Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

This issue is a little different. I feel compelled to insert a trigger warning here because this won’t be a cheerful read.

While on holiday for the past week, I’ve intentionally shut my brain off, got away from social media and tuned out the background noises from my reality. I’ve let my existence dangle in the sticky trickle of time and become submerged in the inconsequential: the ocean breeze, the rustle of palm leaves like pattering rain and the tides that crash into sooty black rocks. In those moments of stillness that remain after a deliberate purging on my behalf, I was thinking about death.

All of my friends in real life would collectively face-palm reading that last sentence, because here I go again. That’s the kind of person I am, always thinking about death in one way or another. It’s been on my mind more often, because I was given so much grief to deal with this year I could barely carry it. I had to find a remote corner of the world to put it down, somewhere with rough edges and a volcanic, scorching silence that drowned my overflowing pain.

And in more ways than one, fandom has never stopped talking about death too.

Following the release of BBC’s new documentary on the Burning Sun scandal, Goo Ha Ra and Sulli’s name resurfaced. A victim and more importantly a key informant, Goo helped convict a corrupt police commissioner who was involved in the biggest sex crime in the K-Pop industry. What started out as an investigation into an assault case in the club had uncovered a putrid mess of a system rotting from the inside out, where women were brutally exploited by entertainment elites under the negligence of law enforcement authorities.

Both Goo and Sulli were young female idols in South Korea who committed suicide. Both were subjected to sexual abuse and cyber attacks. Both had long-term mental health struggles due to stress in their line of work. Both were heartbreaking additions to a still-growing list of South Korean idols who took their own lives, most notably Jonghyun from SHINEE in 2017 and most recently Moon Bin from ASTRO in 2023.

News like this shock fanquan every single time, fans of the deceased idols or not. It has devastated me every single time. I’ve written before how an idol’s death renders the entire community utterly speechless and powerless:

Imagine learning that the sufferings of your loved one were not only invisible, but also unsalvageable. That their existence had always been out of your reach, despite your believing otherwise. That you couldn’t protect them or save their lives, even if they saved yours. After the aftershocks, fans are forced to confront their mortality, and our very own. It is one hard pill to swallow, especially since modern idols intimately infuse themselves into your life as epitomes of perfection and positivity. They maintain and marketise illusions of commitment, eternal devotion and immortality. Throughout the concerts I was at last week, my idols repeatedly shouted that they would stay with me “forever”. We will be with each other forever. And for a brief second in the blinding confetti, I believed him.

An underexplored aspect of fan grief is the lack of legitimacy to grieve. We’re not the celebrity’s next of kin, childhood friends or everyday colleagues, although we are all of the above. We won’t be attending the wakes, following the hearse, dressing in black for the service knowing we are in the right place. If we do show any signs of distress, we’d get called hysterical for becoming too emotionally attached to an image, a persona.

There’s so much shaming that comes with mourning as a fan.

