Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

This past weekend I somehow ended up in Ely, Cambridgeshire, a Cathedral City 80 miles out of London for a world-renowned choir performance my friend dragged me to. As we strolled the quiet town and browsed a quaint antique store, I found a copy of the Star, TV & Film Annual from 1968 and this article entitled “What Makes Star Quality?”:

Relieved by the editor’s breakdown of a celebrity’s appeal which my own set of conclusions are reminiscent of, I proceeded to chew over this paragraph in particular:

One factor more…perhaps the most important…essential to star quality is a sort of mystique--a magic--a personal magnetism. Without it, the other things are meaningless. But that mystique you cannot define or analyse or explain. Maybe it’s as well you can’t. If you could, star quality would probably lose its whole fascination.

This little discovery made me question whether we ought to go back in time for quality think pieces, and that everything I could possibly say about fandom has perhaps already been said. The word captures it all: “mystique” refers to a quality of mystery, glamour and power associated with someone or something.

Today, we’re imagining a scenario where that mystique of a celebrity is stripped away completely. By imagining, I mean seeing what is already happening.

Let’s talk stalkers.

私生粉 or stalker fans, as I explained in my fandom glossary, came from a transcription of its Korean original, Saesang, which literally means “private life”. It’s pretty self-explanatory. They are private-life-obsessed fans committing various degrees of stalking and harassment when fanning a celebrity.

Definitions and categorisations of 私生 behaviours are hazy and in flux. What exactly constitutes stalking depends very much on circumstantial information, although bound by a set of established consensus. Car tailing, “跟车” or “追车”, is the act of following the celebrity’s car (sometimes with a rented minivan that more than one 私生 SplitWised for), which is a universally acknowledged fandom felony. Showing up at the airport when there are rumoured sightings is more often considered “inappropriate” and not exactly stalker-y. Repeatedly calling their phone numbers (after some illegal hacking and information acquisition) is definitely off-limits. Visiting places they frequent hoping to “偶遇” (bump into by chance) is somewhat tolerable.

Beyond the aforementioned, 私生 can also break into their homes; rummage through the rubbish bin in their hotel rooms after they check out; sneak into their company and hide in the fire escape stairwells; buy their flight details (yes, there’s a black market for it) and an adjacent seat to take photos en route; so on and so forth. You’d thought I’d mention the uncovering of secret social media burner accounts or their family members’ old Facebook posts, but those are too elementary school for modern-day stalker fans.

I hesitate to call them “fans” because it would be a gross justification for their offence. In a way that does not feed into the misogynistic cladding of fandom as deranged and hysterical, I’d describe 私生 as self-serving and disorientated. They consider their idol to be their property. Despite not being a homogenous group, they all dehumanise celebrities to different extents: a pet at best and disposable party poppers at worst, playthings that satiate. In the most extreme cases, they can exercise abusive and borderline tyrannical control over the idols. Off the top of my head, I’m thinking about the stalkers splashing water on a Produce Camp 2021 contestant, Zhang Xingte, and cussing him out in the airport as retaliation after he condemned them in a livestream.

Most notoriously, there’s a 私生 epidemic over at TF Entertainment or 时代峰峻, the company that created the TF boys and then their worryingly young juniors. Like I mentioned before, TF Entertainment manages their artists in a Fostered Idol (养成系偶像) paradigm, which is heavily dependent on fans to literally raise the trainees. That entitles the fans to helicopter-parent. They tip from paying attention to someone to surveillance and oppression over their “child” who they must supervise. 3 out of 4 of the examples I gave two paragraphs before came from TF “fans”.

Because of them, TF celebrities are by far the most vocal anti-stalking advocates in neiyu. Two 4th generation TF trainees (14-year-olds), because they were relentlessly followed and harassed by 私生, got fed up and led them straight to the police station. The whole thing was actually videoed and you can see the escalating anger of the stalkers as they ask “Where do you think you’re going right now? What are you doing?”

