12. The Game is Changing

Idea Dump at the Half-Year Mark

Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

As I felt myself sweating in a rare heatwave at the Eras Tour last weekend, I realised a half-yearly idea dump issue is due.

Here are some unfinished thoughts that have been rusting away in my draft box, but they deserve to see the light of day. Enjoy these bits and bobs.

The Actress Yang Mi has recently written an academic paper on the “creative practices of Chinese actors in television series”, using her own role in “In the Name of the Brother” (哈尔滨一九四四), rated 6.3/10 on Douban, as a case study. That’s a pretty low score. However, her paper was published as a part of the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI), one of the top 3 most credible and prestigious academic journals in China.

Fanquan, especially those in higher education who are climbing the academic ladder, have been astounded by this “shameless” marketing of her pseudo-intellectual prowess. It is almost without a doubt disingenuous work that Yang did not write. Moreover, it is a slap in the face for Chinese university students and researchers who are all striving for such a “C刊” (CSSCI) inclusion that could make or break their education or career. Yang probably got there with her ghostwriter, industry network and resources without pausing for breath.

A netizen asks a poignant question: why are celebrities coming for our jobs?

First, the bianzhi and civil servant craze. Now, academic publications and PhD applications. Although the bookish smartie, the well-read poet laureate or the Study King (学霸) persona has always been popular among neiyu celebrities, it caught a new momentum in the past few years. Part of it is driven by the need to appear “authentic” and humanlike, to acquire relatability as appeal. Oversaturation is another. Every other kind of persona - the suave finance bro, the ethereal goddess - risks becoming cliches. On the other hand, there’s also the necessity of alignment and conformity: celebrities are entering academia and securing qualifications to appear upright and seek approval from above. The “positive energy spreading role model” persona is a protective safety net in case of a crackdown. Billionaires turning towards diplomas and civil service is something you wouldn’t necessarily see elsewhere.

I’ve mentioned earlier this year that narrative shorts, 短剧, will probably flatten and restructure the platforms in tremendous ways in 2024. Turns out it did. The fictional story of “王妈”, a housekeeper working for a CEO aired its first episode on Douyin in March, where it then became a series that attracted over 3 million fans in a few months. The amateur actor cast surged into instant fame.

Always unwillingly swooped into the melodrama of the CEO and his lovers, 王妈 is heralded as a “打工人嘴替”, “mouth stunt (meaning spokesperson) for the 9 to 5 office slave” with her rants in ridiculously cringy situations as well as snarky comebacks at her demanding boss.

Then, someone blew the whistle that the company behind the shorts series actually mistreats their actors by having a 6-day working week, suspiciously below-minimum-wage salary and so on. Fans of the series took to Weibo to protest because they saw the fat irony. How can 王妈, a representative of the common, a beacon of hope and a voice of the underclass fall victim to the crime she rebels against? The company ended up apologising and modifying their policies. Just like the frustration at Yang Mi’s journal entry, this popular rage for 王妈’s toxic workplace shows an entrenched dissatisfaction with the viewers’ own reality, that their jobs are incompatible with a healthy, happy life.

This also indicates a wider pattern of what I’m calling “pan-celebrification” for now: influencers and fictional internet characters entering the sphere of traditional media & entertainment. On any given day nowadays, entertainment-related Weibo hot searches would have at least 3 to 5 entries that are about Douyin, Kuaishou or Bilibili personalities breaking up, getting married, “spilling tea” or stirring up “beef”. In those hashtags, fanquan is almost constantly asking “Who is that?”. And this is not unique to neiyu. If you’re chronically online like I am, you’d know about Paloma Diamond or Nara Smith’s hold on TikTok.

For now, these personalities operate in enclaves and are considered less mainstream. When I took an influencer friend to watch Phantom of the Opera at the West End last week, she spotted a gay couple popular on Xiaohongshu in the audience that I’d never seen or heard of. They posed in front of His Majesty’s Theatre’s gorgeous low ceilings and tarnished gold interiors for the entire interval. A minute later, a group of Chinese girls behind us exchanged a few whispers: “I recognised him because I just watched his vlogs!”