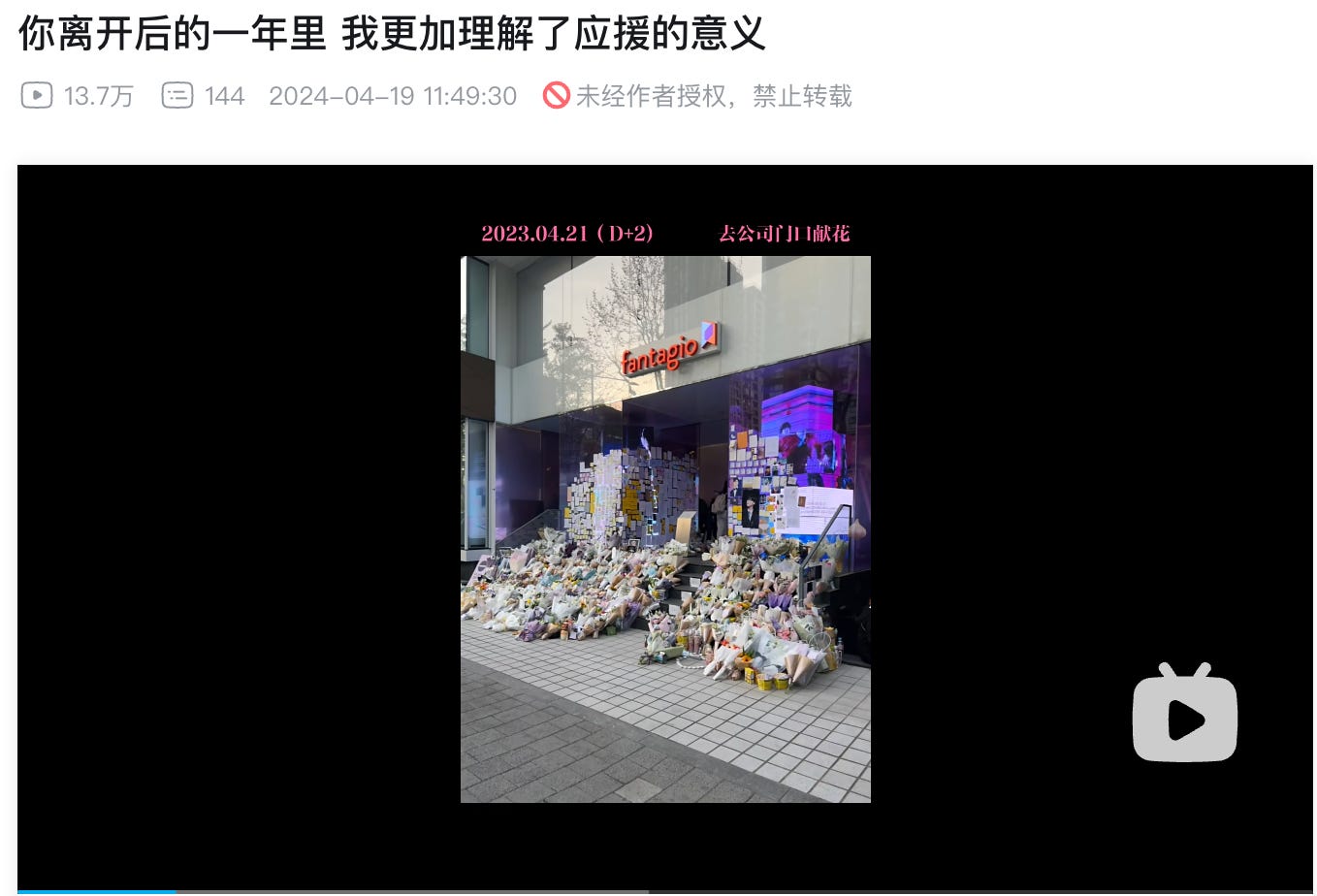

People had to find consolation in each other. Fan wars would stop and genuine empathy would ripple, because everyone can realistically see themselves in the mourners’ shoes. It could happen to all. As we do when words equally fail to convey our anger in protests, we express ourselves using symbols instead. Fans of Moon Bin, whose Korean surname “文” phonetically translates to English as “Moon”, have been using the moon to represent him. They buy his favourite drink and leave it at the doorsteps of his former management company. They host their vigils, buy bouquets made with his favourite flowers, write notes and visit his official memorial in a temple to process and cope.

The idea for this piece first came to me because of this video of a Moon Bin fan documenting her year after he passed, entitiled “understanding the true meaning of support” (你离开后的一年里 我更加理解了应援的意义).

Throughout this year, she has done everything she could to absorb the grief and remember:

The comments section houses some of the most profound discussions I’ve ever seen about death, love and fan identity. One of the top-voted comments writes:

It is not until after watching this video that I truly grasp the meaning of this lyric: the loss of a lover is not a downpour, but a lifetime of dampness.

