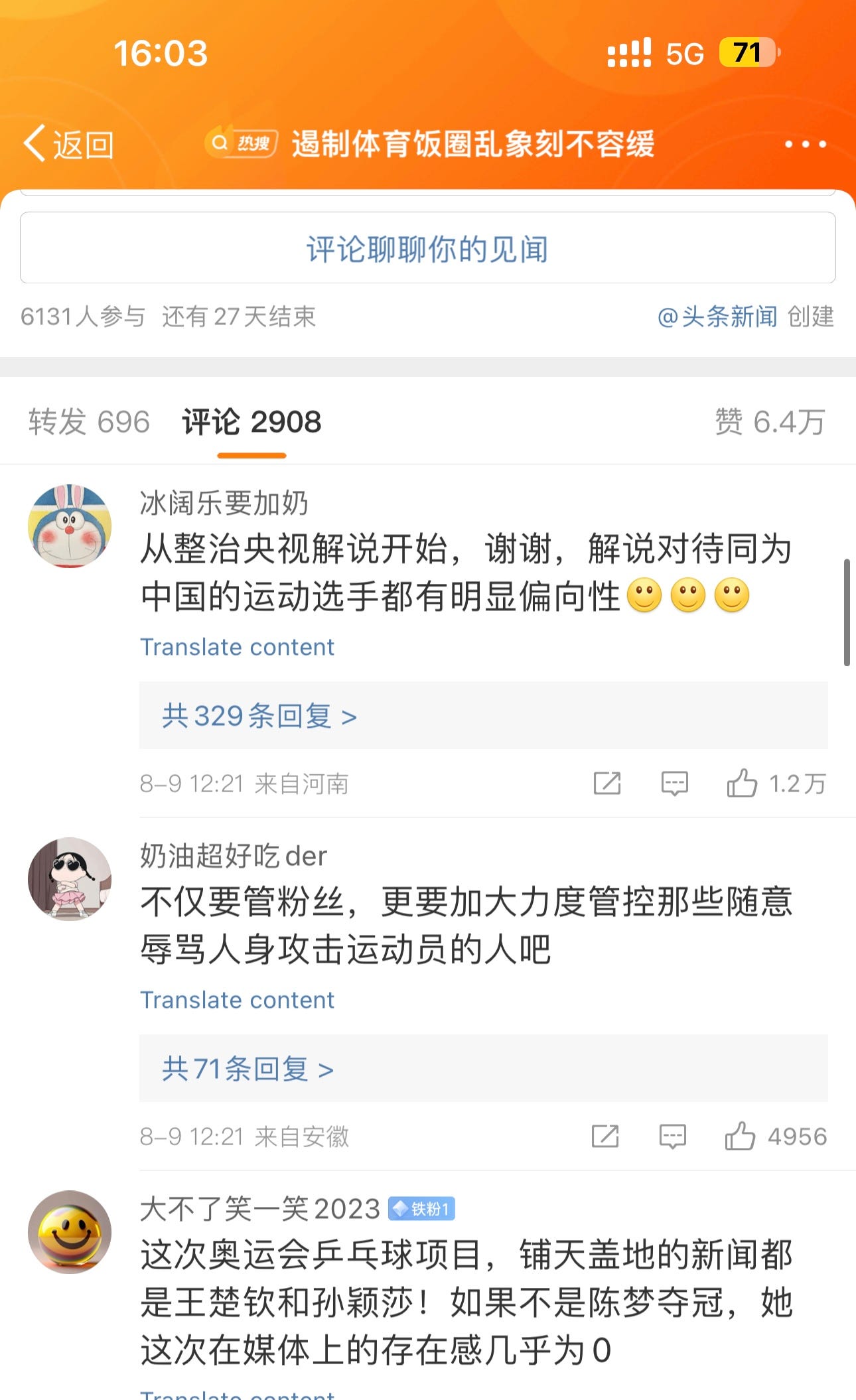

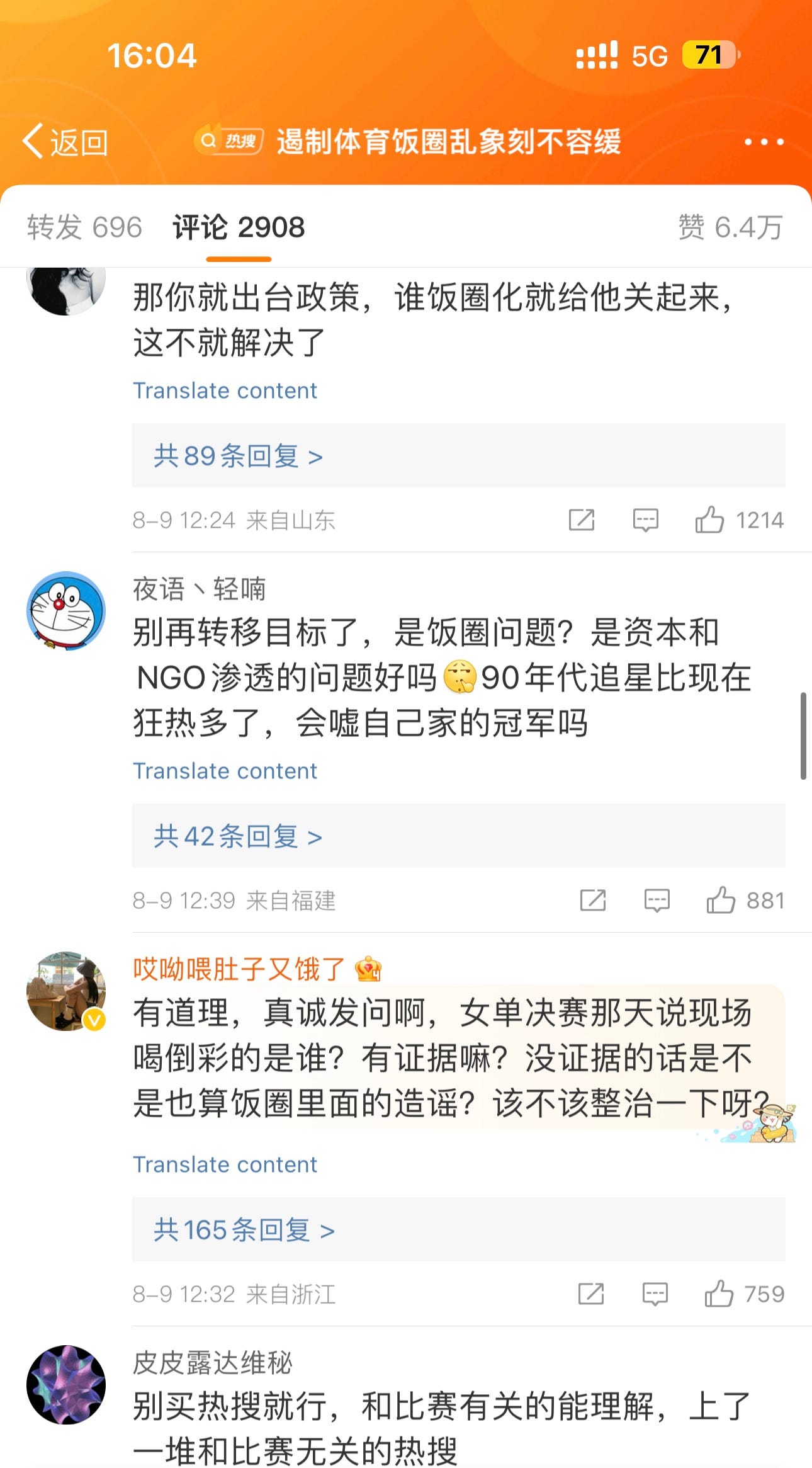

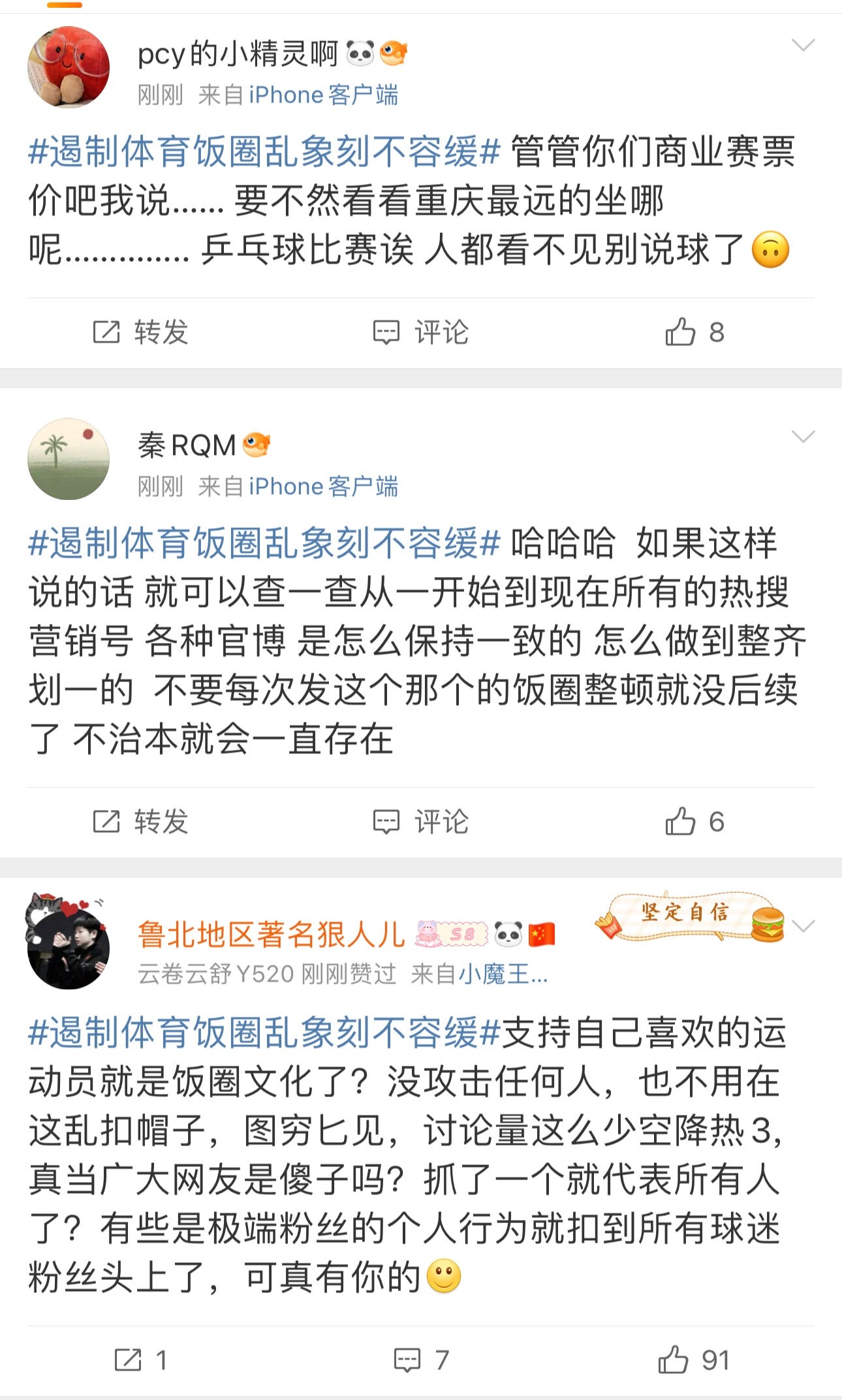

When the usual whip-cracking arrived in the form of a Beijing Daily’s commentary entitled “extermination of sports fanquan’s chaos should be immediate” (遏制体育饭圈乱象刻不容缓), these questions were asked in rage: why don’t you start with exterminating biased CCTV reporters? Or official media outlets that are blatantly churning out positive window-dressing pieces for Sun and not Chen?

