05. Mount Fuji

AI song covers and the mother tongue attachment

Hi there. Welcome to Active Faults.

Sora, OpenAI’s text-to-video model became quite the talk of the town in the last few weeks on Chinese internet. Amidst the discussions, a Gong Jun fan praises him for his intellect and foresight because he expressed concerns about an AI takeover a few years ago. The dangai actor saw an episode of the censored Black Mirror and lamented over a possible demise of performative arts as a profession.

I’ve got some bad news for him. A good proportion of fanquan and shippers in particular are long desensitised to AI infusions. Sora is but a step further from what they’ve been doing for quite a while. Today, let’s talk AI idols, AI voiceovers and song covers as well as the mesh of language and identity in fanquan.

Unlike elsewhere, saying someone in entertainment looks or feels like an AI is not necessarily a compliment. For an actor it means they’re robotic, unnatural and “面瘫” i.e. so expressionless and paralysed while depicting a character. For an idol, it sometimes means they’ve got too much work done on their face they resemble a plastic doll. This is also why AI idols, like the other half of “aespa”, are always warily received compared to real human counterparts. There’s something “off” about them, despite the reassuring premise that fake and perfect idols would never have a house-falling moment.

At least for now, most fans are still after the flesh and bones. I’ve reasserted more than once that all fandoms are essentially after the same embodiment: a broken God who’s every bit flawed like ourselves and perfect unlike ourselves. AI’s application in Chinese fanquan, in reality, is more about moulding the technology to deliver fan service otherwise unacquirable.

The simplest form of a digital tool wielded in fanquan could be the renowned ShindanMaker. This is a Japanese site that was popularised circa 2019 for “original diagnoses” and “fortune-tellings”. Creators can upload a prompt alongside a stash of words that will become randomised outputs, and the user can get an auto-generated diagnosis for whomever they want. Here’s an example of “what is your secondary gender and scent if you’re in ABO verse”. I entered my name and apparently I’d be an Omega who smells like roses, rust and baijiu. What a combo.

An even more popular use of Shindan was for it to tell “the fortunes” of your favourite ship. According to the Computer Prophets, Choi Seungcheol and Yoon Jeonghan’s lives are made of the ocean, wild roses and the first ray of the morning sun. As a couple, their futures consist of “brooding silences, disappointments, and trust that need not be uttered, but they’ve always been who they were from the very start”. If you’d read my review of this pairing and their characterisation in fanfiction, you’d know how uncannily accurate this description is.

Well-made Shindan can attract over several hundred thousand diagnoses. They are sources of inspiration. It supplements fanquan’s meaning-making by filling in the gaps in a celebrity-fan relationship and propelling imaginative leaps. Quoting one of my favourite lines from Nietzsche that captures the essence of fanning so well, “there are no facts but only interpretations”. Digitally randomised nonsense, when filtered through a fan’s interpretation, can fabricate intriguing scenarios and situations in which to place the celebrities. It satisfies a fan’s “will to power”, which is the emotional need to approach, understand and seek comfort from the Idol.

Shindan’s database would be a remarkable sight to behold, if you think about it. It would contain millions of names and potentialities. Infinite and interwoven past and unlived lives broken down into probable and improbable moments. It’d be a micro-universe. And what the Computer starts to expand on those moments out of its own initiative?

