Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

On 19th April I woke up to this Weibo hot search: #霉霉一天顶BLACKPINK八年#, “One Day for Taylor Swift is 8 years for BLACKPINK”. This is a reference to how the Tortured Poet herself released a 31-track album when the entirety of BLACKPINK’s discography across their 8-year career amounts to 32 songs.

This hashtag was filled with Chinese Swifties using fanquan tactics and lingos to promote her latest work. Some post the “生图”, unedited photos of her during the Eras Tour (literally raw photos), a normalised practice to flaunt the celebrity’s natural beauty. Others enforce preventive peace-making measures with the BLACKPINK stans by saying such a comparison is unfair to both, and they’re all good singers. Another fan was a bit more aggressive: “TS rules, ‘棒子’ (a racist slur for Koreans) will lose”.

Today, let’s talk Taylor Swift in Chinese entertainment. How has she influenced fanquan?

I could begin this piece in a thousand different ways by citing jaw-dropping statistics or regurgitating articles on every single minute detail of the world’s biggest singer, but I’m opening with this:

I’ve been listening to Taylor Swift since 2008.

“Fearless” was as formative an experience for me as Jay Chou’s 依然范特西, both albums I had and still have an ancient and weathered love for. The wrinkled lyrics book to “Speak Now” is still in the glovebox of my mother’s old Mercedes, made greasy and grimy by my constant touch. The Swiftie has been one of the earliest fan identities I slipped into, the consolidation of which involved becoming an admin for a Taylor Swift fan Tieba (old-school forum owned by Baidu) and translating the lyrics of RED for others to understand. If I shuffle the Taylor Swift Complete Collection playlist I saved on Spotify with more than 400 entries, I’d jarringly leap from one mental landscape to another as my entire girlhood flashes before my eyes.

What veteran Swifties like me were a part of and helped construct was the Euroamerican Circle (欧美圈) I’ve talked about before. Communities of fans of Euroamerican celebrities had their heyday in the early 2000s, aided by platforms like Tieba and the subsequent launch of Weibo in 2009. I was active in one of the minor Tieba of TS, not the more official Tieba that people just called “大吧”, the Big One, where traffic was higher long before “traffic” as a concept was invented. Interestingly enough, “大吧” remains a term in circulation in today’s much more broadly spatialised fanquan, in reference to the most influential fan account or personae of a celebrity who’s normally a 站姐, a host of the super topic, a Lead Fan and a celebrity spokesperson all at once. That goes to show how monumental Tieba is as the OG fan discursive space in moulding the current fanquan.

It was where fans would congregate to discuss pretty much the same things as today: sighted outings, new magazine shoots, merch releases, advert appearances, new music and more. But the platform meant that fanning were a lot more localised. Back then, fanquan was a physical realm to be accessed to have hyperspecific conversations, and disappears once you shut your clunky laptop. You are bound by the forum into a cluster of enthusiasts. Those were the times. Now, fanquan is in the air you breathe - quite literally as algorithms are fed by the words you speak.

That territorial nature of those prehistoric fan spaces codified a set of fundamental beliefs and behaviour patterns that still underpin fanquan today. Firstly, the element of competition between fan clusters. With boundaries come camps. Although many normally began as casual surveyors of multiple different artists at the same time - a multistan, using today’s lingo - allegiances will eventually be pledged. You gravitate towards one or two favs. Your interest becomes walled like in an enclosure.

And Taylor Swift was not a “Diva” then. She was often criticised as a bumbling country girl who lacks refinement, an awkward and “corny” rural (“土”) singer that can’t sit at the grown-ups table. At least she was pretty to be given the less flattering and more patronising label of “小美女” (little pretty girl), but was too unlucky she repeatedly missed the Grammys by an inch. Hence the nationwide nickname “霉霉” was born, 霉 being a near-homonym with pretty but also meaning the ill-fortuned. It stuck around til this day.

In a way, she was the original underdog. I remember her being roasted by Chinese fans of Katy Perry, Rihanna, etc. for not being able to sing as maturely. “Swiftie” as an identity was embarrassing, if not shameful. Her fans felt compelled to vehemently defend her at every turn, especially her transition into pop music, her slut-shame worthy dating track record, and the Kanye West incident that ruined her reputation. She was called names besides simply the ill-fortuned, “公交车” (a bus because she was being ridden by many, if you get the innuendo here) being one of the grossest. You’d know how anger and shame are the most powerful propellants in fandom if you’ve been reading AF long enough.

That had a tremendous influence on the then-inchoate neiyu. I hope my seniority warrants this sweeping conjecture: one of the most implicit but nonetheless seminal impacts Taylor Swift had on fanquan was establishing the importance of vulnerability to success. Fans stick together when prompted to feel like they’re (alongside the celebrity) externally threatened and attacked. At the same time, she was most likely the first singer of that generation to display, weaponise and then monetise her private sufferings to such an extent. Songs about break ups, coming-of-age, and missing home dismissed relentlessly by critics evoked resonance, sympathy and more anger that led to loyalty. Honesty has a market value.