Others write that the video has made them cry, despite not being an Aloha (fan name of ASTRO). Everyone leaves their own stories of bereavement, being a fan, a survivor. People wish their fellow fans momentary happiness in the experience of loving an idol. I learnt last week that “aloha” in Hawaiian means “breath of life”. “Ha” is the verb for breathing. To grieve your idol is to grieve something like air, the intangible and the omnipresent.

In some cases, the mourning fans are joined by his idol friends in the industry who chose to be (cryptically and explicitly) vocal about this relatively taboo subject, despite perhaps pressure from their companies to keep quiet. Members of SEVENTEEN have dedicated songs and awards to Moon Bin who they were close with. Jonghyun’s teammates in SHINEE took the initiative to continuously and openly discuss his passing, as well as encourage their fans to do the same. Gestures like these ground and settle the fandom’s grief. We’re not going mad after all.

Neiyu woke up one day in July 2023 to the announcement of Coco Lee (李玟)’s death. One of the original record-breaking divas in Mando Pop and the voice of Mulan, her sudden passing has stunned millions. It was quickly revealed that she, too, has long been plagued by depression and was mistreated by powerful players in the industry, most prominently in her capacity as the judge of The Voice of China working for Zhejiang TV. One thing led to another: whistleblower accounts of former staff and participants, leaked recordings, live audience members of The Voice coming out as eyewitnesses verifying the claims. It is suspected with substantial evidence that Coco was verbally and physically attacked as well as emotionally bullied by the producers. Even as one of the most iconic stars in Chinese entertainment ever to date, she was not immune.

Online outrage and activism gained traction. For weeks I was seeing fans from all kinds of backgrounds rally together in fury, expressing condolences, urging Coco’s family to press legal charges and demand responses from staff of The Voice. They later released a statement denying the accusations while announcing an indefinite pause on The Voice. A new round of boycotts kicked in, where fanquan brought up the age-old nickname for Zhejiang TV: 杀人台, the manslaughter channel.

The notorious broadcaster has blood to its name. In 2019 while filming an episode of “追我吧”, the then popular Canadian-Taiwanese actor Gao Yixiang suffered a fatal heart attack and died that evening. A seemingly innocuous misfortune was debunked within hours. Credible sources unveil how Zhejiang TV’s poorly designed games had rules that forced Gao into excess physical exertion. They also forced their cast to film outdoors at inhumane hours late into the night, where the temperatures were below zero, potentially causing hypothermia that contributed to the heart attack. I also remember fans on set that day alleging that Zhejiang did not call for an ambulance in time and that he passed before reaching the hospital, unlike the official statement suggested.

Both incidents have spurred on rage, and therefore unified action. I remember being appalled by Zhejiang TV’s perfunctory and shameless PR campaigns after Gao’s death and started to boycott that channel’s content until this day. I am certainly not the only one holding these grudges. It was the least I owe to those artists who were hurt.

But how far should my action go? Should I boycott neiyu altogether, because it is obviously a systemic issue since Zhejiang TV emerged out of everything unscathed? Should I boycott K-Pop and the idol industry altogether, because their entire premise is the exploitation of young talents? How can I ever consume entertainment ethically and should I try?

At the end of the day, people still ask how long does fan grief last. That question itself is a belittling of the sentiment. It implies that fan love is less than “real” love, and fan grief does not measure up to real grief. What’s the big deal in losing someone you’ve never known?

My answer to that is yes, it is absolutely a fucking big deal. No grief is too small.

Fan grief will last as long as one regrets not getting that concert ticket to see them in the flesh, who were still in possession of a beating heart. It lasts as long as one asks themselves whether they could’ve loved a little harder for it to heal those on the other end of the screen. It lasts as long as one sees another young face promising you a forever and knowing none of it can be trusted.

For now, trust is all we have.

*Cover photo: Moon Bin memorial made by fans. The photo caption reads: the moon has met the stars.