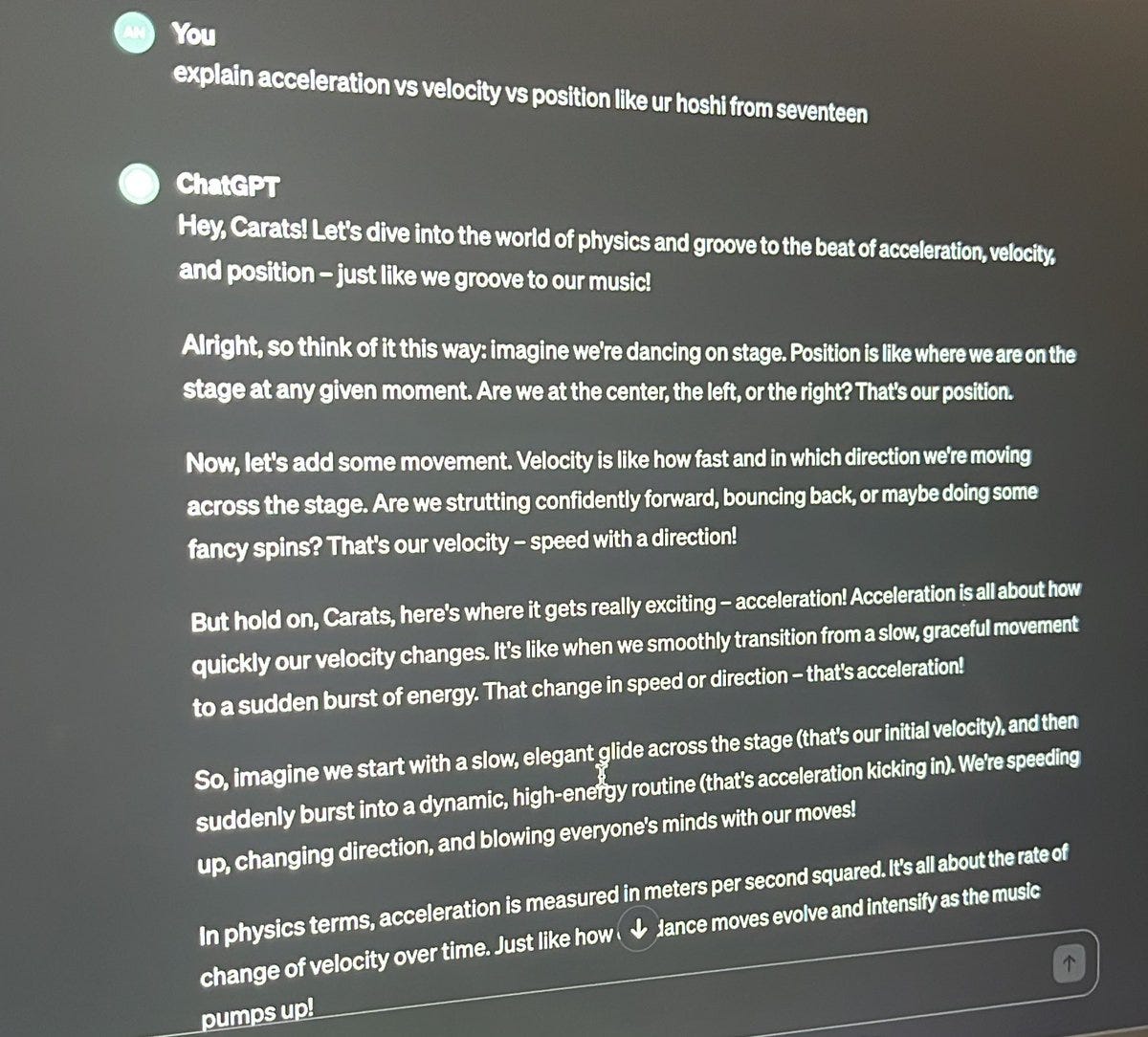

I’m reminded of a recent tweet I saw that asks ChatGPT to “explain acceleration vs. velocity vs. position like you’re HOSHI from SEVENTEEN”. The result was…disconcerting. It somehow managed to mimic the idol’s intonations, verbal habits and therefore personality quite faithfully in a foreign language that’s not even spoken by him naturally. A South Korean singer and dancer, made into an English-speaking physics teacher. Reading the response, I can almost see him vocalising it word for word without any out-of-character discrepancies. Where is it mining that data from, and what kind of source material went into the model that enabled this?

Actually, I’ve got a more pressing question to ask instead: how are fans re-making an idol through artificial intelligence?

When more HOSHI fans join the trend, use the same prompt and feed even more data into the model, will he eventually become a physics teacher to people unaware of his idol identity? Will he “cease to be” HOSHI?

When HOSHI’s group released a surprise Chinese song at their Macau concert, the top-voted comment was this: “finally a song of our own, a song to ourselves. No more reliance on AI covers!” Here’s what they meant by that.

Chinese fans of foreign artists have been using AI to get them to “sing” in Chinese. The model, allegedly an application called “Sovits” 4.0 detects, analyses and emulates the artist’s voice down to its pitch and texture, before cranking out an artificial cover that violates more than one copyright laws for sure. Think that guy who made Donald Trump sing As It Was by auto-tuning a compilation of his speech clips, but with a smarter and more efficient tool.