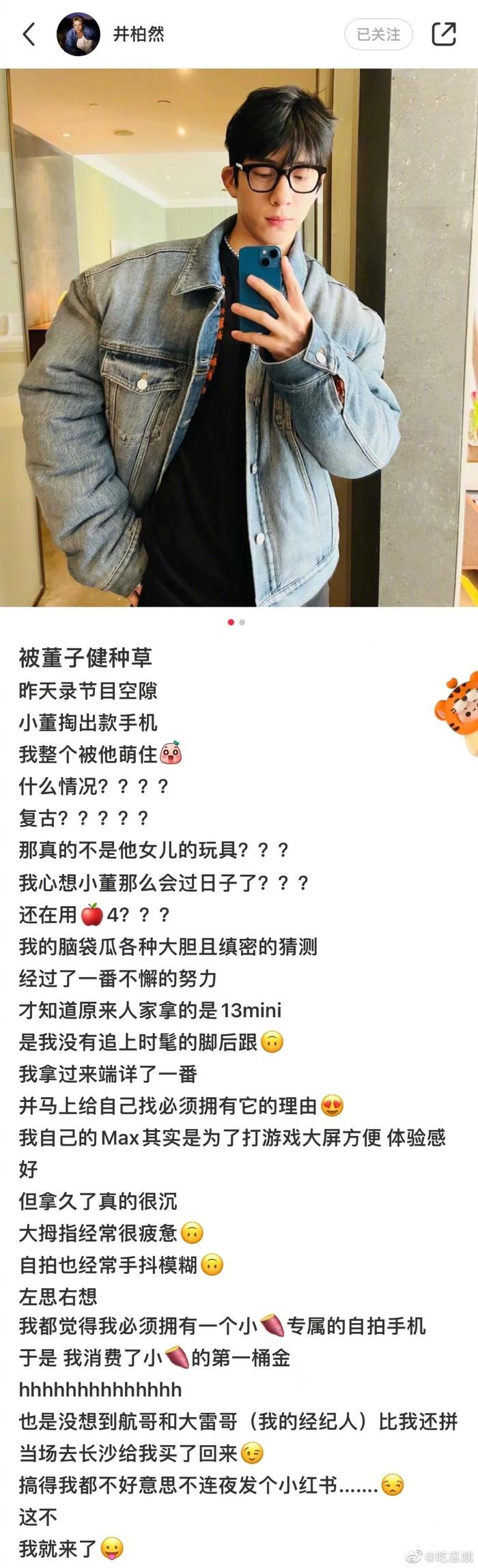

The wider implication (because there always is one) is a sense of competition and infringement for traditional celebrities. You can already see them scrambling to catch up with the more grassroots internet figures and “sinking” to their level: Bai Jingting shooting travel vlogs, or Jing Boran posting life hacks on Xiaohongshu like a regular influencer. Anyone can soar to 5 minutes of fame or even 30 minutes of a viral video, so nothing makes anyone an irreplaceable star anymore.

My thinking is that the two worlds will eventually collapse onto each other, if it is not already happening. I’m sensing among the people a hostility towards everything that props traditional celebrities up on the pedestal: glamour and beauty that feels plasticky, traffic and hype that screams superficiality, disingenuous emotional appeal that is essentially capitalist. We’ll end up worshipping someone as far away from the stars as possible. Someone like 王妈.

On a similar note, what’s on entertainment hot searches these days can be characters from Chinese otome games (乙女游戏). Designed for female players to engage with male love interests over a plotline, the Japanese genre has been domesticated into the likes of “恋与制作人” in 2017 and “恋与深空” this year. Games are not what AF is made to discuss, but what I’ll say is this: otome characters are gaining celebrity status. The unrealistically attractive and attentive men in the plot get their own supporting fan clubs, data fans and birthday light displays on buildings at The Bund, Shanghai.

A truly cunning move of the otome makers is introducing built-in gambling, a mechanism inspired by and inspiring the entertainment industry. A user can pay for more chances to draw rare character cards that will unlock exclusive, more satisfying and racy plot lines, video clips or fake phone calls. Think photocards, fan signs raffles and Rhythm Hive.

What caught my attention a few weeks ago was a hashtag called “秦彻 dom感”, referring to a character in 恋与深空 having those dominant vibes real-life actors like Wei Daxun can have. Fans of his gush over a new update to his virtual persona like physical idols.

Again boundaries are blurred: from a fan’s perspective, what are the differences between otome characters and celebrities, if there are any? Sure, the latter you can meet in real life, but the chances are slim for many of us. Most of the time, they are all out of reach, and we can love them for free but pay to get a better service. One of the male love interests in 恋与制作人 was rumouredly modelled after Lu Han. Fans of SEVENTEEN have created interactive videos on Bilibili that allows the viewers to virtually experience a relationship with them. You’ll be able to click on different options to select various scenarios on the screen, and a matching clip will play to facilitate the Dreamgirling.

Fandom studies in 10 years time would look nothing like it is today, because our research subjects have never been more dispersed and impossible to pin down.

That’s precisely why traditional celebrities find themselves under duress and are coming up with every single possible “赛道” (racetrack, a term for a profitable image or persona as a celebrity) to hold their ground in the industry. The agricultural reality show I talked about this year is facing backlash for staging a concert with their cast in Hangzhou and selling overpriced tickets. They are calling these young idol trainees “fake farmers” who are using the concept as a stunt.

At some point down the road, the crowd might start to recoil from the industry altogether. Any kind of manufactured fame becomes repulsive. People are tired of the “208” and the “资源咖” (Resource Hogs, celebrities clearly backed by capital and getting profitable opportunities without earning it). Box office total in 2024 has hit a new low in 9 years (excluding the COVID-era) because the tickets are too expensive for such shitty productions. TV series are hitting slumps without a truly explosive talk-worthy narrative.

What happens when entertainment can’t entertain anymore?