You can trace so much contemporary fanquan puppeteering back to this realisation. When lead fans, official fan club admins or even celebrities themselves want to push 散粉 (loose fans, the lay folks in a fan community) to data-f*ck or do promotions, so often their language would take on a 虐粉 tone, literally “fan-abusing”. They would exaggerate the ordeal the artist has gone through to boost morale and guilt-trip the fans into action.

I’m definitely not saying that Taylor Swift owes her popularity to playing the victim. It is one puzzle piece to her competence as well as her personal charisma. As China saw increased political suppression as well as awareness of gender disparity, her concurrent activism for the protection of musician’s wages and copyrights, women’s rights and visibility of sexual harassment in the workplace, unfair beauty standards and gender stereotypes through songs and personal lawsuits earned applause. She took on the weighty crown of a role model. Seeing a glamorous woman with attractive lovers and an accomplished career was freeing, satisfying and empowering. People view her as the heroine of a 爽文 (pleasure-fic), a specific kind of web fiction in trend these days that’s all about creating an unrealistically successful and perfect protagonist to substitute yourself into.

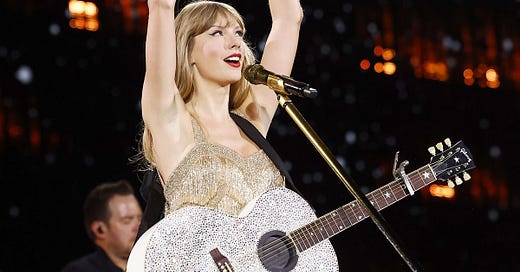

When the Eras Tour kicked off last year, there were collateral effects that went as far as an uptick in revenue for plastic beads as well as sequin dress businesses in Yiwu, China, the world’s largest wholesale market for small goods. Swifties across the globe rush to buy beads on SHEIN to braid friendship bracelets (a fandom tradition) and dress themselves in her iconic looks in preparation for the concerts. The singer also revived the vinyl industry and quite a lot of record shops that were on the brink of extinction by introducing vinyl/cassette versions of her albums. Blinken himself got a copy in China last week. Chinese Swifties went on to parade her as a powerful stimulant to the world’s post-COVID economies, while flying to Japan and Singapore to participate in those show dates.

The release of the Eras Tour movie in China had caused such a sensation that angry men took the opportunity to bash female fans as “hysterics” (what a classic) who lacked movie theatre etiquettes and disrupted public order. Female fans, not just Swifties, took to Weibo to reassert quite rightly that anti-fanquan criticism is so often misogyny in disguise. Select cinemas in Shanghai then subtly made a stand by hosting “Swiftie-only” thousand-people screenings that ensure a judgement-free sing-along experience. I’ve written before about how concerts are the brewing grounds of spatialised meaning-making. Eras Tour and the movie facilitate that crucial process.

Here’s a take that’s even wilder: Taylor Swift predates K-Pop and neiyu in terms of maintaining an intimate connection with her fans that extends beyond the production and consumption of music. She paved the way for the parasocial paradigm of the fan-celebrity relationship in modern times. In some ways, she is no different to BLACKPINK.

If you’ve been a Swiftie long enough, you’d know what I mean. She has long constructed “concepts” and themes for her albums that invites interpretations and avid discussions, layered hidden meanings into her lyrics, and hosted “secret listening parties” exclusive to some fans. Not that the genre didn’t exist in China before Taylor Swift, but she popularised autobiographical songwriting to unprecedented heights by sharing intensely personal experiences through her works. These are all maneuvres that K-Pop and neiyu have been adopting to hone in that unusually tight bond between a celebrity and the fan, except with alternative methods. Nowadays it’s livestreams, constant social media presence, reality show appearances as ways to get infinitely closer to the fan. She has even done “reverse-support” many many years ago, if you count how she appears at weddings of fans or hospital rooms for a surprise visit. That intimacy and approachability are what drive up sales and ensure fandom longevity.

I happen to agree with 三联周刊’s editorial on Taylor Swift after the Eras Tour movie accumulated over 100 million RMB of sales in China. In the piece, the editor pinpointed the crux of her global fame as “authenticity”, a sustained, unapologetic, relatable and emotionally uplifting candor that colours her entire career. I’d also argue that I had already called it when rationalising SEVENTEEN’s equally astounding triumph in neiyu in the past few years. Both had the combination of quality music, the underdog character arc, authenticity and vivacious live performances as key ingredients of success. Both gave the younger generations of today an opportunity to “发疯” (be unhinged, mad) and let loose under growing pressure to make a living. Both made their fans feel seen, heard and loved. One of my favourite lyrics from her latest album came from the song “The Manuscript”. As she re-read the words she has written about the “years that pass like scenes of a show”, the “story isn’t mine anymore”.

And what’s being a fan about if not finding yourself in the eyes of someone you love?