These covers can vary. The norm can be completely reversed and someone might want to get Zhou Shen the Chinese singer to cover a Korean song, or even Stephanie Sun to cover Jay Chou in a C-Pop Queen-King crossover. More often than not, Chinese fans create AI covers out of “母语情结”, the so-called mother tongue attachment syndrome. They want to hear the artist perform in their own language and appreciate their talent without the hindrance of a language barrier at last. I draw my examples from K-Pop yet again, simply because of the astounding prevalence of this phenomenon in that subgroup. There’s TXT’s Yeonjun covering “他不懂” or ENHYPEN’s Heesung covering “雨爱”.

As with the timeless classic “富士山下”, you’d find a cover of it created for almost every single SEVENTEEN member, where views range from just over 10k to over 210k. Comments sections are filled with fans marvelling that “this is how it feels to know what you’re singing about”. This remark under Yeonjun’s cover was particularly lethal:

I see you on a LED screen and I hear you through a synthesiser. When will I ever feel your presence for real?

The maddest “富士山下” lore I’ve seen involves a popular SEVENTEEN ship, JUN and WONWOO. The song has been a major motif in a wide-read Chinese fan fiction of the two with the same name. Eason Chan’s ballad stands on a single metaphor that Mount Fuji, symbolising an unobtainable lover, can never be selfishly owned with love. The fic took inspiration from it and wrapped up with a notoriously heartbreaking “Bad Ending” or BE, meaning the couple wound up not romantically together. The lyricism of the original song poignantly epitomises the “vibe” of their personalities, as well as the tragicality of their love story in that specific fan work.

It then inspired the creator to make an AI cover with JUN and WONWOO’s voices to commemorate a masterpiece, and it became one itself: the video is now edging towards 2 million views. Quality-wise, it can fool almost anyone because it is indeed very lifelike, conveniently helped by the fact that JUN’s hometown is in Guangdong. The knowledge that he can speak a little Cantonese in real life is a powerful nudge of the fans on their imaginative leaps. And then it gets crazier: shippers showed the AI cover to both JUN and WONWOO during fan signs, and got a positive reaction from both. As one fan commented, this is a perfectly closed loop in every sense: fan work vs. reality, the fan vs. the idol, and “my youth” that dangles in those dualities. The disappointment of a heartbreaking epilogue dissolves. An absence made complete.

Nowadays, a mandated warning attaches itself to any potentially AI-generated videos on Bilibili to alert the viewers and encourage careful distinguishment. Cover creators would often also disclaim in the description box that this is for entertainment or “memory-keeping’s sake” only, like in the case of Woo-Jun. At the same time, what you’ll find in the side panels of most AI cover videos is an ongoing series. The original uploader, considered a connoisseur and a know-how, has probably been doing this for a while under fan requests. They are basically assembling a full AI album with all the top mando and cantopop hits since the 90s, while asserting that “alterations and reposting” are strictly prohibited, as if this is an entirely original piece of artwork. Is it actually?

Are you creating “new” content when producing an AI cover for an artist?

Even prepositions become muddy here. Is it a cover of the artist? By the artist?

And what happens when, inevitably, capitalism pounces on yet another uncommodified market like this and profits begin to be extracted? Right now, Sovits seems to be available on GitHub. In the age where the AI industry is experimenting with mass vertical specialisation, will there be something (behind a paywall) specifically tailored to this demand?

“Sinocizing” celebrities through AI and other technologies is reshaping their persona altogether. It manufactures a psychological affinity between the fan and a version of the idol who’s closer, warmer, softer to the touch. The mother tongue attachment syndrome is both the cause and effect of that affinity. I can’t help but ask the implications.

Language constitutes us. The closer we get to the idol through AI, the further away we are from the real them. We’re getting Sora to do a Vlog of us at Mount Fuji.

And furthermore, do we want them to be real?

In the next issue, we’re continuing with this discussion of language and the identities of idols. A different kind of affinity can be created by deliberately exploiting the language barrier. I’m seeing this not only being done in China but elsewhere in Southeast Asia too, where fans would overlay a piece of audio in their native language on top of a K-Pop idol’s speech clips, reinterpreting the video entirely. Most of the time, it is for the purpose of creating memes and comedic effects. At other times, it is done to fulfil a sexual fantasy from the standpoint of a Dreamgirl.

See you then!

Amazing stuff.