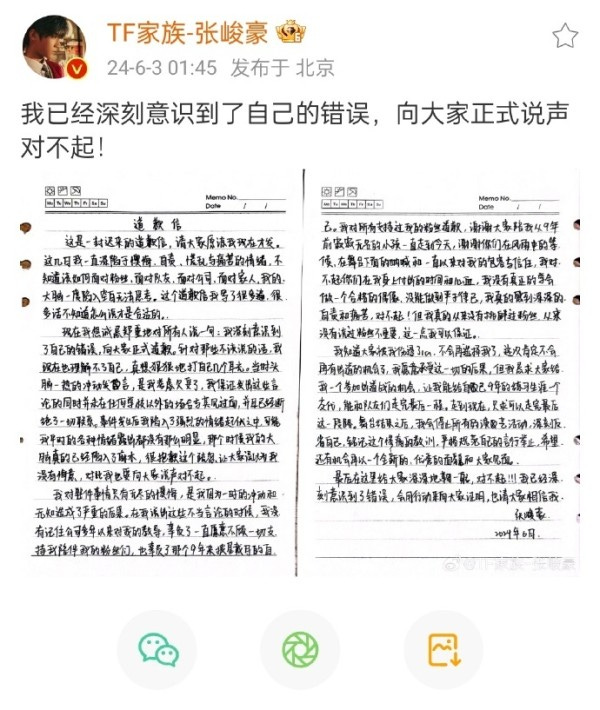

Recently Zhang Junhao, a third-generation TF trainee (after TF Boys and TNT Boys) on the cusp of his official debut, was put on trial on Weibo hot searches for allegedly dating. Fans dug up receipts of Zhang interacting with the girlfriend online, sourcing materials that stalkers procured. Criticism drowned the 16-year-old. One former fan writes: “I aced my primary school (yes I’m not joking) finals for your sake only to get such a betrayal.” Another vents “While we’re over here boosting your ranking on the debut chart, you’re chatting up a girl?”

They eventually bullied the kid into hand-writing an apology letter, stating that he had realised his mistakes and cut all ties with her. He has not disciplined himself enough and begs for forgiveness. He wants to finish one last performance in the debut battle, promising to quit the industry afterwards. The company joins the tirade and says they will seriously “lecture and educate” Zhang before pausing all of his activities after September to induce a deep reflection.

This was a bone-chilling incident to follow. It’s the fact that everyone’s in on it, playing along with it and finding no fault with it. I’m convinced again that some aspects of fanquan wouldn’t be spawned anywhere else. Only a unique blend of dynastical history, authoritarian governance, dysfunctional family values and underregulated industry could have given rise to this level of legitimised straitjacketing over an underaged celebrity's private life.

Here's where it gets complicated. A lot of 私生 of underaged celebrities, like the TF trainees, are minors themselves. It would be difficult to press charges against them, especially since laws and regulations in China have not yet caught up with these developments in entertainment (and I doubt they ever will). Are we satisfied with treating these incidents as kids messing around on the playground?

The TF model is a structural issue and I don’t want to blame it all on the fans. The “madwoman” in the minivan was not mad to begin with, but driven into it. The company allows and even encourages fans to overstep the boundaries in exchange for profits. Here’s an example: some celebrity managers would leak flight details to the official supporting fan club, who will then secretly gather available fans to “spontaneously” and “organically” fill up the airport as evidence of popularity.

At other times, they can turn a blind eye to stalkers because they can straddle two realms and exist in greyness. 私生 are very often well-respected “站姐” (fan photographers) by day, or 代拍, paparazzi by hire, a service that fans would pay thousands for. They can benefit the wider community and are not neatly reproachable. Meanwhile, stalking translates to monetary gains and traffic for both the stalkers and the company. In some very fucked up ways, everyone is benefitting from harassment.

The other side of the stalker coin is “辱追”. Short for 辱骂式追星, it literally means “verbal abuse fanning”, an extreme version of “tough love” fanning that’s sadomasochist in nature. People sometimes argue that it is but “constructive criticism”:

But the real kinds of 辱追 are not constructive. Enthusiasts habitually congregate around “toilet” accounts, a trend I’m 60% sure they started. They spout filthy insults and scathing critiques at their idols, getting a hit for being mean and therefore powerful, as well as victimised for being hopelessly infatuated with scum. They feed off of humiliation, of the self and others. Beneath it all is an avoidance of rejection, betrayal and attachment in fear of self-loath.

Not every 辱追 fan would stalk, but a lot of stalkers are into 辱追. Sometimes, they even consider themselves to be vigilantes: I stalked him and found the skeletons in his closet, like secret girlfriends that could ruin his career. I’m doing the wider fandom a favour by blowing the whistle and saving your tears. I abuse him on all of your behalf, because he has been disdainful anyway. It could also work the other way. Some 私生 would hide their house-falling scandals for them lest it mar their reputation and their fan community’s peace. Stalkers could face a moral dilemma because they know too much. To “protect” my fellow fans or my idol is the problem.

Even if we were to eradicate everyone who wants to strip celebrities bare, what we really need to ask is how much should they disclose? Should we ask them to file an annual due diligence report for fanquan to hold them accountable, since so many of them rely on fan-funding? Or else, like yet another insightful piece of Notes on K-Pop envisions, should idols unionise and strike when they feel the need to? And when they do, whose interest should they act on, the company’s, the fans’ or their own?