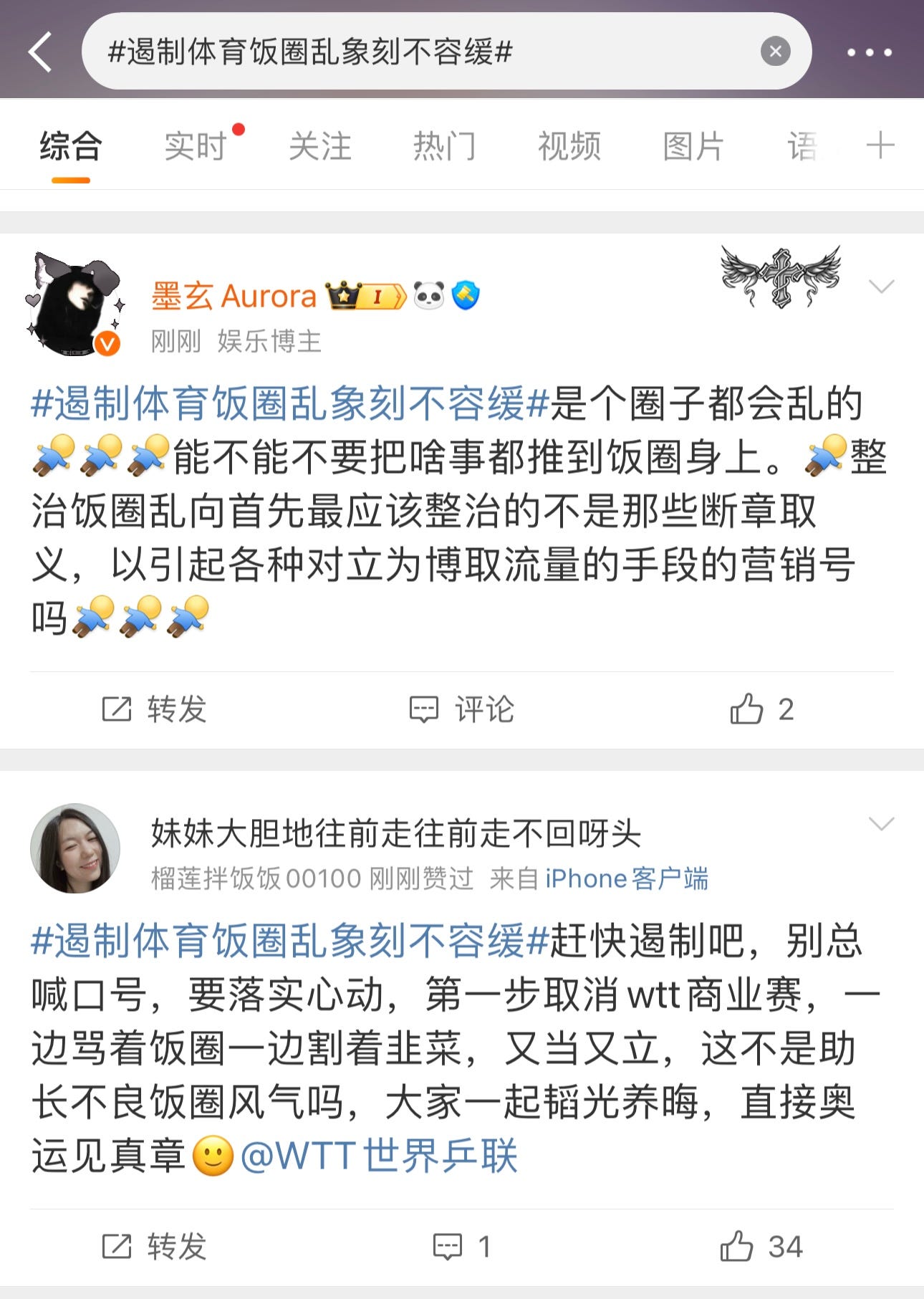

Other table tennis fans (from both sides) extended the counterattack to address bigger issues: what’s up with the new World Table Tennis (WTT) matches if you hate fanquan so much? These commercial matches (商业赛) with sky-high audience ticket prices but meagre bonuses for the athletes are clearly created to exploit the fans. China’s head coach, Liu Guoliang, has been actively endorsing the garlic-chive-cutting and pushing his team to participate. Another branch of the argument focused on the manipulation done by the capital: who’s benefiting from the fanquan-isation of sports? How is Sun trending on Weibo every day and did she purchase those hot-searches? Why are marketing accounts (营销号) instigating the debate and fishing for engagement amidst everything else?

Some took it even further: if you’re so mad about it, how about creating some laws around fanquan like we asked since the dawn of time?

This post summarises the popular sentiment succinctly:

Which athlete doesn’t have fans? When you want people to watch the matches you leave fanquan out of the conversation. When you commercialise your athletes and heighten their business value you leave fanquan out of the conversation. When you want traffic and views you’re constantly promoting them [like celebrities], and once fans accumulate you criticise fanquan-isation. Why are you being hypocritical?

I have to tap the sign and reinstate AF’s core hypothesis again: Chinese fans make powerfully insurgent claims even in a “trivial” context. When it comes to sports fans, they’re going straight for state entities like the CCTV because of the athletes’ unique entanglement with the party, and the construct of our nation.

As far as I observed, the whip-cracking died down afterwards. Two days later, de Gaulle airport spotting of the table tennis team trended as they boarded the flight home. The media heralded them as heroes again. Fans waiting at the airport were described as a sign of their “roof-exploding popularity”.

They needed fanquan and hated every second of needing it.